BBC

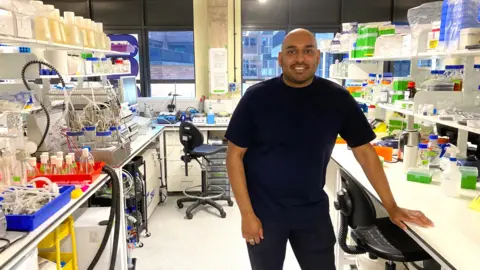

BBCIn an unassuming building in Stratford, east London, British start-up Better Dairy is making cheese that has never seen an udder, which it argues tastes like the real thing.

It is one of a handful of companies around the world hoping to bring lab-grown cheese to our dinner tables in the next few years.

But there has been a trend away from meat-free foods recently, according to the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB).

The statutory research organisation says that plant-based cheese sales across the UK declined 25.6% in the first quarter of 2025, while sales of cow’s cheese grew by 3%.

One reason for this, the AHDB tells the BBC, might be because the number of vegans in Britain is small – just 1% of the population (the Vegan Society puts it at 3%), far fewer than the amount of dairy cheese eaters – and has slightly declined lately.

The Vegan Society insists that the meat-free food market remains “competitive” and steady.

Those Vegan Cowboys

Those Vegan CowboysOther reasons may be concerns about health and price. A recent government survey found that that food being ultra-processed – a key challenge with vegan cheese – was the second-greatest concern for consumers, the first being cost. Plant-based cheese is generally more expensive than cow’s cheese, the AHDB says.

So are these efforts a recipe for success or disaster? Some think the coming years present an opportunity.

In the Netherlands, Those Vegan Cowboys expects to bring its cheeses to the US later this year, and Europe in three to four years due to regulatory hurdles. This is because lab-made cheeses count as a “novel food” and so need EU approval to go on sale.

Its chief executive, Hille van der Kaa, admits the appetite for vegan cheese is low right now, but her company is targeting a “silent revolution” by swapping cheeses people don’t often think about.

“If you buy frozen pizza, you don’t really think of what kind of cheese is on that,” she explains. “So it’s quite easy to swap.”

Meanwhile, French firm Standing Ovation plans on launching in the US next year, and in the UK and Europe in 2027.

And back in Stratford, London-based Better Dairy hasn’t launched its lab-grown cheese yet because it would cost too much right now.

But chief executive Jevan Nagarajah plans to launch in three or four years, when he hopes the price will be closer to those seen in a cheesemonger, before getting it down to the sorts seen in a supermarket.

So does it taste any good?

Better Dairy invited me – a committed carnivore and dairy devotee – to its lab to poke holes in this new cheese.

Currently, the company is only making cheddar because it sees vegan hard cheeses as having the biggest “quality gap” to dairy cheeses. It has made blue cheese, mozzarella and soft cheese, but argues the proteins in dairy don’t make as big a difference in taste.

The process starts with yeast that has been genetically modified to produce casein, the key protein in milk, instead of alcohol. Jevan says this is the same technique used to produce insulin without having to harvest it from pigs.

Other companies also use bacteria or fungi to produce casein.

Once the casein is made through this precision fermentation, it is mixed with plant-based fat and the other components of milk needed for cheese, and then the traditional cheese-making process ensues.

Having tried Better Dairy’s three-month, six-month and 12-month aged cheddars, I can say they tasted closer to the real thing than anything else I’ve tried. The younger cheese was perhaps a bit more rubbery than usual, and the older ones more obviously salty. On a burger, the cheese melted well.

Jevan accepts there’s room to improve. He says the cheese I tried was made in his lab, but in future wants artisanal cheesemakers to use the firm’s non-dairy “milk” in their own labs to improve the taste.

As the company cannot use dairy fats, it has had to “optimise” plant-derived fats to make them taste better.

“If you’ve experienced plant-based cheeses, a lot of them have off flavours, and typically it comes from trying to use nut-based or coconut fats – and they impart flavours that aren’t normally in there,” Better Dairy scientist Kate Royle says.

Meanwhile, Those Vegan Cowboys is still focusing on easy-to-replace cheeses, like those on pizzas and burgers, while Standing Ovation says its casein can make a range of cheeses including camembert.

Will these new cheeses find their match?

It’ll be a tall order. Of those who bought vegan cheese on the market in the past year, 40% did not buy it again, according to an AHDB survey – suggesting taste may be a turn-off.

Damian Watson from the Vegan Society points out that resemblance to the real thing may not even be a good thing.

“Some vegans want the taste and texture of their food to be like meat, fish or dairy, and others want something completely different,” he tells me.

And Judith Bryans, chief executive of industry body Dairy UK, thinks the status quo will remain strong.

“There’s no evidence to suggest that the addition of lab-grown products would take away from the existing market, and it remains to be seen where these products would fit in from a consumer perception and price point of view,” she tells the BBC.

Studio Lazareff/Antoine Repesse

Studio Lazareff/Antoine RepesseBut both Better Dairy and Those Vegan Cowboys tout partnerships with cheese producers to scale up production and keep costs down, while Standing Ovation has already struck a partnership with Bel (makers of BabyBel).

Standing Ovation’s CEO Yvan Chardonnens characterises the recent unpopularity as a first wave in the vegan “analogues” of cheese faltering because of quality, while he hopes that will improve in the next phase.

Besides the current concerns about a shrinking vegan market, taste, quality and price, the issue of ultra-processed foods is one that these companies may have to grapple with.

They argue a lack of lactose, no cholesterol and lower amounts of saturated fats in lab-made cheese can boost its health benefits – and that any cheese is processed.

Precision fermentation may also allow producers to strip out many ultra-processed elements of current vegan cheeses.

Hille suggests it’s a question of perception. People have a “romanticised view” of dairy farming, she says, despite it now being “totally industrialised” – a point backed by AHDB polling, which found 71% of consumers see dairy as natural.

“I wouldn’t say that’s really a traditional, natural type of food,” Hille argues.

“We do have an important task to show people how cheese is made nowadays.”