This year is the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth and she hasn’t aged a bit as the cultural touchstone of classy romance. Her Pride and Prejudice anti-hero, Mr Darcy, perennially pops up in his breeches in Instagram memes, while Regency feminist, Elizabeth Bennet has been brought to life by a host of contemporary actors.

Along with new screen versions of Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (starring Daisy Edgar-Jones) and a Netflix version of P & P, there have been adaptations of her classics Persuasion, Emma, Northanger Abbey, and Mansfield Park. And, there are numerous biographies and biopics including a TV drama about Jane’s sister, Cassandra, who burnt most of Jane’s letters.

Review: The Novel Life of Jane Austen: A Graphic Biography –

Janine Barchas, Isabel Greenberg (Hachette)

Now, there is also a graphic biography: The Novel Life of Jane Austen, written by Janine Barchas and illustrated by Isabel Greenberg.

Together, they have co-created a storyboard for the domestic life that framed Austen’s writing, encompassing her closeness to both Cassandra and her brother Frank, who joined the navy and liked to sew.

Unlike a “cradle to grave” biography, Barchas begins with a teenage Jane in London with Frank touring an exhibition about Shakespeare and his work. We then follow her, in illustrative comic boxes and speech bubbles, through her publishing rejections, her breakthrough debut Sense and Sensibility, and her rise to become one of most beloved writers in the canon of English literature.

The book ends beyond the grave, flashing forward to the present, in a scene where contemporary fans – Janeites – visit Jane Austen’s House, the cottage in Hampshire where Austen lived when she revised and published her six novels.

It’s also a sign of subtle structural polish. Now Jane Austen is as deserving of her own gallery as Shakespeare was when we first met Jane as a young, unpublished author.

Thinking in pink

Barchas – an “Austenite”, as Austen scholars are called – is the author of The Lost Books of Jane Austen, a study of the mass market editions of Austen’s work. (The Novel Life touches on Austen’s posthumous appeal with a scene where readers buy Austen books for one shilling at a railway station after her death, aged 41.)

Barchas also wrote Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location and Celebrity, which links Austen’s characters to well known locations and figures in her era.

Isabel Greenberg

Barchas is the co-creator of the interactive digital exhibition, What Jane Saw, which invites us to visit two art exhibitions witnessed by Jane Austen: the Sir Joshua Reynolds retrospective in 1813 or the Shakespeare Gallery as it looked in 1796. The Novel Life, however, is a more definitive life story. It’s also best read in print (although it is available as an e-book) to appreciate Greenberg’s illustrations and graphic format.

