An extraordinary fossil has blown the socks of palaeontologists as it was found to contain the soft tissues of a Temnodontosaurus ichthyosaur, marking the first time we’ve ever found soft tissue remains of a giant ichthyosaur and introducing new-to-science features that reveal how they hunted. The discovery is going to revolutionize the way we look at ichthyosaurs, so said study co-author and palaeontologist Dr Dean Lomax, who knows a thing or two about these extinct marine reptiles.

You just know that this fossil is going to revolutionise the way we look at and reconstruct these creatures.

Dr Dean Lomax

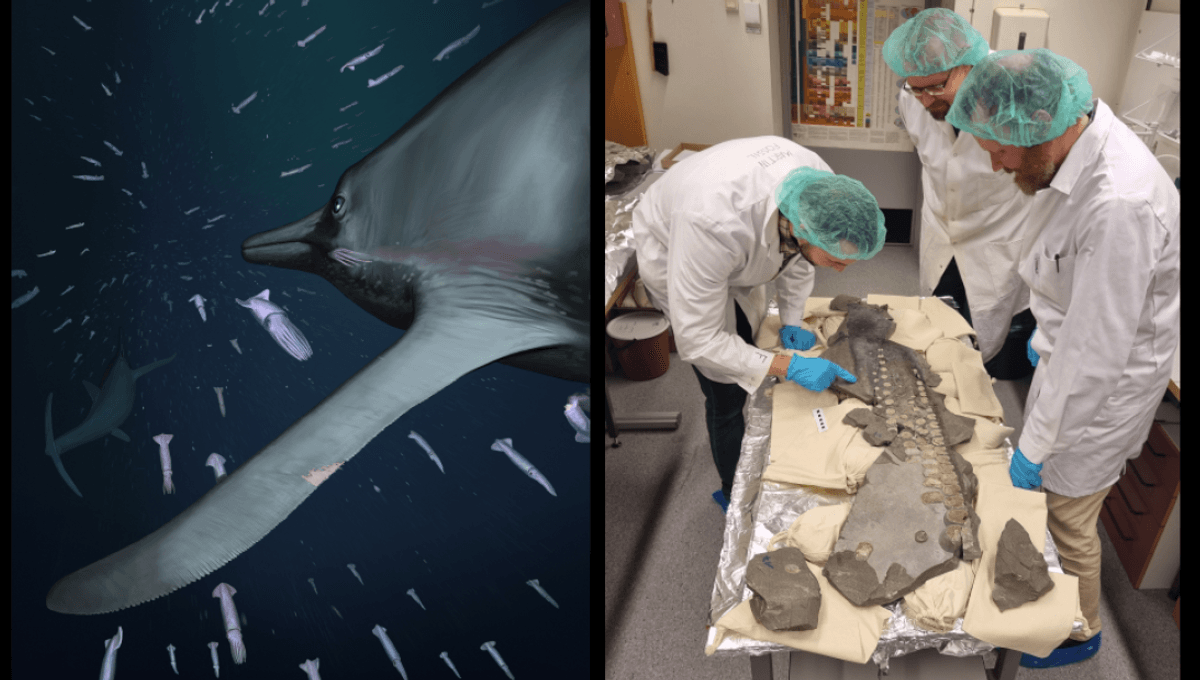

“Honestly, when I first saw this specimen in person, laid out on the kitchen table, no less, at Georg’s house (the collector), I was stunned into silence,” Lomax told IFLScience. “That says a lot about me (and this fossil), considering that I usually never shut up talking about fossils. But the extremely remarkable details, not only of the skin, but the striped pattern, the incredible winglike shape and those ‘spike-like’ structures – that we come to term chondroderms – reveal features that no other human had seen before.”

“The three of us stared at this fossil in awe. One of those goosebump-type moments where for that split second you just know that this fossil is going to revolutionise the way we look at and reconstruct these creatures. Remarkable for a group of ancient animals that we’ve known for over two centuries. It is the sort of discovery that 10-year-old ‘Dino Dean’ could have only ever dreamed of.”

The spectacular 183-million-year-old soft-tissue fossil of an ichthyosaur flipper.

Image credit: Courtesy of Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren

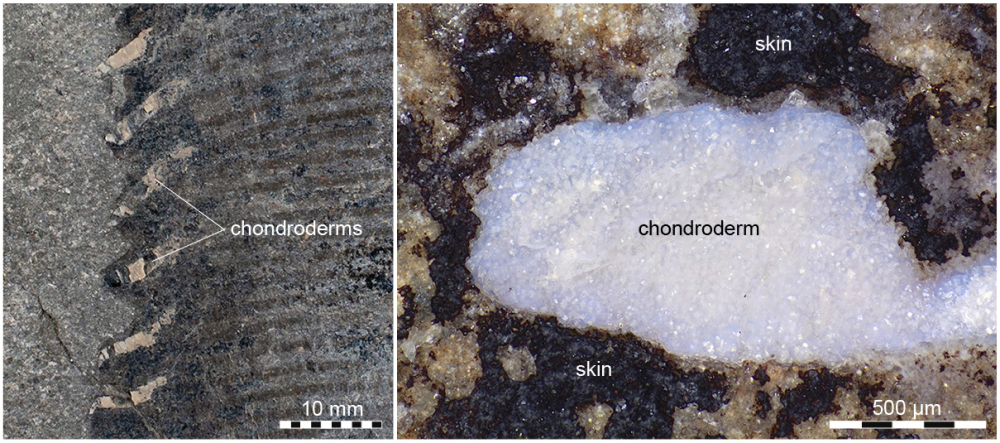

The fossil is that of a meter-long front flipper of the large Jurassic ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus that lived 183 million years ago. The flipper has a serrated trailing edge that’s reinforced by cartilaginous features scientists had never seen before, and have since named chondroderms. Lomax told IFLScience these chondroderms have “never been observed in any living or extinct animal,” and they reveal what kind of hunter this ichthyosaur was.

It’s thought this set-up provided hydroacoustic benefits, effectively enabling “silent swimming” that meant predatory ichthyosaurs could ambush their prey. We already know that ichthyosaurs had big old dinner plates for eyes, and it seems that coupled with these chondroderms, they must have been the ultimate stealth hunters in the dimly lit pelagic environment.

New-to-science features call for new-to-science names. Behold: an ichthyosaur chondroderm.

Image credit: Courtesy of Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren

This discovery is already shaping how we view ichthyosaurs going forward, and the fossil could be the key to uncovering many other details about these magnificent marine hunters.

The origins of ichthyosaurs have remained a bit of a mystery, but perhaps these unusual structures might help us to unravel similar features in more ancient creatures.

Dr Dean Lomax

“There are a couple of questions that we hope this fossil will answer, or at least begin to unpack,” said Lomax. “One, particularly, is whether these structures – and this unique behaviour – was restricted to this ichthyosaur, other ichthyosaurs or even other ancient marine reptiles. Or, in fact, whether similar structures evolved in other ancient creatures, but we’ve just not found them yet.”

“All of this, and indeed these structures, also open up further details about ichthyosaur origins. The origins of ichthyosaurs have remained a bit of a mystery, but perhaps these unusual structures might help us to unravel similar features in more ancient creatures, perhaps providing an archaic link. Time will tell.”

The study is published in the journal Nature.