A new documentary traces the life and artistry of kyōgen master and living national treasure Nomura Mansaku, capturing a landmark performance and more than 90 years on stage. Here, his grandson Yūki reflects on what it means to inherit such a profound tradition.

At 94, Nomura Mansaku remains a towering figure in the world of kyōgen. Six Faces: Kyōgen, A Life on Stage documents a single, extraordinary day—June 22, 2024—marking both the ninety-third birthday of the living national treasure and a commemorative performance celebrating his Order of Culture award.

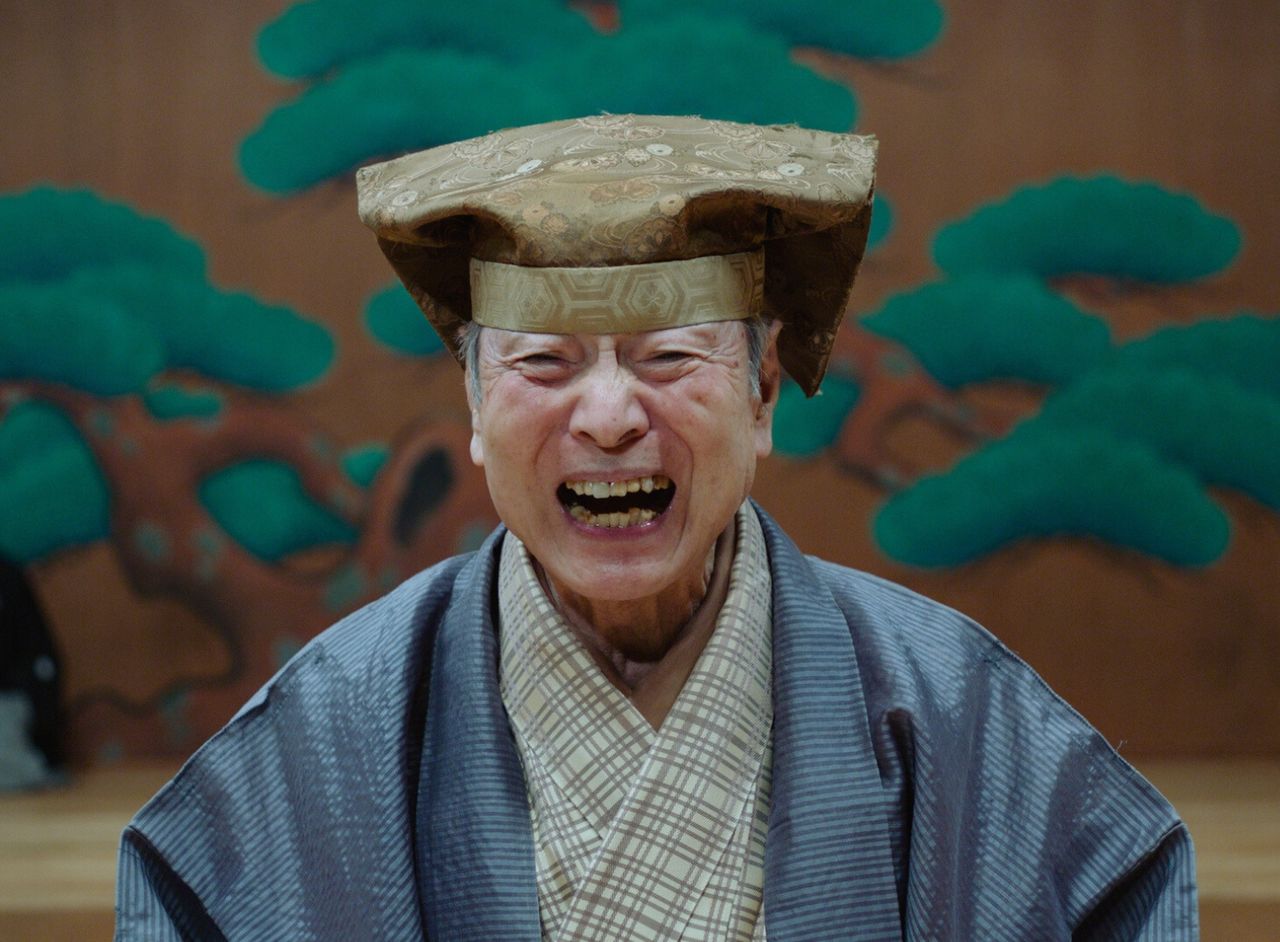

Kyōgen legend Nomura Mansaku, who turned 94 on June 22, 2025. (© Mansaku no Kai)

Director Inudō Isshin captures the immediacy and depth of Mansaku’s performance in Kawakami, a work the actor has spent a lifetime refining. Inudō also films a rare moment when Mansaku shares the stage with his son Mansai and grandson Yūki, representing three generations of kyōgen artistry. Through interviews tracing Mansaku’s life and animated sequences depicting the “six faces” that surface as he looks back over his career, the documentary offers a multifaceted portrait of a theatrical legend.

A Glimpse into His Grandfather’s Art

On the day of the film’s release, Nomura Yūki, who respectfully refers to his grandfather as “Mansaku sensei,” shared his thoughts on aspects of the documentary that made a renewed strong impression on him.

“He’s incredibly honest in his approach to the art. The sincerity with which he engages with each role, never overcomplicating things, really came through.”

(© Hanai Tomoko)

Mansaku made his stage debut in 1934 at the age of three and has continued performing through wartime and postwar Japan, sustaining a career spanning over 90 years. Even in his advanced age, his commitment to refining his art leaves Yūki in awe.

“Normally, just being able to perform onstage at 94 would be remarkable enough,” Yūki notes. “But Mansaku sensei is uncompromising in his art. He’ll hop around the stage on one foot without any effort. It amazes me that with unwavering conviction, you can transcend the limits of age and physicality.”

