Newsletter Signup – Under Article / In Page

“*” indicates required fields

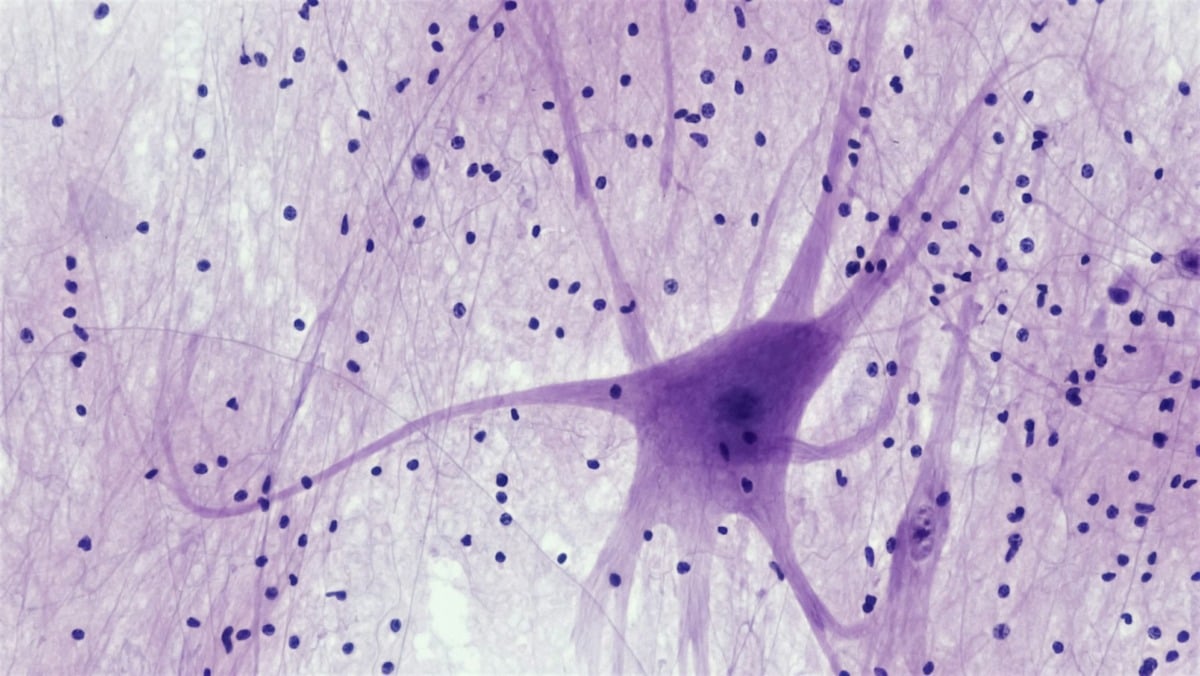

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a rare but severe neuropathic pain condition that causes intense, long-lasting pain, often following an injury or surgery. Patients frequently report some of the highest pain scores recorded in clinical practice, yet there is still no approved therapy. AKIGAI, a Norway-based company, is hoping to change the narrative in neuropathic pain with EGFR inhibitors.

CRPS is part of the broader spectrum of neuropathic pain disorders, which affect an estimated 7% to 8% of the population in Europe. Current treatments, typically opioids, anti-epileptics, or antidepressants, bring meaningful relief to only a fraction of patients and often come with side effects that limit long-term use. Despite the scale of the problem, there has been little innovation in the field for nearly two decades, leaving both doctors and patients with limited options.

AKIGAI is developing a therapy that repurposes EGFR inhibitors, long used in oncology, for neuropathic pain. The biotech plans to move into phase 3 trials in 2026, positioning itself in a therapeutic area where need is high and progress has been scarce.

Why the neuropathic and CRPS pain field has struggled

Over decades, the search for new therapies in neuropathic and CRPS pain has become a story of frustration. The science is messy, the patients are variable, and time and again, promising preclinical leads fail to translate into clinical benefit.

One central issue is translation itself. Much of what we know comes from rodent models. But human pain is subjective. The gap between animal behavior and human experience is huge. “We come from oncology, and we are self-made pain researchers. I found it astonishing to see how difficult it is, or almost impossible, for pain researchers to study human tissue. You rely all the time on rodent tissue, and we know that rodent models do not reflect what’s happening in humans very well,” said Christian Kersten, co-founder of AKIGAI.

Many candidate drugs show strong analgesic effects in rodents but then fall short in human trials, a pattern repeatedly documented in reviews of translational failure in pain research. “In oncology, we are used to taking a biopsy of a cancer and comparing it to healthy tissues. In the pain field, however, translational research is very hard to perform,” said Kersten.

Compounding that, trial after trial of ion channel–targeted drugs, sodium, calcium, and potassium channels, have ended in disappointment. Na_V1.7 inhibitors, once hyped as the dream target, have repeatedly failed in advanced trials due to lack of efficacy or design challenges. The logic is appealing: block hyperactive channels, quiet the pain signals. But in practice, patient heterogeneity, compensation by other pathways, and trial design limitations have undermined many programs.

Clinical trials themselves add another layer of complexity. In a meta-analysis of close to 130 randomized neuropathic pain trials, the estimated effect sizes of drugs have declined over time. The number needed to treat (NNT) for substantial pain relief has shifted from more favorable values in early trials to much less promising ones in recent studies. Placebo responses, variable baseline pain, inconsistent endpoints, and dropout all erode statistical reliability. Critics often point out that many trials lack mechanistic biomarkers or robust dose-finding data, relying instead on empirical dosing.

Side effects are also an issue in many drugs currently used to treat different entities of neuropathic pain.

