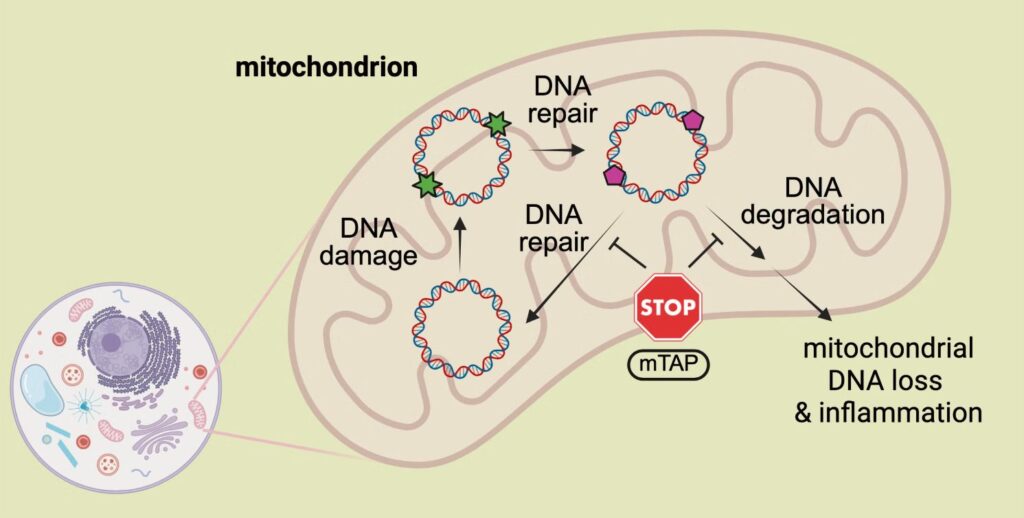

Inside each cell, mitochondria aren’t just energy factories; they carry their little instruction manual: mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). This mini-genome keeps the cell’s engine running and helps sound the alarm when danger strikes, like inflammation or stress.

But mtDNA is vulnerable. