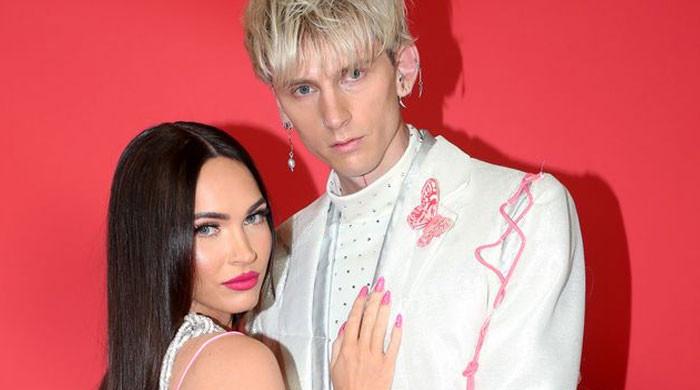

Megan Fox and Machine Gun Kelly are reportedly closer than before after welcoming their baby daughter

As per a recent report by People, things between the…

Megan Fox and Machine Gun Kelly are reportedly closer than before after welcoming their baby daughter

As per a recent report by People, things between the…