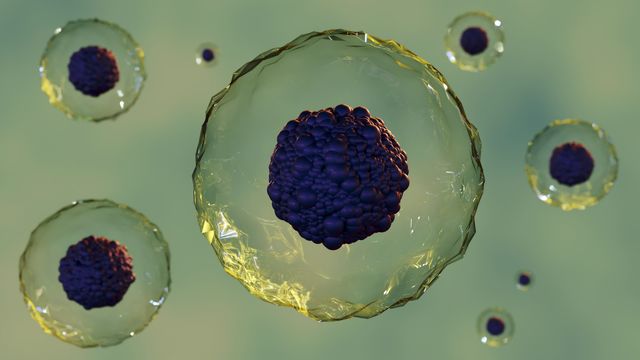

The secretory pathway in eukaryotic cells is crucial for maintaining cellular function and physiological activities, as it ensures the accurate transport of proteins to specific subcellular locations or for secretion outside the cell. A…

The secretory pathway in eukaryotic cells is crucial for maintaining cellular function and physiological activities, as it ensures the accurate transport of proteins to specific subcellular locations or for secretion outside the cell. A…