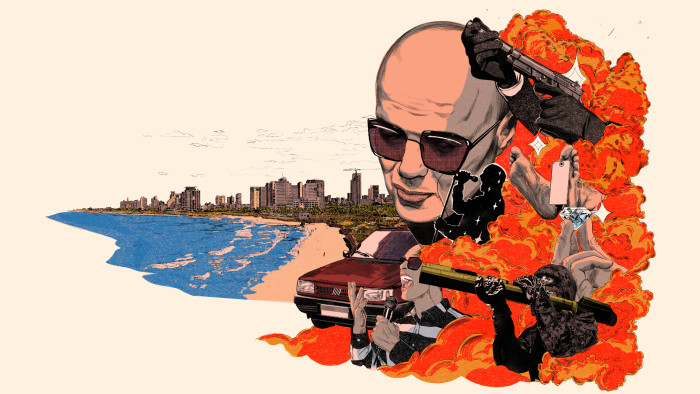

In January of 2016, Avner Harari strolled out of a Tel Aviv prison for the umpteenth time and announced he was finally going straight. The convicted assassin, who has a smooth, bald head and mischievous eyes, had spent 40 of his 61 years behind bars and had cultivated a reputation as the Israeli mafia’s “Terminator”. Now, Harari hoped that people might forget the six mobsters that police allege he whacked, as he unveiled an unlikely career change. “I was a criminal in the past,” he admitted in a television interview. “But thank God, I’m a musician now.”

Harari had spent his most recent prison term crooning songs in the Mizrahi style, a Middle-Eastern music that Israelis have adopted with the same fervour as falafel. His lilting voice was so angelic that inmates nicknamed him the Nightingale. Free from his cage after serving 37 months for firing an anti-tank missile at a rival crime boss and six years for conspiring to shoot another with a silencer, he released two tender ballads. In “A New Page” he sang: “I’m a man who pursues honesty and justice.” He hoped to perform a new album at the historic Caesarea theatre, where King Herod hosted gladiator fights 2,000 years ago, or at the modern Yad Eliyahu Arena where, more recently, Alicia Keys has performed. “I am fulfilling my dream,” he told the media.

But Harari’s record bombed. And 17 days after his release, a series of terrible explosions rocked Tel Aviv. They appeared to target those who stood in the way of Harari’s musical ambitions, including a Mizrahi music legend who refused to play his songs on her radio show. Tel Aviv police launched an investigation to discover if the Terminator was back and, if so, how far would he go in pursuit of fame.

Harari grew up in the shadow of his father’s stardom. He was born in 1954 into a famous musical family that was so successful in the 1960s that his parents and eight siblings became known as Israel’s Jackson family. “All my life, the people around me are all singing,” Harari told me, during his first interview with a western journalist.

As soon as he was old enough, Harari started moonlighting as a lounge singer at underground “Oriental” nightclubs. Back then, state radio stations banned Mizrahi music because of its Arabic influences, but Harari thrilled fellow immigrants from Morocco, Iraq, Egypt and Yemen, where his own family originated. A longtime friend of Harari’s, music agent Hagi Uzan, described Mizrahi music as a “forbidden . . . dangerous genre, one that always belonged to crime and violence and not good things”. To the western ear, Mizrahi vocals might sound like the Islamic call to prayer, a ululating cry that is simultaneously euphoric and plaintive. For Uzan, Mizrahi’s duality reflected the contradictions of Israeli life: depression and exultation, scandal and festival, all channelled through a sound he describes as “sex, drugs and trilling notes”.

Harari treated his golden voice like an instrument: “I have never smoked cigarettes in my life,” he said. He started to wear extravagant costumes and performed his own songs between crowd-pleasing covers. It was a good livelihood until 1973, when the Yom Kippur war broke out. Aged 19, he found himself in a foxhole in the Suez Canal fighting for the Israel army’s artillery corps. The war ended after 19 days, but a foolish mistake derailed Harari’s return to the stage.

“Just for fun,” he said, he liberated an American Plymouth Valiant car from the Israeli army headquarters in central Tel Aviv and took a friend on a joyride. “I got into trouble and went to prison. I sat there for minor offences, but that’s how I got to know families. Big crime families. I developed connections there. They saw that I am a reliable person who can be trusted in everything,” he told me.

