Main findings

Our investigation showed that South Korea’s self-isolation policy, which required people infected with COVID-19 to stay home from work, had significantly different impacts on workers’ earnings depending on their employment contracts. Specifically, non-standard workers were approximately three times more likely than standard workers to experience income loss during mandatory self-isolation periods. This disparity stemmed from the unequal structure of sick leave arrangements in South Korea through two distinct mechanisms. First, a higher proportion of non-standard workers underwent unpaid leave compared to standard workers. Second, even when non-standard workers had access to paid leave, they were more likely to receive compensation below their regular wages. Our mediation analysis demonstrated that these two pathways contributed almost equally to the observed income disparities.

Our analysis further revealed substantial heterogeneity in income loss risk among different categories of non-standard employment. Compared to standard workers, atypical workers were 4.06 times more likely to experience income reduction, while part-time workers and temporary workers had 3.02 and 2.25 times the odds of income loss, respectively. Despite these varying risk levels, the relative contributions of the unpaid and partially paid leave pathways remained approximately equal across all three non-standard employment categories.

The robustness of these findings was confirmed through multiple sensitivity analyses. Our conclusions remained consistent after adjusting for various demographic and work-related potential confounding variables, employing more detailed classifications of region, industry, and occupation, and altering the reference group in our counterfactual mediation analysis.

Comparison with other studies

This study contributes to several fields of research. Our findings align with prior studies indicating that non-standard workers were hit harder than standard employees during the COVID-19 crisis [16,17,18,19,20], as was the case during previous economic downturns [44,45,46,47]. While these studies primarily examined the effects of reduced labor demand due to economic recessions, our focus was on assessing inequalities in the income impact of testing and isolation strategies aimed at mitigating the spread of COVID-19. In doing so, we sought to deepen our understanding of this pandemic and improve preparedness for future pandemics.

Our results complement, rather than contradict, previous research highlighting demographic disparities in the economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis [23, 34,35,36,37]. Notably, after controlling for employment type and occupation, we found that most demographic characteristics (sex, age, family composition, and residence region) did not significantly affect the probability of income loss during self-isolation, with education level being the only exception. This suggests that observed income loss disparities across population groups in South Korea during the pandemic were largely mediated through differences in job characteristics rather than through demographic factors directly. This finding underscores the importance of employment arrangements in determining economic vulnerability during public health emergencies.

Several studies have highlighted income insecurity as a primary determinant of low compliance with testing and self-isolation guidelines. Survey data from the United Kingdom during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that only 18% of symptomatic individuals requested a test, with only 43% isolated [10]. Higher rates of non-adherence were observed among individuals with lower socioeconomic status and facing greater financial hardship. A study examining the 2003 SARS outbreak in Toronto, Canada, which lacked comprehensive national paid sick leave requirements at that time, indicated that fear of income loss was the predominant reason healthcare workers failed to adhere to quarantine protocols [48]. Similar to our results, this study identified casual, part-time, and self-employed workers as those most afraid of the risk. A study of the Israeli population, under a system with limited statutory sick pay coverage, examined compliance attitudes during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [11]. The research found that 94% of respondents expressed willingness to comply with self-isolation if provided financial compensation for lost wages, whereas the compliance rate dropped to 57% in the absence of financial support. Our work adds to existing evidence by showing that these fears are grounded in reality; income loss during self-isolation was prevalent during this pandemic, particularly among non-standard workers.

This study is also relevant to research on the accessibility and adequacy gaps in sick leave benefits between standard and non-standard workers [31, 32]. These disparities have been documented across countries with varying income levels worldwide. A comprehensive review of sick leave policies across 193 countries revealed that, despite most countries guaranteeing paid sick leave to standard employees, the explicit inclusion of part-time workers in these benefits was limited—only 46% of high-income countries, 31% of middle-income countries, and 23% of low-income countries offered such protections as of 2019 [29]. In the United Kingdom, a 2020 survey of 7,718 workers demonstrated that the proportion of employees without employer-provided sick pay beyond the statutory minimum was substantially higher among those with temporary contracts or variable working hours than among those with permanent contracts or fixed schedules [49].

Similar gaps exist in the gig economy. A 2017 survey conducted by the European Parliament found that approximately half of digital platform workers in European countries and the United States did not have access to sickness benefits [50]. A recent study by the Fairwork project, which examined COVID-19-related policies across 191 platforms in 43 countries, including 11 OECD members, found that only 45.0% of platforms provided some form of sick pay during the pandemic [51]. Most of these platforms offered flat-rate sickness benefits to their gig workers who met certain eligibility requirements, with payments significantly below their respective countries’ minimum wage levels.

Consistent with this global evidence, our study revealed that differences in paid sick leave access led to significant disparities in earnings losses during COVID-19 self-isolation between standard and non-standard workers in South Korea. Our analysis also highlighted sick leave compensation rates as another critical factor; about half of the income loss gap was attributable to differences in the proportions of fully and partially compensated leave among workers who received paid sick leave for self-isolation.

Finally, our work is related to studies exploring differences in working conditions among non-standard employment arrangements. Prior research revealed that even within non-standard employment, workers are at increased risk of experiencing adverse external shocks when they are employed part-time rather than full-time, or when they lack a direct employment contract with the companies that use their labor [52,53,54]. In particular, an International Labour Organization (ILO) report demonstrates that informality and precariousness of work tend to increase in the order of standard, temporary, part-time, and atypical employment [13]. We provided evidence consistent with these findings by comparing workers’ income loss experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Policy implications

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed critical gaps in social protection systems worldwide. Like many countries, South Korea implemented substantial fiscal expenditures during the pandemic to provide income support for workers required to self-isolate [26, 30, 55]. However, our results revealed that these emergency measures were insufficient to protect a significant proportion of workers from income losses, particularly those in non-standard employment. This limitation highlights the urgent need for structural reforms in two key dimensions: extending paid sick leave coverage to all non-standard workers and enhancing wage replacement rates. Implementing these reforms would serve as an investment in both social equity and public health infrastructure, simultaneously protecting vulnerable populations, improving pandemic response capabilities, and fostering a more resilient society.

The results of our subgroup analysis also have significant implications for future pandemic preparedness. The disproportionate vulnerability of atypical and part-time workers documented in this study presents a substantial policy challenge as these forms of employment are expected to account for a growing share of jobs driven by sociodemographic, technological, and environmental changes over the coming decades [56, 57]. Current social protection frameworks designed around traditional employer-employee relationships may create systematic disadvantages for these workers; part-time workers often face exclusion due to minimum hours or earnings requirements, while atypical workers, particularly those in dependent self-employment, are frequently misclassified as independent contractors outside the scope of labor protections [13, 58]. Addressing these barriers requires both tailored measures for the least protected worker groups and broader reforms toward universal social protection [58]. Without such institutional changes, future public health emergencies will likely reproduce or exacerbate the socioeconomic inequities revealed by COVID-19, undermining both individual welfare and pandemic containment objectives. Social protection systems must evolve alongside changing labor markets to ensure robustness and resilience against future crises.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. The main strength is the use of a unique dataset that investigated workers’ experiences of income changes during COVID-19 self-isolation, which is rare in other datasets. It also covered a wide range of socio-demographic and occupational characteristics, which allowed us to compare workers with different employment contracts while adjusting for potential confounders. Furthermore, by considering workers’ receipt of paid sick leave during self-isolation, we could examine the institutional mechanisms through which non-standard employment was associated with a higher risk of income loss. Finally, our subgroup analysis revealed significant disparities between different types of non-standard work.

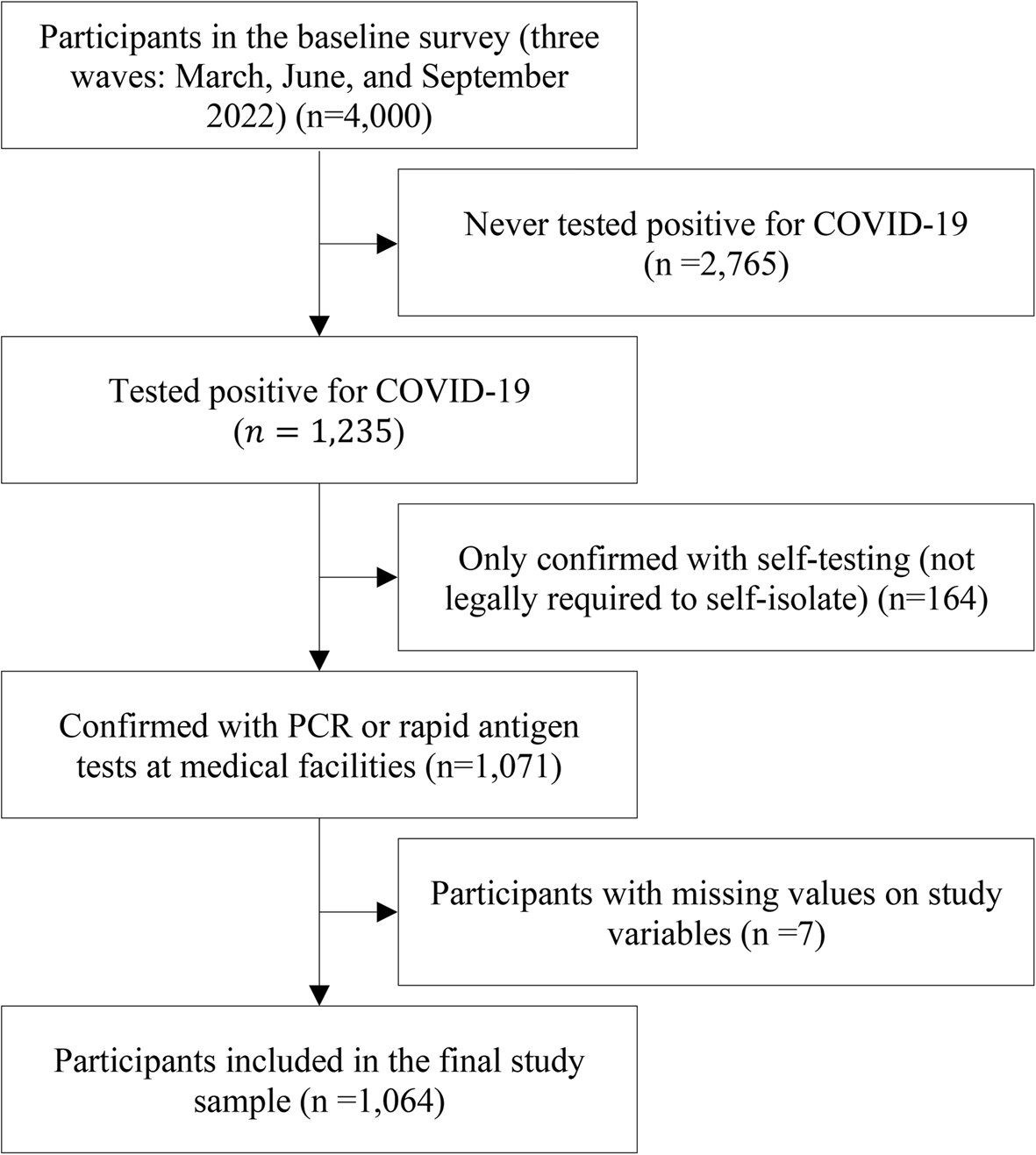

Our study has several limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, we employed cross-sectional data with a moderate sample size, which constrains our ability to draw causal conclusions. Despite adjusting for multiple observable confounders, omitted unobserved factors that simultaneously influence employment type and income loss during self-isolation may still bias our estimates. Establishing definitive causal relationships would require experimental or quasi-experimental methods, which were not feasible given the cross-sectional nature of our dataset. Our results should therefore be interpreted as associational evidence rather than conclusive causal effects.

Second, our reliance on self-reported data may introduce potential recall bias. However, we believe respondents could accurately recall their employment status, sick leave arrangements, and the occurrence of income loss during COVID-19 self-isolation since these were relatively recent and personally significant experiences at the time of survey participation. Selection bias could also influence our findings if individuals who experienced income loss were more motivated to participate in our survey, potentially overestimating the true prevalence of income loss during self-isolation. Even in this case, we have no reason to believe this would systematically differ between standard and non-standard workers, thus likely preserving the validity of our comparative analyses.

Third, as we used a dichotomous dependent variable indicating the occurrence of income loss, we could not compare the precise magnitudes of income changes across different employment types. This limitation, however, does not introduce bias into our findings but only constrains the scope of our analysis to the risk of income loss, excluding its depth or severity. It is worth noting that several previous studies [16, 20, 35] have similarly employed a binary dependent variable to compare the impacts of the COVID-19 recession on the risk of income loss across different population segments.

Fourth, we did not have information on the amount of money the respondents received from employer-provided sick pay or government-provided livelihood assistance. Mediation analysis using this information may yield results different from those obtained in this study. Given that the wage replacement rate of government livelihood support was generally much lower than that of employer-provided sick pay, disparities in earnings losses among employment types may be more attributable to gaps in the coverage of paid sick leave than our current estimates suggest.

Lastly, some of our findings may reflect country-specific features since South Korea is one of the few countries where employers are not legally obligated to offer paid sick leave to employees [30]. Future research should extend this analysis to other countries and investigate how institutional differences across countries shaped inequalities in COVID-19-related income losses by employment type.