They’re the boogeymen of science fiction, a paradox of science and quite possibly a key to understanding the universe.

Scientists have been scrambling to understand the mysterious forces of black holes for decades, but so far it seems they’ve found more existential questions than answers.

We know a black hole is so heavy that its gravity creates a kind of divot in the geometry of the universe, said Priyamvada Natarajan, a theoretical astrophysicist at Yale University.

“A black hole is so concentrated that it causes a little deep puncture in space/time. At the end of the puncture you have a thing called a singularity where all known laws of nature break down. Nothing that we know of exists at that point.”

Nova explosion ‘star’ over Ohio? Why NASA is excited about T Coronae Borealis

Understanding what science knows about black holes involves mysterious little red dots, the formation of galaxies, and spaghettification (the unpleasant thought experiment about what would happen to a person unlucky enough to be sucked into a black hole).

First, the good news: Black holes aren’t out to get us. They aren’t whizzing around the universe looking for galaxies, suns and planets to devour.

“They don’t just sneak up to you in a dark alley,” said Lloyd Knox, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Davis.

But our understanding of the very fundamentals of the universe has been transformed over the past decade by new telescopes and sensors that are letting scientists see more black holes and at every stage of their lives.

What to know about observatory: James Webb Space Telescope marks 3rd anniversary

This illustration shows a glowing stream of material from a star as it is being devoured by a supermassive black hole. When a star passes within a certain distance of a black hole – close enough to be gravitationally disrupted – the stellar material gets stretched and compressed as it falls into the black hole.

“Our understanding of the role black holes play, that they are an essential part of the formation of galaxies, is new,” said Natarajan.

Here what cosmic secrets are being revealed:

A new kind of black hole and a newly proven theory

The original understanding of how black holes formed was that when a sufficiently large sun (about 10 times or more massive than our Sun) reached the end of its life, it could explode into a supernova that then collapses back into a black hole. The matter can collapse down into something only a few miles across, becoming so dense that its gravity is strong enough that nothing, not even light, can escape. This is what is called a stellar mass black hole.

But in the past two decades, new types of black holes have been seen and astronomers are beginning to understand how they form. Called supermassive black holes, they have been found at the center of pretty much every galaxy and are a hundred thousand to billion times the mass of our Sun.

But how did they form?

“The original idea was that small black holes formed and then they grew,” said Natarajan. “But then there’s a timing crunch to explain the monsters seen in the early universe. Even if they’re gobbling down stellar gas, did they have the time to get so big? That was an open question even 20 years ago.”

In 2017, she theorized that these supermassive black holes from the early beginnings of the universe happened when galactic gas clouds collapsed directly in on themselves, skipping the star stage entirely and going straight from gas to a massive black hole seed, with a head start, that could then grow.

“Then guess what? In 2023 the James Webb telescope found these objects,” she said. “This is what a scientist lives for, to make a prediction and see it proven.”

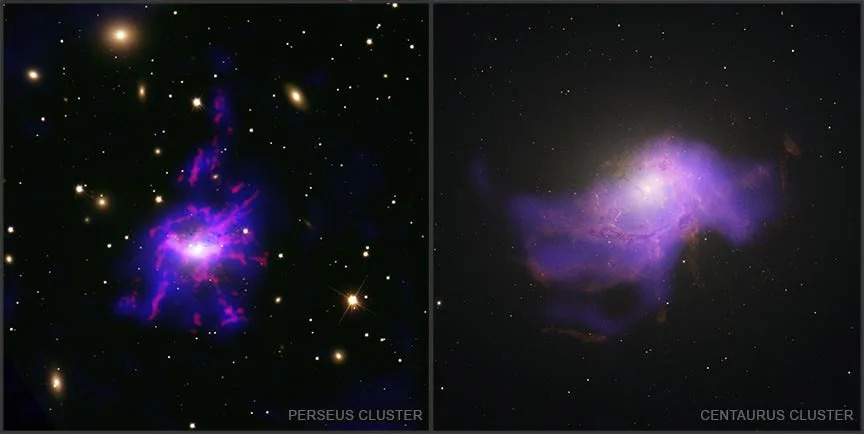

This composite images shown side-by-side of two different galaxy clusters, each with a central black hole surrounded by patches and filaments of gas. The galaxy clusters, known as Perseus and Centaurus, are two of seven galaxy clusters observed as part of an international study led by the University of Santiago de Chile

Black holes don’t suck everything into them

Because they have such massive gravity, black holes gobble up stellar gases and anything else that gets too close to them. But it’s not an endless process that ends up with the entire universe being sucked into them.

