The planet Venus is like Earth’s worst twin – roughly the same size but with a thick layer of acid clouds over a crushing, hellish atmosphere. Its clouds in particular have been a source of interest, but it is difficult to understand how they change long-term: most missions around the planet don’t last long. New observations might have finally filled that gap in knowledge, thanks to weather satellites orbiting our planet that caught a glimpse of Venus accidentally.

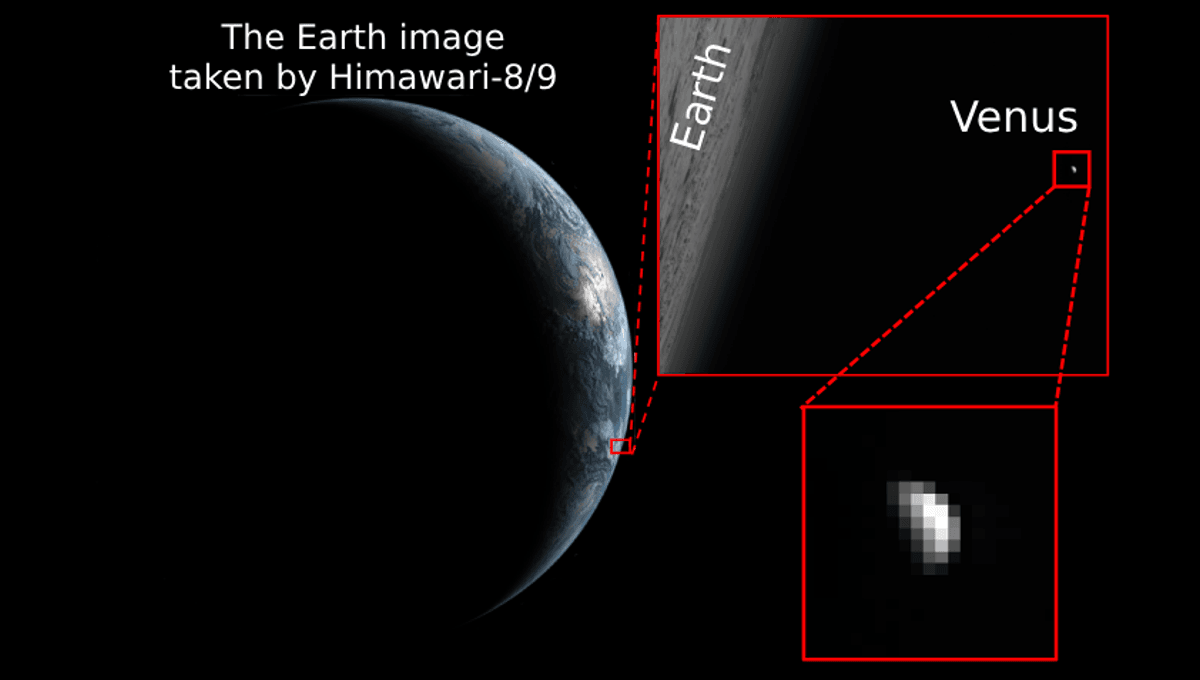

The Himawari-8 and -9 satellites, launched in 2014 and 2016, are Japanese meteorological satellites. They were designed to study global atmospheric phenomena, something that they do well thanks to a particular type of instrument: multispectral Advanced Himawari Imagers (AHIs). This device can – when the alignment is right – capture Venus just at the edge of Earth.

A team from the University of Tokyo, led by visiting researcher Gaku Nishiyama, realized that the instrument would be able to measure variation in the temperature on top of the Venusian clouds. They collected data from 2015 to 2025, providing crucial monitoring of the nearby rocky planet.

“The atmosphere of Venus has been known to exhibit year-scale variations in reflectance and wind speed; however, no planetary mission has succeeded in continuous observation for longer than 10 years due to their mission lifetimes,” Nishiyama said in a statement. “Ground-based observations can also contribute to long-term monitoring, but their observations generally have limitations due to the Earth’s atmosphere and sunlight during the daytime.”

The team was able to find 437 occurrences of the alignment in total, and they were able to show that temperatures did indeed change across the 10 years. Such methods will be very useful for continuous monitoring of Venus before future missions get there, though, while the European EnVision mission to Venus is still scheduled for the next decade, NASA’s two missions to Venus are in jeopardy following the Trump administration’s cuts.

“We believe this method will provide precious data for Venus science because there might not be any other spacecraft orbiting around Venus until the next planetary missions around 2030,” said Nishiyama.

It might not just be a tool for Venus either. The team believes that they can use accidental photobombs in weather satellites to study other worlds of the Solar System. The advantage of orbital observations is the lack of atmosphere, which affects what we can do from the ground.

“I think that our novel approach in this study successfully opened a new avenue for long-term and multiband monitoring of solar system bodies. This includes the moon and Mercury, which I also study at present. Their infrared spectra contain various information on physical and compositional properties of their surface, which are hints at how these rocky bodies have evolved until the present,” added Nishiyama.

The study is published in the journal Earth, Planets and Space.