As the world grapples with land scarcity, climate threats, and the urgent need for clean energy, a new frontier is emerging: the floating economy. Defined by engineered, buoyant structures—floating solar farms, wind platforms, housing, aquaculture units, data centers, and logistics hubs—it is reshaping how we inhabit and utilize the planet’s waters. This multifaceted domain, a subset of the broader blue economy, transforms oceans, seas, lakes, and rivers into spaces for sustainable growth.

The floating economy matters for a number of reasons:

● Land Scarcity & Urban Pressure: Coastal cities face mounting constraints on land supply. Floating structures offer scalable solutions—expanding real estate, infrastructure, and amenities without resorting to land reclamation or new territory.

● Climate Adaptation: With accelerating sea-level rise and frequent flooding, floating infrastructure adapts naturally—rising as waters do—providing resilient housing, energy, and community platforms.

● Renewable Energy Transition: Floating offshore wind and photovoltaic systems unlock energy production in deeper waters and reservoirs, often with higher efficiency and fewer land-use conflicts.

These drivers converge to create a rapidly expanding market. Global floating solar could reach USD 75 billion by 2034 (CAGR ~27%) with ~49% share in Asia-Pacific. Floating wind, too, stands central to decarbonization plans.

Global Outlook: From Pilots to Mainstream

Floating infrastructure is evolving beyond novelty applications:

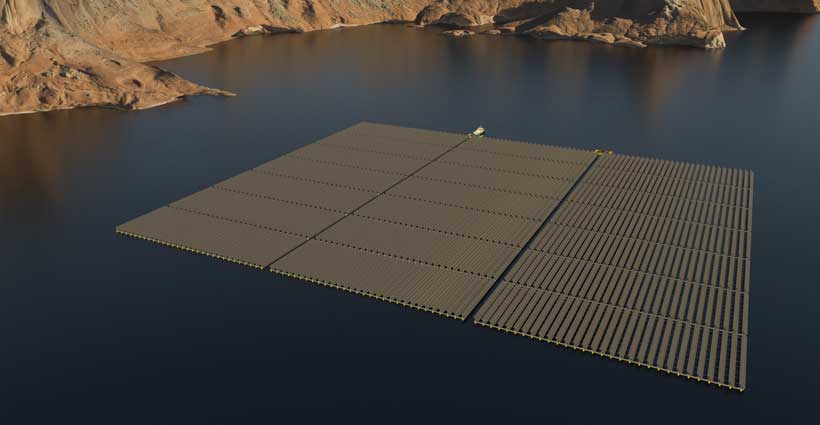

● Floating Solar Photovoltaics (PV): Once limited to meter-scale installations, projects now exceed hundreds of MW. China has built massive integrated floating solar farms in former coal-mining reservoirs, while countries like India and Indonesia are deploying them atop inland water bodies to reduce evaporation and avoid land-use conflicts.

● Floating Offshore Wind: Enabled by deeper-water turbine designs, floating wind opens vast new areas. Japan’s policy enabling wind farms in EEZs (10 GW by 2030, up to 45 GW by 2040) confirms global momentum. Norway’s Hywind Tampen and France’s Provence Grand Large are commercial-scale examples pioneering the sector.

● Multi-Use Platforms: Innovations like aquaculture-wind hybrids and floating data centers are overlapping functions to optimize capital, ecosystem services, and resilience. In Norway and China, floating platforms now support simultaneous fish farming, power generation, and marine biodiversity enhancement.

As capital costs fall and permitting processes become streamlined, what was once experimental is fast becoming scalable. Leading maritime cities such as Singapore, Busan, London, Shanghai, and Oslo are seizing the opportunity to gain from this rising tide.

In Singapore, the city-state is utilizing its reservoir and harbor infrastructure. Singapore leads with floating solar (e.g., 60 MW on Tengeh Reservoir) and pilots for hybrid energy-storage platforms. It is also charting future floating neighborhoods to alleviate land constraints and build adaptive communities. Plans are underway to pilot floating data centers and plug floating infrastructure into Singapore’s smart-city grid, integrating AI-based monitoring and predictive maintenance systems.

In the Dutch port city of Rotterdam, home to the world’s first floating dairy farm and hexagonal community parks, Rotterdam has embraced modular water-based development. Its port is being retrofitted to support floating-wind assembly and mobile logistics solutions, driving both ecological and economic value. The Netherlands has committed to embedding floating construction into long-term national housing and climate adaptation strategies, with firms such as Blue21 and DeltaSync leading innovation.

Meanwhile, the international finance center that is London is the epicenter for financing the UK’s scaling of its floating offshore wind toward its 2030 net-zero targets, issuing billions in upgrades to port infrastructure and supply chains. Floating hospitality and leisure venues are also gaining traction on the Thames and Manchester waterways. With Crown Estate funding and newly launched offshore wind leasing rounds, floating wind projects off the coasts of Wales and Scotland are forecast to power 4-5 million homes by 2035.

