In a darkened room, I squint to read the blurred typeface of a newspaper article that makes my stomach lurch.

It tells of a station owner who set a trap for a group of Aboriginal people by filling a cannon with powder and broken bottles and leaving it near a bullock carcass.

“When the blacks assembled for the meat he blew them to pieces with the broken glass bottles,” reads the article, published in 1905.

Making the story all the more horrifying is the fact it happened in Warwick, a country Queensland town 40 minutes from where I grew up; the place we would visit for netball carnivals or special trips to the cinema.

The newspaper clipping is one sheet of paper among thousands stacked on a platform in the centre of Archie Moore’s kith and kin – the arresting installation that saw the Bigambul-Kamilaroi artist become the first Australian to win the Golden Lion for best national participation at the Venice Biennale, in 2024. It opens in Australia for the first time at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane on Friday.

Moore, who lives in Brisbane and grew up four hours’ drive west in Tara, says he always wanted to bring the work home.

“It’s important to have it here in Queensland, where I lived all my life,” he says.

At Goma, the cavernous exhibition space housing the installation is quiet and dimly lit.

At its centre, surrounded by a pool of water reminiscent of a memorial shrine, is a platform bearing neat stacks of redacted court documents interrogating the deaths of 557 Indigenous people in police and prison custody since 1991. Equally important are the stacks of blank pages, a visual representation of the gaps where the coronial paperwork could not be found.

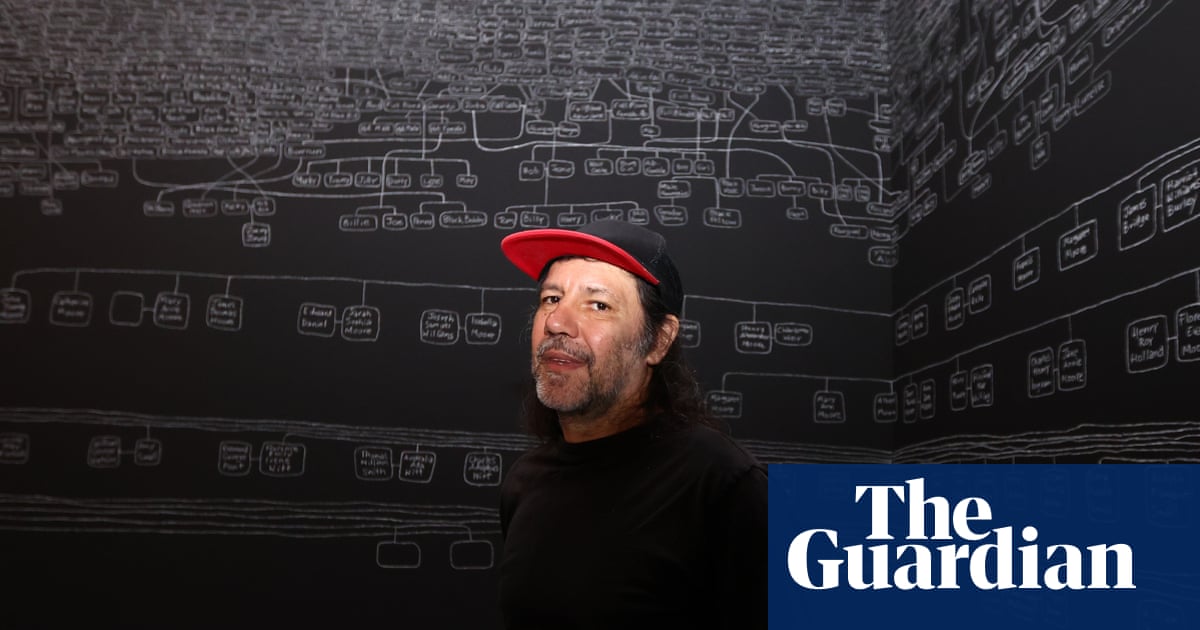

The gallery’s walls, made from blackboard, bear a constellation of names written in white chalk. What begins near the floor as a sketch of Moore’s family tree then blossoms out and upwards into the speculative realm of his ancestry, stretching 5m to the ceiling and representing 65,000 years.

While the names closer to the bottom of the tree are real, as generations pass the entries reflect the changing times – from the debasing terms favoured by anthropologists (Full Blood Male, Quadroon) to the diminutive nicknames bestowed by settlers (Black Charlie, Little Johnny) – eventually morphing into kinship terms and language words, real and imagined.

The information is drawn from years of meticulous research through state archives, libraries, pastoral diaries, conversations with family members and Guardian Australia’s Deaths Inside database.

In its new Brisbane home, kith and kin feels even more immediate. Many of the atrocities it documents happened in this corner of Queensland. As a Kamilaroi person, I recognise names from my own family, and the surnames of local footy players, on the walls.

But despite the installation’s new setting, Moore expects the crowd reaction to be much the same.

“I noticed people walking in in Venice and sort of stopping in their tracks and slowing down,” he says. “There’s quite emotional responses to the scale of the problem when it’s visualised on the table and the scale of time on the wall.”

There have been some adjustments for the new surrounds. In Venice, the installation featured a window to a canal that flowed to the Adriatic Sea and the rest of the world – “showing us how we’re connected”, Moore says. In Brisbane, sunlight beams through a high window, “bringing the sky that everyone lives under into the space”.

Recreating the work has been a challenge, but Ellie Buttrose, the curator of kith and kin, says she and Moore made a deliberate decision not to cut corners. The family tree, meticulously handwritten in chalk over two months for the Venice presentatation, was redone from scratch at Goma.

The viewer’s awareness of this labour is crucial to their experience, says Buttrose. “You know that someone has made that and it can also be rubbed away. When you’re standing in front of the work, that’s part of what’s so captivating.”

Moore is coy when asked about his history-making win in Venice. It hasn’t changed much for him, he says, apart from getting more “offers for things”.

“It’s on my CV now,” he adds.

For Buttrose, the accolade showed there was an appetite for work that invites viewers to slow down and confront “profound and difficult conversations”, at a time when museums are under increasing pressure to move towards fast-paced, colourful exhibitions that draw a crowd.

“There’s lot of pressure on museums at the moment and their funding is tied to numbers through the door,” Buttrose says.

“The huge response to this work cuts against the grain of what people think or are expecting from contemporary art museums in a digital age.”

In February, she and Moore spoke out against Creative Australia’s decision to drop Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino from representing the nation at the 61st Venice Biennale. The pair were eventually reinstated, following uproar within the art community. Buttrose says she and Moore were “thrilled” with the outcome. “I don’t think it’ll happen again.”

As Moore wanders through the Goma exhibition space, a backpack over his shoulders, he remains awestruck by the sheer scale of what he has created.

“It’s amazing,” he says. “It’s like a history painting.”

While the work is universal, it is also deeply personal.

The sprawling family tree began with a simple conversation with his mother in 2016, shortly after she’d had a stroke. She hadn’t always been forthcoming with information about her Aboriginal roots, but as her health declined, she became more open. From there, Moore began years of meticulous research, scouring the state archives and ancestry websites.

Stepping back to look at the finished product, he says the tree is a testament to his own sense of identity – a definitive answer to all the people who have ever asked him, “How Aboriginal are you?”

At its root, tens of thousands of years of genealogy begins (or ends) with a single word: Me.