“There are a lot of drugs out there that are mostly used off-label. Some have been shown to do some good, but in many cases, you have to treat eight to 10 patients in order for one of them to benefit from a 50% pain reduction. So, they are not effective enough to counterbalance their side effects. You could reach significant pain reduction with a higher dosage, but the patient would be asleep. We are talking about chronic pain conditions, which means a lifetime of taking drugs. So, when you have the patient in front of you, do you even want to treat them, give them a drug they can overdose on or get addicted to?” said Marte Cameron, AKIGAI’s co-founder.

Christian Kersten, AKIGAI’s co-founder, noted, however, that despite these challenges, a candidate managed to reach approval recently for acute pain (not neuropathic pain), Vertex’s sodium 1.8 inhibitor, suzetrigine. “There have been recent advances, especially one company, managed to get approval for a single ion channel inhibitor recently, although the effects have not been shown in neuropathic pain, and post-operative pain are quite modest. I think this might generate a stronger belief that it is possible to develop new pain drugs.”

Indeed, many large pharma companies gradually stepped back from pain research after the early 2000s. The risk/reward shifted: with repeated failures and regulatory uncertainty, pain became an unattractive domain compared to oncology or immunology.

“Before this recent approval, the last drug approval in neuropathic pain was in 2004, and the entire industry kind of shied away from it then. I think Vertex’s approval brings renewed belief,” said Kersten.

AKIGAI’s EGFR inhibitor, AKI-007: A story of serendipity

When Christian Kersten and Cameron first observed the pain-relieving effects of an EGFR inhibitor in a cancer patient more than 15 years ago, they didn’t set out to reinvent pain medicine. Kersten was then an oncologist running clinical trials in tumor immunology, and Cameron, a cancer physician with an interest in symptom management. Their patient, whose tumor had invaded the sciatic nerve, received an EGFR inhibitor and, within hours, rose from his wheelchair after months of near-total immobility.

“The next patient was a CRPS patient,” Cameron recalled. “She was pain-free the day after treatment and has been pain-free for thirteen years now.”

What started as a single-patient observation became the basis for a decade-long exploration that the two physicians now describe as serendipity followed by persistence. “We didn’t start from a hypothesis,” Cameron said. “We just made these incredible observations.”

Since then, they have treated more than a hundred patients with refractory neuropathic pain using six different EGFR inhibitors across eleven pain entities, reporting what they say are dramatic effects in roughly seventy percent of cases. “The patients frequently go from a pain score of nine to one or zero,” Kersten said.

The hypothesis, refined through subsequent animal and clinical data, is that EGFR signaling becomes abnormally active on damaged peripheral pain fibers. Downstream of that receptor, several ion channels involved in pain transmission are dysregulated. “At least four different ion channels are affected by the activated EGFR signaling,” Kersten explained. “That may be the main reason we see such dramatic responses.”

“Ion channels have been in the focus of neuropathic pain research for more than 20 years, and there have been countless failed clinical trials. And I believe that quite frequently, when you inhibit these ion channels, the drug candidates often only inhibit one ion channel at a time. So, the therapeutic window is quite small, and with EGFR inhibitors, at least four channels are impacted,” explained Kersten.

AKIGAI’s candidate, AKI-007, is an EGFR inhibitor optimized for peripheral selectivity and lower dosing than oncology formulations. Its detailed pharmacology remains confidential, but the company says the new regimen reduces systemic side effects to below 5%.

Cameron continues to practice palliative medicine in addition to her role at AKIGAI. “I think I’m the only doctor who can use EGFR inhibitors to treat neuropathic pain,” she said. “Some of these patients have been on them continuously for more than thirteen years, so it’s important that I keep this position so they can keep being treated consistently.”

AKIGAI is now preparing for a phase 3 trial in CRPS, planned for 2026, with the goal of bringing the first approved therapy for the condition to market. The company holds orphan designations in both the U.S. and Europe. “CRPS is an orphan condition that has never had a single drug approved. It is an open landscape for us, and we don’t have to beat anything but the placebo.”

For a field long defined by uncertainty and caution, their confidence is striking. Whether those early successes can translate into large-scale, placebo-controlled success will be the question that defines AKIGAI’s next few years.

Opportunities and challenges for AKIGAI and the broader field

One of the main challenges for the upcoming phase 3 trial has to be the clinical trial design. “We have to demonstrate efficacy first and foremost, right? So, we have to show that the positive effects are durable and that the drug is safe even at higher dosages than what we will administer. Luckily, because it’s a repurposed drug, we already know it is safe. To show that it’s effective, though, it is based on the patient’s reported outcomes, the subjectivity makes it riskier, but at the same time, we are confident that our design is good enough to demonstrate efficacy,” said Cameron.

As the company is confident in its trial and the efficacy of the candidate, Kersten noted that the challenges the company faces are a combination of things. “We are a startup operating in neuropathic pain with a repurposed drug, so we are catching all three red flags, which makes funding a challenge.”

However, Kersten also noted the company is well prepared. “We believe that we have better market protection than many new chemical entities. We have a safer dosing, too. We have strong regulatory protection that will prevent generics from arriving too soon, and I believe we will be the first line treatment for all neuropathic pain in the years to come.”

In the near term, the next few years will be revealing. Whether AKIGAI can convert its anecdotal promise into reproducible, regulatory-grade evidence will shape not just its own fate, but potentially the trajectory of pain drug development more broadly.

“It’s hard to believe that you can make a better drug without touching the EGFR receptor, and we have the use pattern on it. So, we feel comfortable that we can position ourselves quite well in the market. At the same time, we really look forward to more researchers and more companies going into this EGFR receptor field and looking into it and seeing its potential for the patients,” said Kersten.