In the late 1970s, Harari became a wheelman for a robbery crew that targeted Arab gem dealers outside West Bank jewellery stores. “We’d block them [with our car], get out with submachine guns . . . like in the movies,” Harari later told People, an Israeli television show. He knew only one Arabic phrase: “I will shoot you!” The “Uno gang”, so called for their puttering Fiat Uno getaway car, followed a strict code. “We were diamond robbers, but not against poor people,” he told me. “When I robbed businessmen, I felt like Robin Hood, taking from the rich for the poor,” he once told Mako, an Israeli news site, adding: “I was young. I thought I was Al Capone. I was on top of the world. I had money like water. Instead of investing in music, I invested everything in the world of crime.”

A 1980s organised-crime boom pulled Harari deeper into the underworld. Avi Davidovich, the former deputy head of Lahav 433 (Israel’s equivalent of the FBI’s Criminal Investigative Division), told Ynet News: “If there was a criminal decade, with the highest crime rate, it was this decade.” Harari told me: “You become bolder, and you want to do more and more, without stopping.” Inevitably, he started to get arrested. In 1981, when he was 27, he was sentenced to five years for driving in a robbery, wasting his prime years as an entertainer. Authorities also revoked his driver’s licence to prevent him from returning to getaway work. “I regret what I did. I did it because of immaturity,” he told Hadashot, an Israeli newspaper. “The prison sentence I received was justified.”

Harari found God and had his sentence reduced by a third for good behaviour. Like many Israeli prisoners, he was granted furloughs and even got married during this time, with Zohar Argov, the “king of Mizrahi music”, performing at the wedding ceremony. He had three children: Itay, Sagi and Inbal, whom he begged not to follow in his criminal footsteps. “Since they were little, I bought them musical instruments to have at home. I paid for courses, studies, everything. I invested in them the best of the best,” Harari told me. He led by example. After his 1986 release from prison, he became a full-time singer.

Around that time, Harari released his first album with the double title My Soul’s Desire/Man’s Destiny. Bootleg cassette recordings had made Mizrahi accessible to wider audiences, and Harari promoted his own tape with a gruelling nightclub tour, often speeding from one venue to another late at night. Harari’s friend Uzan described these venues as “Godless and lawless”. The delightfully acerbic Uzan is the kind of close friend who tells Harari uncomfortable truths about his talents: “It’s like a guy who goes to lots of restaurants, so he knows what’s tasty,” Uzan told me. “But he doesn’t really know how to cook.”

Uzan said that Harari’s music career “didn’t really go anywhere” because “his life got complicated and he turned into what he turned into”, a criminal. The police wouldn’t leave Harari alone. After nine months of freedom, he was arrested for driving without a licence and sentenced to 46 months in prison. In October 1988, he performed a farewell show at Club No. 1 in Netanya. After a standing ovation, he surrendered himself to Maasiyahu prison, swapping the $4,000 sequinned silver suit he was wearing for prison blues.

Desperate to go straight, he took a prison hairdressing course arranged by the Ministry of Labor. “I received a first-grade certificate,” he boasted. After his release, he was seen giving cuts and colours at a salon in Ramat Gan, a Tel Aviv suburb renowned for its diamond district, where he had once pulled off daring heists. His customers loved him, he said. “Women, men. I am a champion. I have golden hands.” But hairdressing couldn’t support his family and a music career. Lured by the easy hours and money, Harari returned to crime. “One goes to work in the office, I go to rob,” Harari told NRG, an Israeli news site.

There was no shortage of work. Organised crime in Israel was becoming a $14bn industry, according to Mako, with half a dozen crime families engaged in a violent turf war. It was hard to tell whether bombings and missile attacks were the work of mobsters or terrorists, and overworked security forces left gangsters largely untroubled. Harari joined the Abergil crime family, who reportedly rank among the top 40 drug distribution networks serving the US market. “I was part of their family,” Harari told me. “The most powerful family in Israel.” Media reports called him the gang’s “operational manager” in its war against the rival Abutbul crime syndicate.

Harari applied what he’d learnt in show business to criminality. He became a relentless self-promoter, built a brand and wrote his own headlines. “When you’re in the underworld, you have to be the best of the best,” he once told a reporter. “Leave no dust or anything, leave no evidence. Leave nothing.” The press started to call him the Missile Man because of his trademark weapon, the M72 LAW, an olive-coloured missile launcher. Harari preferred its lightness and its retractable viewfinder. He once explained: “It pops up, and then you let loose.” Ka-boom.