Moments before stepping onstage, Mansaku focuses on his role in the kagami-no-ma (mirror room). (© Mansaku no Kai)

The Weight of Generations

The Nomura family has been performing kyōgen for over 300 years, a lineage that goes back to the Edo period (1603–1868). There is a family maxim about the kyōgen path: “Begin as a monkey, end as a fox.”

One’s artistic career typically starts at the age of three in the role of a monkey in Utsubozaru, a piece about a daimyo lord trying to convince a monkey to give up its skin for his quiver. And it culminates with the technically and emotionally demanding Tsurigitsune about a hunter trying to trap a wily old fox. Only after mastering the latter are actors fully recognized for their artistry.

Yūki also made his debut at age three playing the monkey in Utsubozaru. He has more recently begun performing the daimyo role that his grandfather and father had portrayed, with the youngest children in the family taking on the monkey role.

“Finding myself in the position of offering guidance, just as my father and grandfather used to do, is a feeling that’s hard to put into words.”

(© Hanai Tomoko)

The Radiance of Each Generation

In 2018, the three generations of the Nomura family performed the same piece, Sanbasō, in Paris. Yūki says that interpreting the same work in different ways revealed more vividly what it means to inherit a performing art tradition.

Nomura Mansai, right, as the blind man’s wife in the kyōgen play Kawakami. (© Mansaku no Kai)

“There’s a beauty that can only be expressed at that particular stage in an actor’s life. We’re at different rungs on the ladder of experience, so naturally there’ll be differences in nuance and quality of expression. For the audience, I’m sure it’s fascinating to compare. But for me personally, it was a revelation to see how things are interpreted when you reach that level.”

There is more to a performance than reproducing certain movements. Artistic expression is born of differences in age, experience, and individual physicality. This insight allowed Yūki to gain a fuller awareness of where he currently stands in the continuum.