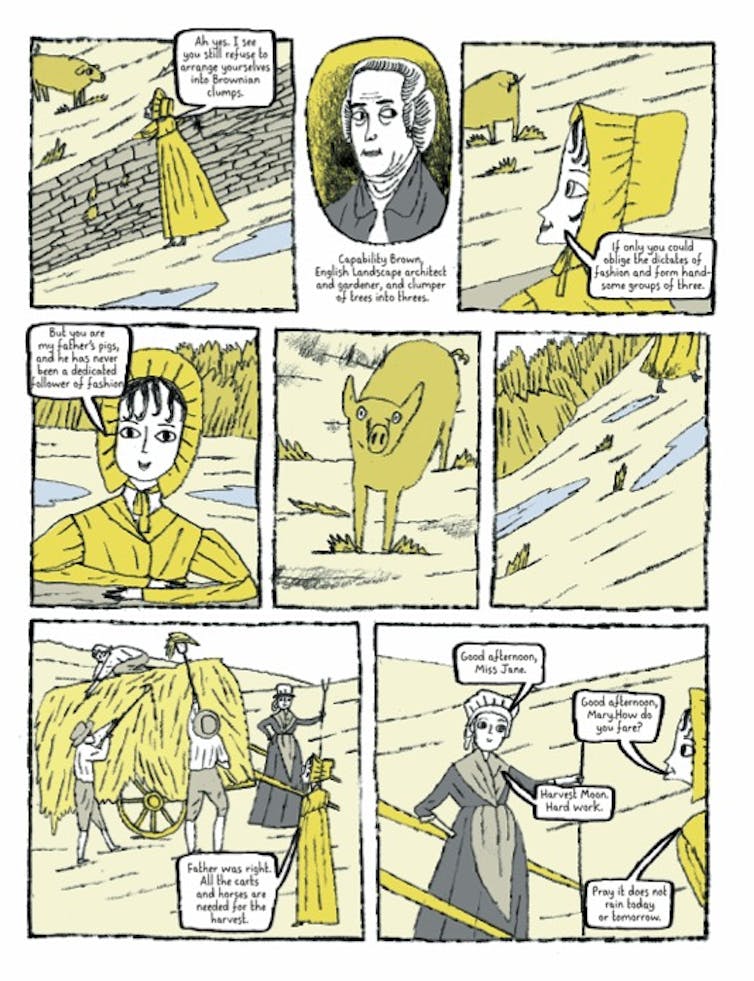

The Novel Life is a gentler, less dramatic style than traditional comics with six-pack superheroes or Japanese manga, similar to Greenberg’s previous literary graphic biography foray, Glass Town, about the Bronte sisters.

For the Novel Life, Greenberg has drawn a world in which Austen is whimsical, with expressive eyes looming under her signature bangs. She and her sister Cassandra appear in bright yellow or blue empire line dresses.

Most scenes are illustrated in a muted palette of yellow, blue and grey. This palette, Barchas reflects in the preface, represents “the relative quiet of her (Austen’s) life”.

When Jane is thinking or writing however, the pages transform into vivid shades of pink to symbolise her imagination and inspiration. In these pages, The Novel Life is at its best, showing graphic biography can be both captivating and deceptively sophisticated.

Archival nods

Is a graphic biography really a biography in the conventional understanding of the genre? It can upset the perceived rules. Anticipating this, in the preface, Barchas reminds us:

Any biography of Austen, and there are many, exists at the intersection of speculation and research.

This book is at this intersection. While the dialogue is largely invented, it is grounded in Barchas’ expertise and there is a glossary of sources at the end.

Throughout, there are also nods to the archive. Barchas begins with a scene of Jane in 1796 writing a letter to Cassandra at a desk while staying in London – one of the few not burnt.

A speech bubble quotes an extract from it:

Here I am once more in this scene of dissipation and vice, and I begin already to find my morals corrupted.

There are also Post-it style notes, separate to the bubbles, offering extra biographical context for readers less familiar with the intricacies of Austen’s story. A key scene happens when Jane, 22, receives her first rejection by a publisher for her manuscript “First Impressions” and is comforted by the loyal Cassandra. The note reads:

Jane would carry out more than a decade and a half of revisions before she dared to offer the manuscript to another publisher, who released it in 1813 as Pride and Prejudice.

Because of their visual casualness, importantly the notes don’t interfere with the intimate, engaging tone of the story.

Isabel Greenberg

‘Easter eggs’

For Austen’s committed “Janeite” fan base, Barchas promises “cheeky easter eggs” in the preface. Janeites can delight in well-quoted lines from the novels that appear as dialogue or a character’s thoughts.

Look, for instance, for Jane reading at a dinner party from P & P: “It’s a truth universally acknowledged […]” and “she is tolerable but not handsome enough to tempt me […]”.

It’s a truth universally acknowledged too that graphic biography can be confused with the graphic novel, now the third most popular literary genre in sales after general fiction and romance.

But, dear reader, there’s a tradition of life writing in the medium. The Pulitzer Prize winning graphic biography/memoir, The Complete Maus, told Art Spiegelman’s father’s story of the Holocaust to his son, (Art) who struggled to understand his father. Maus portrayed Jewish people anthropomorphically as mice and Nazis as cats. It was described by The New Yorker “as the first masterpiece of comic book history”.

Other high points in graphic biography include Peter Bagge’s Woman Rebel, the story of birth control campaigner Margaret Sanger, published in 2013.

Not everyone will appreciate a work diverging so dramatically from the expectations of a traditional biography. And those who will most appreciate or scrutinise The Novel Life are yes, the Janeites and Austenites.

Regardless, Austen comes to graphic life in the mind and hands of Barchas and Greenberg. More generally, for those of us who like our biographies in vivid colour – literally – and enjoy experiments in nonfiction storytelling, it’s a delightful reading experience, just like Jane Austen.