Inwardly, Harari lived two feuding personas, the tender vocalist and the ruthless hitman, the Nightingale and the Terminator. “Music is the language of angels. It’s part of my soul,” he said. “In the end, I was caught and went to prison several times. Each time, I was released for a maximum of a year and a half, and I went back to prison again.” The 1990s became a relentless cycle of music and violence, crime and punishment. By then, Harari had become “very dominant and influential”, according to his friend, Uzan. When Uzan gossiped about Harari on his radio show, Harari lit up the switchboard and demanded a retraction.

Then, in May 2000, Harari was arrested near the scene of a motorcycle assassination with gunpowder residue on his clothing. This time he was sentenced to a partial house arrest for six and a half years. “From 10 o’clock at night, you are not allowed to leave the house,” he explained. For other gangsters, this would be a slap on the wrist, but it crippled Harari’s music career. The clubs only came alive at 11pm.

In late December 2005, one of Harari’s preferred M72 rockets narrowly missed crime boss Assi Abutbul outside his Netanya beach home. Harari was convicted of orchestrating the failed hit and sentenced to 37 months, despite Abutbul claiming during testimony he remembered nothing about the attack. (Israeli underworld figures have famously foggy memories, even when quizzed about their enemies.) The police charged Harari with six other gangland murders, but those he denied. “In all six cases there was nothing,” he told People. Not long into his sentence, Harari’s motorcycle assassination case collapsed due to weak evidence. He was exonerated and awarded nearly $25,000 in compensation.

Freedom did not last long. In January 2009, Harari bumped into a rival crime boss at a Tel Aviv BMW dealership. Shalom “the Black” Domrani, whose loan-sharking operation allegedly continued despite the police surveillance balloon permanently hovering above his home, set his goons on Harari. They broke his nose and ribs. During a police interrogation, Harari described his rival as “human scum” and warned: “He will be in a black bag, that’s a promise.” Domrani was convicted of causing grievous bodily harm and, for his threats, Harari was thrown back in prison for 10 months.

“After each prison term, I swore I would never return, and here I am,” he said later. “It bothers me that I missed the development of my children. They grew up without me. I wasn’t at the eldest son’s graduation party, and I also missed his military discharge party.” By then, Harari’s son Itay was in his twenties and had become a professional Mizrahi singer. Itay begged his father to stay out of prison, the same advice his father had once given him. “More than he protected me, I protected him,” Itay told People. (He declined to speak to the Financial Times.) His father didn’t listen.

In 2010, police listening to a wiretap overheard Harari plotting to kill a rival gangster. Officers arrested him near the man’s house and discovered a gun with a silencer stashed nearby. Despite his “remarkable persuasiveness and personal charm”, a judge convicted Harari of conspiracy to murder, sending him to prison for six more years.

This time Harari decided to reinvent himself as a tech mogul. In 2013, he tried to launch an iPhone app to help patients navigate Israel’s complicated hospital system — from his jail cell. The Jerusalem Post questioned if it might help “would-be hit men find their wounded quarry in the hospital in order to finish them off”.

Yet each new personal reinvention was like an audition for a life he never wanted — soldier, assassin, hairdresser. Only when he sang did he feel like himself. During his prison furloughs, Harari performed at weddings and other events. “People would get up specially to take selfies with me, asking me to take more photos than the groom! I’m like the star of the evening. I sometimes feel embarrassed by it,” he recalled. By 2016, digital streaming had finally propelled Mizrahi music into Israel’s mainstream, as artists blended traditional Middle Eastern sounds with EDM, pop and hip-hop. Harari’s music was having a moment. Aged 61 and nearing the end of his prison term, he realised this might be his chance to top the charts.

The question was whether the public could embrace a performer who was part Frank Sinatra and part Richard Kuklinski. Not long after he was released, Harari invited a crew from the Israeli television show People into his gaudy “pleasure house” in Savyon, Israel’s Beverly Hills. The presenter said that the mansion was the type of house that you only see “in Mafia movies”. Harari admitted that Pablo Escobar inspired the interior design, but insisted his wealth came from a large inheritance and a grocery store he owned. He said that he was also working as a borer, an unofficial mediator who resolves conflicts between warring crime families. Soon his home filled with photographers, agents and publicists, hired to promote his album of original songs and covers. His son Itay sang for the cameras: “The nights are long since the day you left.”