In the Norwegian capital of Oslo, ambitious emissions targets (‑85% by 2030) are being met through shore-power systems in port and pilot floating solar installations. These platforms blend renewable generation with lower port emissions and improved livability. Oslo is also exploring a zero-emissions port and testing hydrogen-powered marine vessels to complement port electrification.

Indo-Pacific: The Rising Epicenter

Accounting for over 60% of global GDP and half of global trade, the Indo-Pacific is both a hotbed of maritime activity and a region under climate stress. Key opportunities include:

- Floating Offshore Wind: As fixed-bottom installations max out, floating turbines tap deeper waters. Wood Mackenzie forecasts the Asia Pacific (APAC) to lead in the energy transition, also underscoring that APAC’s geography and policy shifts will unleash floating-wind capacity. South Korea’s Ulsan region, Taiwan’s west coast, and Japan’s northern prefectures are positioning themselves as hubs for floating turbine production and servicing.

- Floating Solar: APAC, with strong solar irradiance and land limitations, dominates this market, which could reach US$2.73 billion by 2032. Programs in the Philippines and Pakistan leverage floating solar for water-saving and energy efficiency benefits. India’s National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) is rolling out over 1 GW of floating solar across reservoirs, while Thailand’s EGAT has launched 16 FPV projects to meet domestic clean energy targets.

- Multi-Use Innovation: Hybrid floating platforms integrating wind, solar, and aquaculture are emerging, especially in China. Projects are exploring fusing wind turbines, solar arrays, and fish farming on a single platform. Indonesia is developing floating cold-chain logistics hubs to connect island communities and reduce spoilage in seafood exports.

Regional governments are catalyzing change: Indonesia’s Makassar Strait development, Japan’s EEZ legislation, Taiwan’s investment-friendly policies, and South Korea’s demonstration projects all signal market maturation. All these developments commence as the economic stakes and strategic earning potential become clearer for stakeholders across public sector agencies and private sector enterprises.

Capital flows for APAC renewable investments could reach USD 1.1 trillion between 2025 and 2050. Offshore wind alone represents USD 621 billion, with USD 394 billion for solar PV—major opportunities for domestic manufacturing and services. Blue economy bonds, sovereign wealth funds, and blended finance instruments are increasingly targeting floating infrastructure to de-risk returns and channel climate-aligned capital.

In the realm of supply chains and jobs, localizing balance-of-system components such as anchor moorings, support vessels, and grid interconnections further captures value. The offshore wind sector in key Asian markets such as Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia represents a US$621 billion investment opportunity by 2050, with US$425 billion of this amount expected to be localized within the region.

Furthermore, within the maritime sector, there is a distinct opportunity of US$72 billion to US$97 billion for shipbuilding revenues specifically for the construction of offshore wind installation and service vessels, with most of this investment anticipated to be sourced regionally.

There are also innovation & ecosystem benefits. Artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics are revolutionizing offshore maintenance, while hybrid platforms deliver ecosystem advantages—fish aggregation, water conservation, and modular urbanism. Floating mangrove restoration systems and wetland agriculture pilots are being explored to regenerate degraded coastlines while supporting livelihoods.

Yet there remain technological challenges, in addition to factors that enable these developments:

● Technical Complexities: Designing safe, durable floating structures and multi-use platforms requires engineering R&D and ecosystem assessment frameworks.

● Regulatory Infrastructure: Coordinated policies across maritime zoning, permitting (EEZ regimes, environmental standards), and licensing are essential. Legal clarity around water rights and taxation will be critical.

● Financing Structures: Early-stage projects need blended finance, blue economy bonds, and de-risked loans to unlock commercial-scale capital. Development finance institutions and export credit agencies will play a vital role.

● Capacity Building: Maritime cities must invest in skills, ports, supply chains, and cross-sector coordination to fully capitalize on floating infrastructure growth. Regional cooperation among ASEAN, the Pacific Islands Forum, and BIMSTEC could accelerate shared frameworks and training.

Looking Ahead

The floating economy is approaching a pivotal moment. From scattered pilots to integrated city- and region-level deployment, the sector is entering an era where

● Coastal metropolises expand via floating districts calibrated for resilience.

● Energy systems rely on modular water-based platforms to deliver decarbonized power.

● Multi-use platforms knit together food, habitat, infrastructure, and culture.

● Global supply chains reorient toward marine-adjacent manufacturing, logistics, and services.

Maritime centers from Singapore to Rotterdam are not merely adapting but setting global standards. Meanwhile, Indo-Pacific economies have anchored a unique opportunity to pioneer floating infrastructure, industrialize green supply chains, and build climate-adaptive, equitable development models.

For investors, engineers, cities, and communities, the floating economy is no longer a speculative concept. It is a practical, high-growth domain that is gaining momentum and reshaping how society builds above, across, and within water. The race is on to anchor prosperity on the waves.