Very massive stars (VMSs)have had a massive impact on the formation of our universe. However, there aren’t very many of them, with only around 20 known specimens in the Milky Way and Large Magellanic Cloud. Even observing those is difficult for the current generation of telescopes, which is where an unexpected technological champion might play a role. According to a new paper by Fabrice Martins of CNRS and a group of European and American researchers, the upcoming Habitable World Observatory (HWO) might be our most useful tool when it comes to finding these elusive giants.

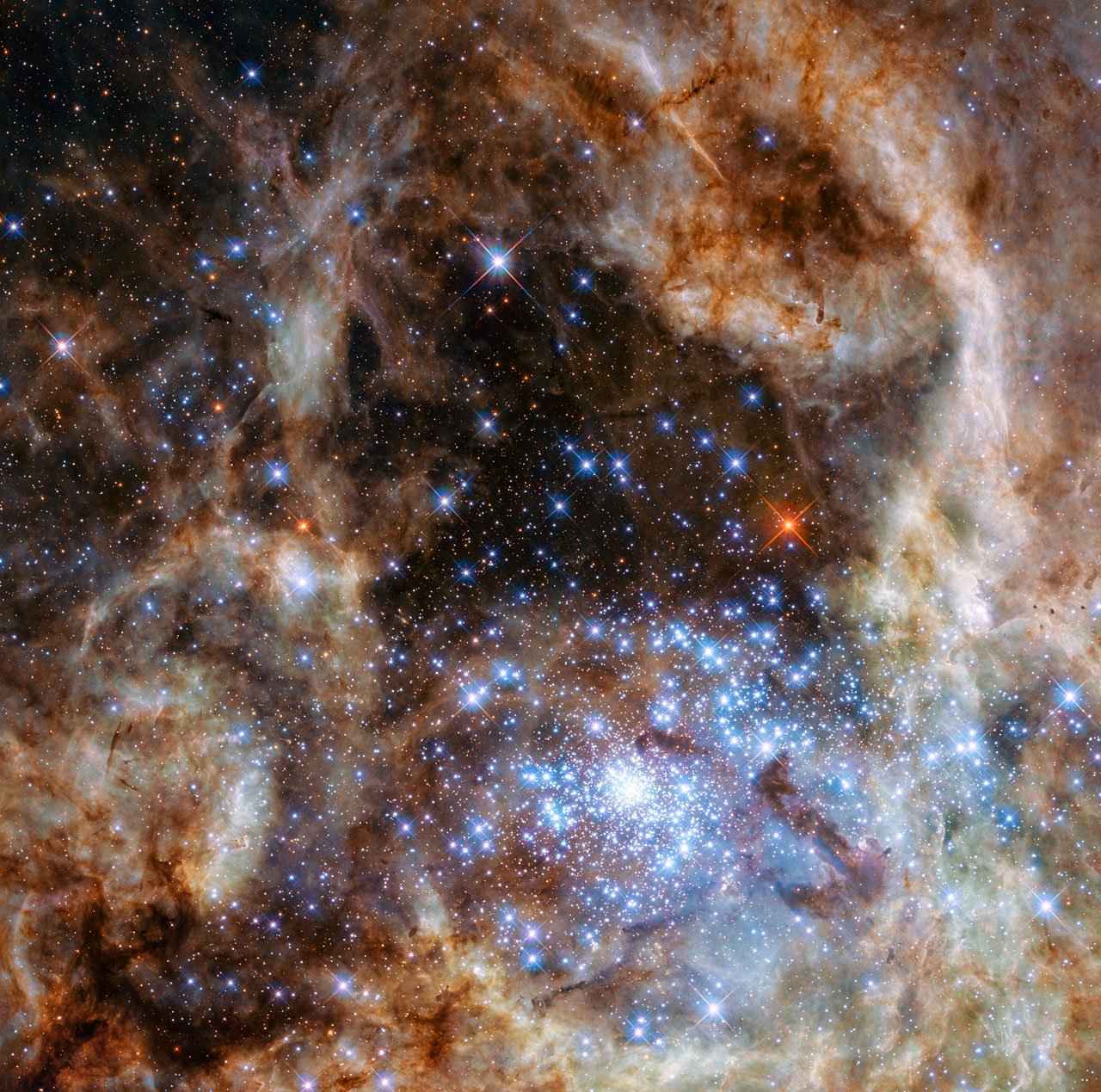

VMSs are typically huge, around hundreds of times the size of our Sun. As such, they are much brighter than a typical star, and have much higher mass loss rates, making them prime candidates to have seeded the local galactic area with “metals”, anything other than hydrogen and make up a large amount of the building blocks of all planets, asteroids and moons. However, they also are typically found in star clusters where they are surrounded by dozens or hundreds of other, normal stars.

To find these (admittedly very large) needles in the haystack of these clusters, a telescope would need extremely high spectral resolution, and that is exactly what the HWO provides. With an angular resolution of around 5 milli-arc-seconds (mas), it would be possible to resolve individual stars in most of the clusters where the VMSs reside, most of which would require between .5 to 110 mas.

However, it’s not enough to resolve individual stars – it’s important to confirm the star itself is “very massive”, as opposed to normal sized, or even just “massive”. The “very” in the name isn’t just hyperbole, it actually signifies a different physical process that these stars undergo, making that distinction important.

Fraser talks about the biggest star in the universe.

To differentiate between the types of very large stars, astronomers will look at the individual star’s optical and UV spectra. This is another area where the HWO has an advantage – ground-based telescopes might have the resolution to resolve these individual stars, but they lack the ability to see in UV due to it being blocked by our atmosphere.

There are several spectral features astronomers will distinguish, including spectral lines around HeII 4686 (that’s the helium-2 spectral line at 4686 Angstroms, not a name intended to scare astronomers away from studying it) and CIV 5801-12, which is emitted by a triply ionized carbon atom and is clearly defined at two different spectrum line – 5801 and 5012 Angstroms. Each of those lines help differentiate between a VMS and a Wolf-Rayet star, another type of massive star that is a descendant of the truly massive stars astronomers are looking for.

Ultimately what astronomers are looking for is a bound on the speed of mass loss in these stars compared to their metallicity. That map would help inform galactic evolution models, and show how things like planets and even other, smaller stars take shape. However, VMSs only exist for a few million years before they either collapse into a black hole or explode into a supernova. Given their relatively short lifetime, rarity, and importance to the evolution of both planets and stars, astronomers are hopeful they’ll be able to collect plenty more data about these critical stars, even if they have to wait until at least the early 2040s, which is the earliest HWO could potentially launch if it clears all the hurdles put into place before then.

Dr. Becky talks about the capabilities of the HWO.

Learn More:

F. Martins et al – Very Massive Stars with the Habitable Worlds Observatory

UT – Very Massive Stars Expel More Matter Than Previously Thought

UT – The Galactic Center Struggles to Form Massive Stars

UT – Giant Cluster is Spitting Out Massive Stars