One challenge of dieting is maintaining healthy eating habits, avoiding the so-called ‘yo-yo dieting’ effect. Now a new study suggests that effect might be closely linked to the bacteria living in our guts.

A team led by researchers from the University of Rennes and Paris-Saclay University in France ran a series of experiments on mice, measuring their reactions to rotating shifts in diet across several weeks.

The animals’ food regimes alternated between a standard diet and a high-fat, high-sugar diet intended to stand in for unhealthy Western diets. This yo-yo dieting simulation triggered signs of binge eating in the mice as soon as they returned to a less healthy diet.

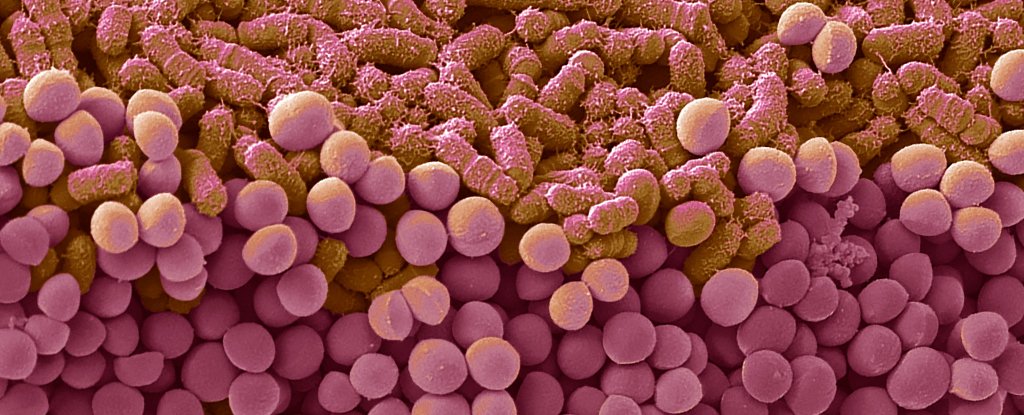

What’s more, there were long-lasting changes in the mice’s gut bacteria, changing their internal metabolism. Crucially, when the altered gut bacteria were implanted in mice that hadn’t been dieting, they showed the same binge eating behavior. It’s as if dieting creates shifts in the gut microbiome that then bring on unhealthy eating patterns.

Related: The Weight Loss Paradox: Shedding Significant Pounds Can Be Deadly For Some

“We showed that alternation between high-energy and standard diet durably remodels the gut microbiota toward a profile that is associated with an increase in hedonic appetite and weight gain,” write the researchers in their published paper.

By carefully analysing the brain patterns of the mice on the dieting schedule, the researchers could see that they were probably eating for pleasure rather than because they were hungry – as if the brain’s reward mechanism had been rewired.

While we can’t be sure this applies to humans, the results strongly suggest diet cycles could bring on certain shifts in the mix of bacteria in the gut that make it harder to maintain a healthy diet.

The unique make-up of bacteria in our guts has a substantial impact on our health, affecting our brain activity and risk of disease, for example. This microbiome can in turn be influenced by disease, diet, and our environment.

“Weight maintenance during restrictive yo-yo dieting might be impeded not only by metabolic adaptations but also by modified food reward-related processes,” write the researchers.

By improving our understanding of yo-yo dieting and the disordered eating patterns that can come with it, the hope is that we can improve therapies for tackling obesity and promoting healthy eating – perhaps by targeting particular types of gut bacteria.

One way to extend the research may be to closely examine the types of bacteria changes that are triggered by yo-yo dieting, and the biological mechanisms those microbiome shifts affect that make binge eating more likely. This also needs to be documented in human trials too, of course.

“More work is definitely needed to fully understand the mechanisms at play in this model, especially regarding the gut microbiota to brain transduction pathways involved in this weight cycling-induced altered eating behavior,” write the researchers.

The research has been published in Advanced Science.