In the album’s sleeve notes, Harari wrote: “I really don’t care if they don’t play me on Galgalatz,” referring to Israel’s military-run music radio station and its official pop charts. But by the paragraph’s end, his vulnerability crept in: “But with God’s help, my hits will be played a lot on the radio stations.” He dedicated the record to those who were self-made “with five fingers”, a coded reference to fellow thieves that he hoped would give his record a streetwise edge.

Harari had grievously overestimated his chances. Israel’s charts were dominated by artists with millions of YouTube followers, who promoted their songs on Instagram, something Harari knew little about. “I’m not sure he knew how to release [an album] . . . in terms of how things work these days,” Uzan told me. “He even released a CD album. Like an actual hard copy disc!” Uzan said that Harari was shocked by the poor reception and felt disrespected. Police alleged that, fuelled by his failure, Harari resumed his role as an underworld hitman, targeting people who had rejected or crossed him, and to earn money to fund his music career.

On December 19 2016, businessman Meir Shamir thought he heard fireworks outside his northern Tel Aviv home. He discovered shrapnel and circuit boards. Eleven days earlier his BMW had also mysteriously exploded. “The second time I realised it wasn’t a mistake,” he said. Someone was trying to kill him. Shamir had recently been involved in a business deal that turned sour. He alleged that mobsters who claimed affiliation with the Abergil gang had demanded more than $4mn. Police immediately suspected the group’s explosives expert, Avner Harari, of planting the bombs, which they said had the power to kill.

At the end of 2016, detectives recorded coded conversations between Harari and an employee at his grocery store, Avishai Ben David. Despite Ben David’s master’s degree and clean record, he appeared to be planning something sinister.

As Harari struggled with rejection, he began telephoning radio stations directly. In January 2017, he reached Margalit Tzan’ani, then 68, who is the Madonna of Mizrahi music, and a DJ at Radio Lev Hamedinah. “Margol, I have songs, I made beautiful songs, listen to them,” he pleaded.

Their accounts of the conversation differ dramatically. Harari claimed she promised him airtime; Tzan’ani insisted she fobbed him off on her producer. When his songs remained unplayed, Harari’s humiliation curdled into rage. Not long after that, Tzan’ani was startled to find the former hitman waiting for her in the studio, wanting a word. Uzan speculated that Tzan’ani gave Harari the bad news about his record, “and maybe he didn’t like hearing it”.

A few days later, an explosion lifted Tzan’ani’s silver Buick off the ground in a parking lot. Her producer received a text message that read: “If Margalit continues to come to the radio, we will make her and all the employees food for crows!”

Tzan’ani is no angel. She was convicted in 2011 of hiring gangsters to blackmail a music promoter, and she appeared to be suffering from a foggy memory when reporters asked about the car bomb. “Give me a break,” she sighed, eventually blaming the explosion on engine problems. (Tzan’ani declined an interview request.)

Yet, Harari made cryptic statements that seemed to hint at knowledge of what happened: “She forgot where she came from,” he told Israel’s Channel 1. “So apparently someone in the field or industry decided that he needed to wake her up a bit.”

Harari suspected undercover detectives were spying on him at his grocery store, posing as customers. He could spot a police officer by their shoes, he said. “According to the police, the vegetable shop is just a camouflage, it is the base for going to battle,” said longtime Israeli crime reporter Buki Nae. Police wiretaps recorded Harari planning something involving “strawberries” that they believed was a plot to bomb a football player named Kobi Musa.

The Tel Aviv district police department said they watched Harari’s accomplice, Ben David, hide a bomb in the player’s car. When Musa emerged from training, officers grabbed him before he could open the door. “The explosive charge there was very large, a charge that leaves no chance for a person inside the vehicle to survive,” said crime journalist Avi Ashkenazi. The footballer was terrified. “I’m married with children. There was pressure at night. I couldn’t sleep that much,” he said.

Police arrested Harari and Ben David for attempted murder, conspiracy, weapons offences, extortion and other charges. The prosecution built their case on “strawberries” being criminal code for bombs. “We know, for example, that when criminals talk to each other that ‘iron’ is a gun,” Harari told me. “But strawberries? There is no such thing in the criminal lexicon.”