“It’s a bit like making sake—the more you polish the rice, the clearer and more fragrant the flavor. At the same time, I feel there are qualities like freshness and vitality that can be expressed most effectively at this stage in my life.”

(© Hanai Tomoko)

Kawakami and the Road Ahead

The main work featured in the documentary, Kawakami, was first performed by Mansaku at the age of 25—and he continues to perform it to this day. It depicts the love and fate of a blind man and his wife, and its melancholy tone is highly unusual for kyōgen, given the genre’s comedic reputation.

“The day may come for me to perform it myself, but it still feels far beyond me. It’s a piece that my grandfather holds so dearly that he once traveled to the village of Kawakami to perform it.”

Mansaku appearing as the blind man in Kawakami. (© Mansaku no Kai)

The solemn landscape of the temple Kongōji in Kawakami, Nara Prefecture—the setting of the kyōgen play of that name. (© Mansaku no Kai)

Yūki sees kyōgen not just as a comedic art but as a form expressing sorrow and beauty. This view, passed down from Mansaku, is part of the Nomura family’s tradition and lies at the heart of their art.

“For my grandfather, beauty comes first, and humor enters only later. During lessons, he rarely talks about the mindset we should carry. That’s why there’s so much to learn from documentaries like this and written records. In the film (in describing his artistic aspirations), Mansaku sensei shares a haiku by his father: ‘After a while / I look again / and the moon is still high in the sky.’ That really resonated with me.”

A scene from Kawakami. (© Mansaku no Kai)

A Traditional Art Form, Open to the World

Mansaku still talks of performing outside Japan—another clear sign of the Nomura family’s commitment to sharing the appeal of kyōgen with a broader audience.

“I sometimes worry whether someone his age can survive a long flight (laughs). But my grandfather has been performing kyōgen abroad for nearly 70 years.”

A scene from Kawakami. (© Mansaku no Kai)

Since staging kyōgen’s first overseas performance in France in 1957, Mansaku has brought the art to audiences around the world. This achievement represents not just the preservation of a traditional stage art but its evolution and outward transmission. For Mansaku, national borders have never been barriers.

Carrying that spirit forward, Yūki has also conducted workshops abroad to share the charms of kyōgen.

(© Hanai Tomoko)

Beyond the Stage: Sharing Kyōgen with the World

“It’s not enough to hone your art through conventional performances.” Yūki is now focused on refining and projecting his own voice.

He actively organizes his own theatrical showcases and frequently appears in the media—driven by a desire not simply to preserve kyōgen but to attract more people to it and win them over. Instrumental in shaping his desire to expand kyōgen’s horizons has been his father, Mansai. Yūki starred in a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet that his father directed and also performed in the nō/kyōgen adaptation of the popular manga series Demon Slayer.

Nomura Mansai, a kyōgen superstar in his own right, passes on what he learned from Mansaku to Yūki. (© Mansaku no Kai)

“I’m open to photos, videos, whatever it takes to bring kyōgen to a wider audience. But I have to take that first step. Otherwise, the art will stop growing.”

Getting dressed in a kyōgen costume is a task requiring three assistants. (© Mansaku no Kai)

A True National Treasure

He says he has seen the recently released, much-talked-about film Kokuhō, “National Treasure,” about an orphaned boy who becomes a kabuki legend. “I was amazed to learn that the lead actors achieved that level of artistry after only a year and a half of training.” While expressing deep respect for the actors, he calmly reflected on his role as an inheritor of a traditional performance art.

In Six Faces, Mansaku’s offstage moments are filmed in black and white. (© Mansaku no Kai)

“Artistic mastery alone doesn’t make a living national treasure. You also have to nurture the next generation, communicate your art, and leave a lasting legacy. Only then, I believe, can one truly be called a ‘treasure of the nation.’”

(© Hanai Tomoko)

Trailer (Japanese)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Kyōgen actor Nomura Yūki. © Hanai Tomoko.)