People sometimes worry that black holes are these huge vacuum cleaners that draw in everything in sight. “It’s not like a whirlpool dragging everything into it,” said Knox.

Black holes are really like any other concentration of mass, whether it’s a sun or a planet. They have their own gravitational pull but it isn’t infinite.

“If you’re far enough away, you’d just feel the gravitational force, just the way you’d feel it from a planet,” said Brenna Mockler, a post-doctoral fellow at the Carnegie Observatories at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Pasadena, California.

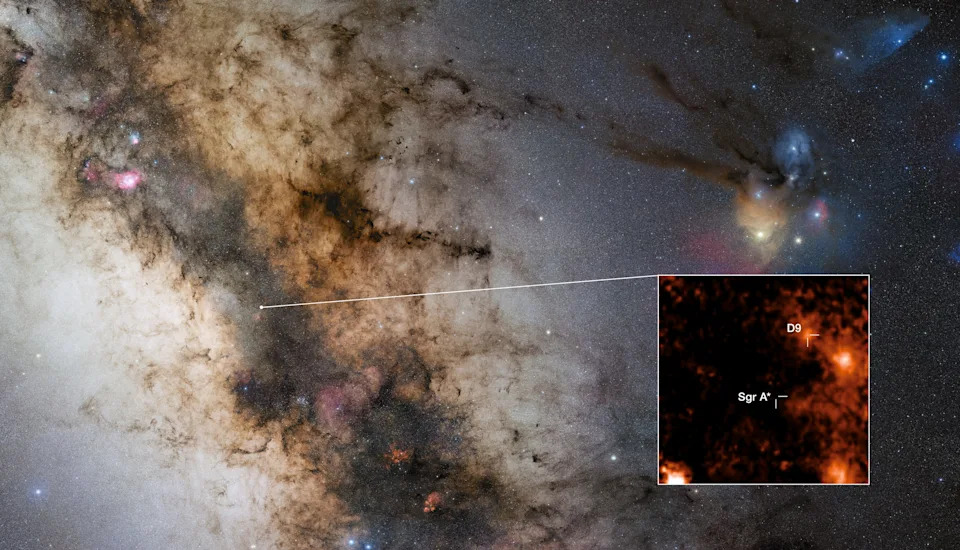

This image indicates the location of the newly discovered binary star D9, which is orbiting Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy. It is the first star pair ever found near a supermassive black hole.

If you fell into a black hole, you’d be ‘spaghettified’

All matter causes a dip or pothole in space/time, said Natarajan. A black hole is so heavy that its gravity creates a kind of divot in the geometry of the universe.

“The bigger the mass, the bigger the pothole,” she said.

Where that puncture leads is unknown.

“It’s an open question,” said Natarajan. “We don’t think it could be another universe, because we don’t know where in our universe it could go. But we don’t know.”

So what if a human being fell into a black hole? Astrophysicists have a word for it – spaghettification.

“If you were to fall head first into a black hole, the difference in gravity between your head and your toes would be so intense that you’d be stretched out and spaghettified,” Natarajan said.

Our Sun will never become a black hole

There’s no fear that our own Sun will become a black hole, said Knox. It’s not big enough.

“Lower mass stars burn through their hydrogen to make helium and then they’ll start burning helium into carbon. And then at some point it ends up just pushing itself all apart,” he said.

“Our Sun will eventually expand and envelop the Earth and destroy it – but that’s in 5 billion years, so you have some time to get ready. But it won’t become a black hole.”

A still unanswered mystery – ‘little red dots’

NASA’s super powerful James Webb Space Telescope began its scientific mission in 2022 and almost immediately picked up something that so far no one can explain: small red objects that appear to be abundant in the cosmos.

Dubbed “little red dots,” these objects have perplexed astronomers. They could be very, very dense, highly star-forming galaxies.

“Or they could be highly accreting supermassive black holes from the very early universe,” said Mockler, who is an incoming professor at the University of California, Davis.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What is a black hole? Scientists scramble to untangle cosmic mystery