The trial gripped Israel, bringing together stars from entertainment, sports and the criminal underworld. In March 2017, the Tel Aviv District Attorney’s Office accused Harari of ordering Ben David to plant bombs to extort his victims for money. “I hung up the suit,” Harari insisted, describing his life as a mobster in the past tense. “My hands are as clean as silk, I’m being arrested for doing no wrong . . . I have two granddaughters and one more granddaughter on the way. I want to be with the family.” He moaned that he was a victim of his own fame: “The police claim that I carried out some of the family’s business,” he told me. “I paid a heavy price for it, for being with them.”

Wearing sunglasses, a nervous Tzan’ani told the court that Harari had never threatened her. She gushed that Harari’s son, Itay, was “an outstanding singer”, and in return, Harari said: “God willing I will do a duet with Margol outside. We are good friends.” As for the footballer, Harari said he didn’t even know him.

The evidence against Ben David was overwhelming. Police discovered bomb-making materials at an apartment linked to him. The court found both Ben David and Harari guilty. Harari was sentenced to 11 and a half years in Rimonim Prison, a maximum security complex north of Tel Aviv. Ben David was given 15 years. Like all prisoners in Israel, Harari was banned from giving interviews to the media. The Nightingale had been silenced.

Stewing behind bars, Harari reached out to a young Israeli soldier he knew on the outside. The soldier and his mother knew their way around computers, Harari said, and he asked them to start a social media account on his behalf. “They have software and all kinds of things,” he told me, vaguely. Harari recorded his voice on a contraband cell phone in prison and sent the file to his friends on the outside. “We started uploading it to TikTok.”

Harari’s online videos blend politics, self help and music. In 2023, he even released a statement from prison using artificial intelligence. His friends on the outside used AI to make his lips move on a photograph, creating a kind of deepfake cameo. In the clip, AI Harari advises followers on surviving police questioning and warns them not to sacrifice their dreams like he did. “In the end, crime doesn’t pay, even if you succeed,” he told me. “The universe rejects it. Man cannot afford to do things against nature.”

Harari’s honesty found an audience and his popularity rocketed, reaching more than 20,000 followers. “I see people’s reactions on TikTok, and I can’t believe it,” he told me. “Avner, we love you! I have thousands of likes, it’s crazy! I can’t figure it out. Who admires someone who is considered the number one criminal in Israel? I don’t understand it, but I say: ‘If I’m applauded, then what do I care?’”

In January 2023, Israel’s Channel 13 broadcast a special profile about prisoner number 41697. The host described Harari as an amateur singer known to all Israeli police, who is now “a TikTok star”. This got Harari thrown in solitary confinement and ordered to shut down his social media. Harari fought back on a technicality — the media ban prevents him from speaking to journalists, not to fans on social media.

Harari said that TikTok brought in unusual business opportunities. He said he’d been offered roles with a diamond-cutting company, an egg-distribution firm and even a company that made chicken coops. Some fans wanted to send him money to spend at the prison canteen. “I have money, but I say, ‘Thank you very much, everything is fine,’” he said.

The outbreak of war in Israel disrupted the reporting of this story, and Harari’s appeal for freedom. He had apparently broken prison rules to telephone me on a contraband cell phone, and complained that his tongue was sore from the heat in the prison. (He is a crusader for air conditioning in jails.) “I am a champion at talking and selling. I have these skills,” he boasted. Yet his personal life was in disarray, he admitted. “I’m broken up with my wife. I met someone new, it’s a bit problematic,” he said.

But things are looking up. Harari will soon face a parole board that could reduce his remaining sentence by a third. “In my opinion, we will not oppose his release from prison,” a Prison Service source told Mako in April. “He is a positive prisoner who has undergone . . . a rehabilitation process and participated in workshops to treat anger and acts of violence.”

For now, Harari is spending his days writing new songs and working on his voice. “I have tremendous vocal power,” he said. “As soon as I leave here, I enter the recording studio.” Now aged 70, he still believed there was time for his big hit. But like anyone pursuing a passion, he will always be torn between the star he dreams of becoming and the man he must be to make ends meet.

After our call, as dusk consumed the prison, the Nightingale awakened for an evening performance. His song, euphoric notes leavened with sadness, rose into the night sky. Followed, as always, by a polite ripple of applause.

With additional reporting by Melanie Lidman and Ilan Ben Zion

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram