Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

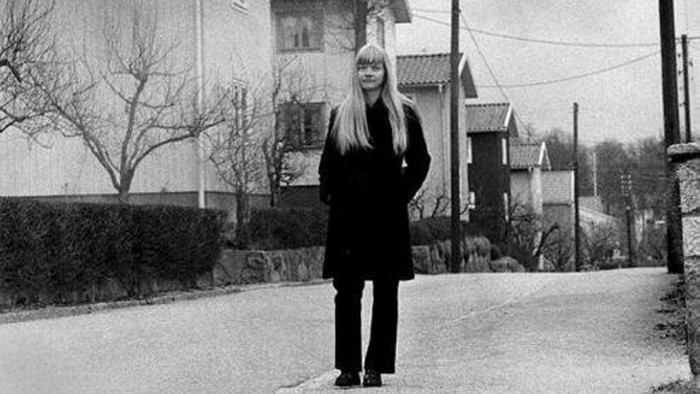

Stockholm, spring, late 1960s, and the city is glistening with potential: freshly laid concrete and laminated protest placards and the glass blocks of Sergels Torg and Kulturhuset rising against the sky. This is the backdrop for Gun-Britt Sundström’s 1976 novel Engagement, an instant classic upon its publication in the author’s native Sweden that has now been published for the first time in English.

Our protagonist, Martina, is a woman of this new age, energised by philosophy lectures and political discussions at cafés and screenings of Viridiana. She doesn’t want marriage or children or a traditional life, but her boyfriend, fellow scholar Gustav, is certain that he does.

The epigraph of the novel is taken from Kierkegaard, who is often referenced within: “Marry and you will regret it; do not marry and you will regret that too”. It’s hardly a surprising choice for a book whose original title, Maken, translates to “The Husband”, and whose plot is largely an examination of its central couple’s deliberation over whether or not to marry. For Martina, the happiness of coupledom is a form of somnambulance, the flicker of an eyelid that turns seconds into years, decades: “You get an apartment. You get a fiancé. You get a job. And then you’re stuck,” she thinks.

This anxiety lies at the heart of Engagement, a micro examination of a macro concern. The young people in the book are markedly different from the generation preceding them; du-reformen (a process of linguistic informalisation that saw, for example, the use of the starchy hierarchical pronoun “ni” abandoned in favour of the egalitarian “du”) is widely accepted, the oral contraceptive pill is freely available, and student-led political action — feminist, Marxist, anti-colonialist — is common. But the old structures still scaffold society. While Martina is able to get the pill, she has to pre-empt the doctor’s probing questions and pretend she has a fiancé, lest she be treated like her friend Harriet and be “considered too young although she was nineteen already”.

It may be tempting to see the book as a relic, a document of a half-century past. There has been somewhat of a gold-rush around “neglected” European novels recently, with the popularity of translated fiction resulting into a number of 20th-century authors being translated into English for the first time. But Engagement still feels effortlessly contemporary, even refreshing. This is both testament to Sundström’s light-touch, confessional style — captured in Kathy Saranpa’s translation — and a sad indictment that progress, particularly for women, has not truly materialised — and may even have backslid.

Although the refrain of “the personal is political” now has a plasticky, cliched ring to it, Sundström’s novel is a much-needed reminder of just how radical the concept was, and perhaps even how it can continue to be. The way Martina relates her feminist precepts to her own life still resonates (and perhaps always will), a determination not so much to “have it all” but to redefine what “all” means. As much as she loves Gustav, she is unwilling to reconcile herself to the identity of wife or mother, to resign herself to jam-making and full skirts and baby vomit. In this light, then, “all” is freedom: to have “a little while” to oneself, as Martina sees it.

Yet aside from writerly skill and timely resonance, part of why Engagement feels so immediate is that its strident politics are married to an eternal, universal central conceit: people not being able to love another as they want to be loved. “An idiot can see that Gustav is the right one,” Martina despairs. “But I’m the one who’s wrong!” For her, love is potential — for oneself, for society — a constant desire for more.

But what if that, too, can never be enough? The traditional narrative of domesticity, after all, provides a neat structure; beginning, subheadings, end. Its alternative is free verse.

Part of the book’s power comes from Sundström’s refusal to shy away from pangs of regret or loneliness — she is aware that there is always a pay-off, always a bargain struck: “I certainly don’t envy my colleagues their marriages,” Martina says at one point. “But I do envy them their summer cottages.”

Perhaps, then, another quote from Kierkegaard would have suited the epigraph: “Were I to wish for anything I would not wish for wealth and power, but for the passion of the possible, that eye which everywhere, ever young, ever burning, sees possibility. Pleasure disappoints, not possibility.”

Engagement by Gun-Britt Sundström, translated by Kathy Saranpa Penguin Modern Classics £18.99, 512 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X