For centuries, people thought Uranus was just a faraway star. It wasn’t until the 1700s that we realized it was a planet, one unlike any other in the solar system.

Even today, this icy, ringed oddball continues to keep scientists guessing. Uranus spins sideways, so each pole gets blasted with sunshine for 42 years straight. And its rotation is backward compared to most of its planetary siblings, except for Venus.

But the real puzzle? Uranus appears to be significantly colder inside than expected.

Back in 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 flew by and took a single direct measurement of its internal heat. Since then, researchers have believed Uranus lacks the heat that other giant planets have. And that’s a head-scratcher.

Foremost X-rays from Uranus Discovered

“We’re still trying to figure out why,” says NASA scientist Amy Simon. “And it’s tricky, because all our theories are based on just one piece of data.”

Using advanced computer modeling and revisiting years of data, NASA’s Amy Simon and her team discovered that Uranus does generate some of its heat. It’s subtle, but it’s there.

Scientists figured this out by comparing the energy Uranus absorbs from the Sun to what it emits back into space. The imbalance usually reveals a planet’s internal heat source. And it turns out that Uranus isn’t just a chilly mirror; it’s quietly radiating warmth, just a little less than its planetary cousins.

This tweak reshapes theories about the planet’s age, formation, and evolution. And perhaps most importantly, it proves that even the coldest mysteries can thaw with a fresh look.

Astronomers have detected X-rays from Uranus for the first time

“We thought, ‘Could it be that there is no internal heat at Uranus?’” said Patrick Irwin, the paper’s lead author and professor of planetary physics at the University of Oxford in England. “We did many calculations to see how much sunshine is reflected by Uranus, and we realized that it is more reflective than people had estimated.”

To understand how much heat Uranus truly generates, scientists needed to examine the planet’s full energy budget: how much sunlight it absorbs, how much it reflects, and how much it emits as heat.

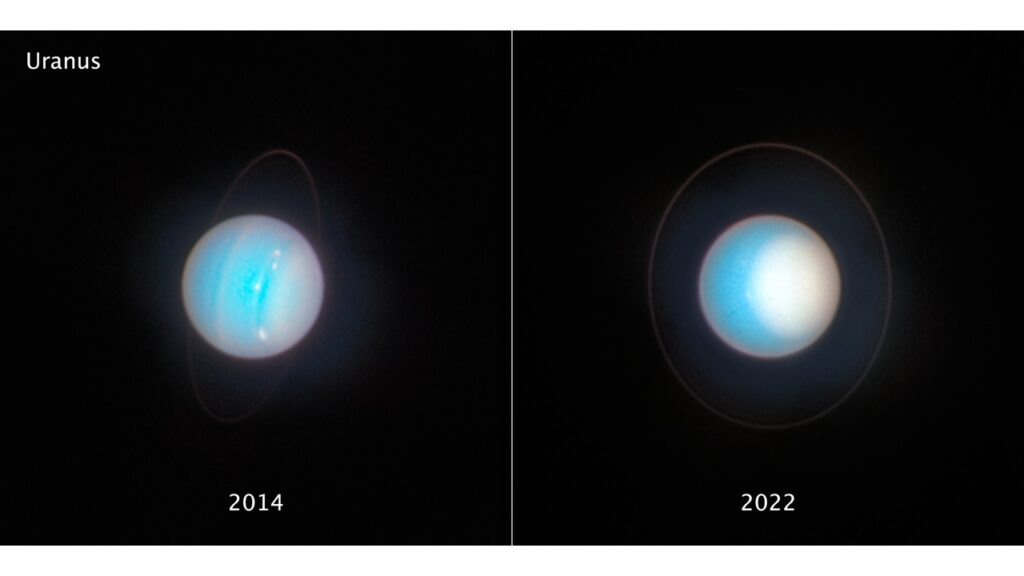

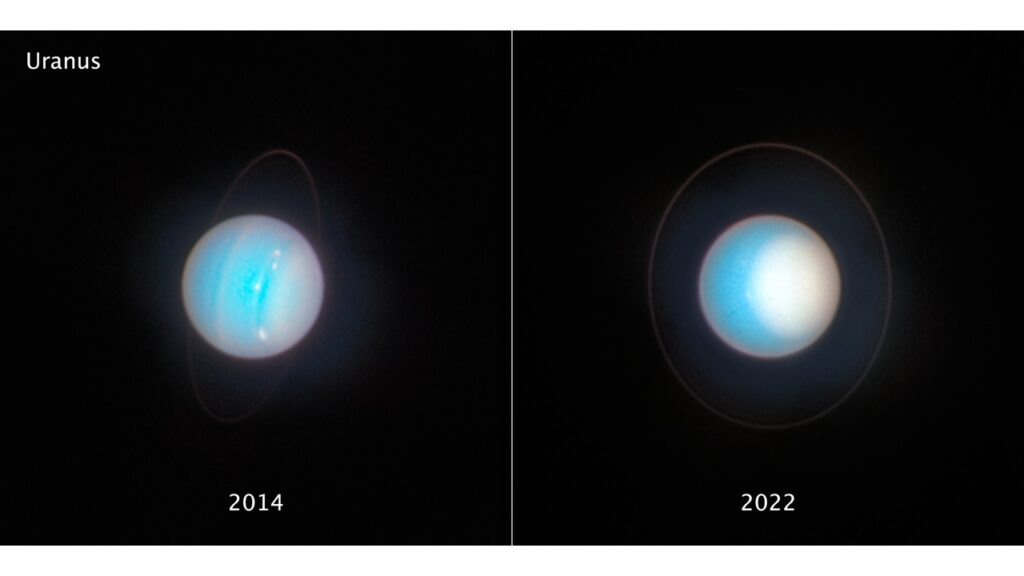

Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, A. Simon (NASA-GSFC), M. H. Wong (UC Berkeley), J. DePasquale (STScI)

But here’s the twist: measuring this isn’t as simple as looking straight at the planet. “You need to catch the light bouncing off at all angles,” said NASA’s Amy Simon, like tracking glitter in a disco ball, not just the flash in your face.

Oxford researchers built a highly detailed computer model, stitching together decades of sky-gazing data from Earth and space, including data from NASA’s Hubble and its infrared telescope in Hawaii.

NASA’s Hubble and New Horizons set their sights on Uranus

Their model captured everything: hazy skies, shifting clouds, and seasonal shifts, all the quirks that affect how Uranus handles sunlight and heat. The result? The sharpest look yet at the energy game this sideways-spinning, icy giant is playing.

New findings show that Uranus quietly radiates about 15% more energy than it gets from the Sun. It’s not as toasty as Neptune, which gives off more than twice what it absorbs, but it’s enough to prove Uranus has its internal heat source.

So what does that warmth mean?

Scientists like Amy Simon want to delve deeper into why Uranus still retains some of its ancient heat and what that reveals about its tumultuous past. From its sideways spin to mysterious cooling, Uranus has always been the oddball in the solar family.

However, studying it isn’t just about decoding one planet’s story; it also helps researchers understand how and when planets formed, shifted orbits, and even how distant exoplanets (many of which are Uranus-sized) might behave today.

Journal Reference:

- Patrick Irwin, Daniel Wenkert, Amy Simon, Emma Dahl, Heidi Hammel. The bolometric Bond albedo and energy balance of Uranus. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staf800