Astronomers are scratching their heads after detecting a bizarre, long-lasting cosmic explosion unlike anything previously observed.

The explosion was a series of repeated outbursts of high-energy radiation, known as a gamma-ray burst. These bursts, the most powerful known explosions in the universe, typically only last for milliseconds to minutes, yet this one was observed erupting for nearly an entire day in July.

“GRBs are catastrophic events so they are expected to go off just once because the source that produced them does not survive the dramatic explosion,” Martin-Carrillo said in a statement. “This event baffled us not only because it showed repeated powerful activity but also because it seemed to be periodic, which has never [been] seen before.”

Related: ‘It gave me goosebumps’: Most powerful gamma ray burst ever detected hid a secret, scientists say

NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope first recorded the burst on July 2. Researchers then discovered that the Einstein Probe, an X-ray space telescope run by the Chinese Academy of Sciences with European partners, had detected activity from it on July 1, almost a day earlier.

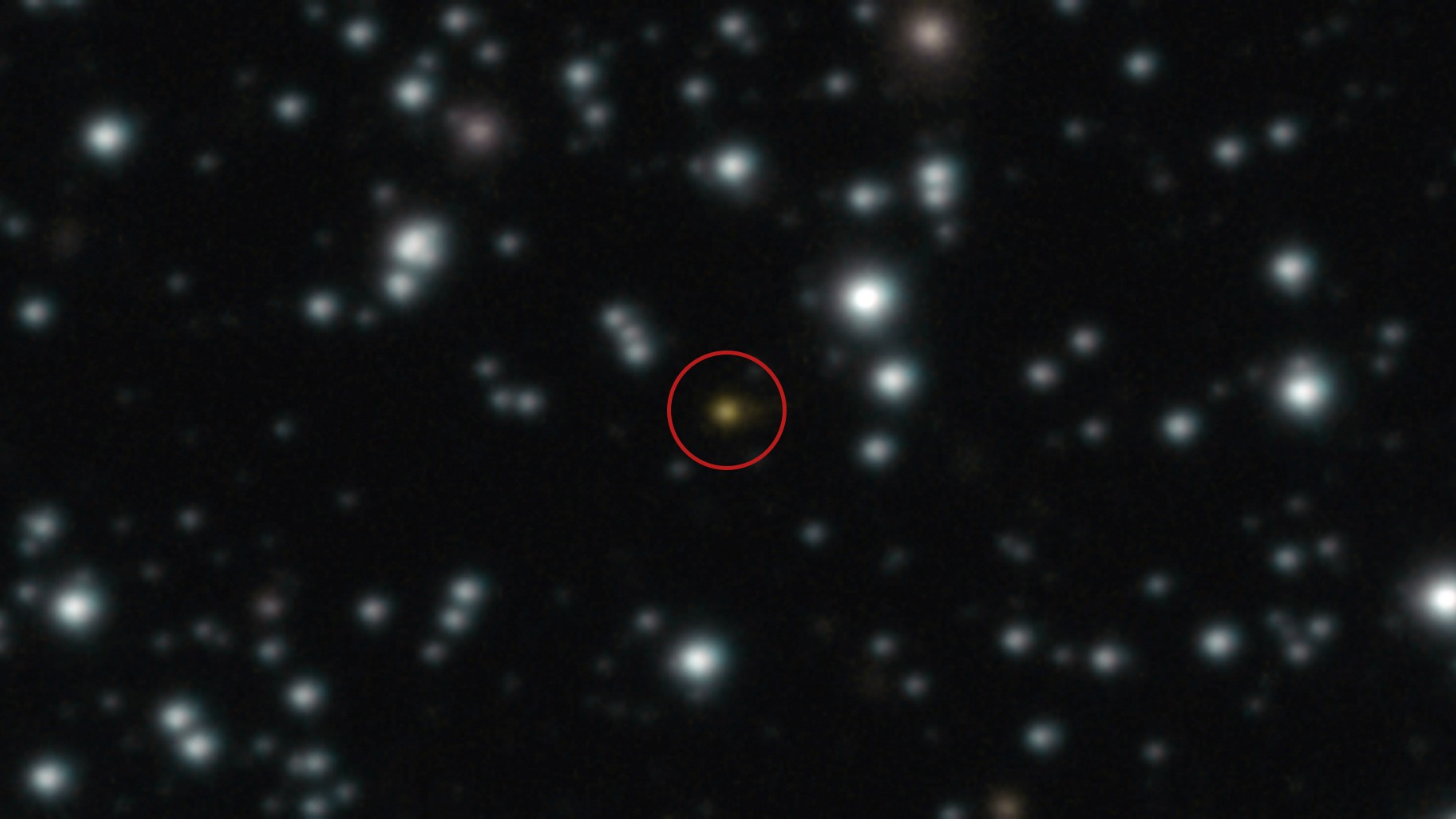

To study the burst in more detail, a team at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) turned to the Very Large Telescope, one of the world’s most advanced optical telescopes located in Chile’s Atacama desert. While originally thought to have occurred inside our galaxy, the Very Large Telescope observations suggested the strange signal had come from beyond it, an observation later confirmed by the Hubble Space Telescope, according to the study.

The study authors explored several possible explanations for the unprecedented repeated explosion.

“If a massive star – about 40 times the mass of the Sun – had died, like in typical GRBs, then it had to be a special type of death where some material kept powering the central engine,” Martin-Carrillo said.

Another possible explanation is that the radiation blasts were emitted when a star, potentially a white dwarf, was ripped apart by a black hole in what’s known as a tidal disruption event (TDE). But in order to produce the continuing explosion, this wouldn’t have been any ordinary black hole.

“Unlike more typical TDEs, to explain the properties of this explosion would require an unusual star being destroyed by an even more unusual black hole, likely the long-sought ‘intermediate mass black hole,’” Martin-Carrillo said. “Either option would be a first, making this event extremely unique.”

Intermediate-mass black holes are larger than the stellar-mass black holes (formed when massive stars collapse in on themselves) but smaller than the supermassive black holes at the center of most galaxies. Astronomers expect that stellar-mass black holes collide and merge over time to form intermediate-mass black holes, but they’ve proven incredibly difficult to locate.

The team behind the new study is monitoring the aftermath of the explosion and deciphering its cause. The next step will be determining the precise location of the explosion, which will help researchers measure how much energy it generated.

“We are still not sure what produced this or if we can ever really find out but, with this research, we have made a huge step forward towards understanding this extremely unusual and exciting object,” Martin-Carrillo said.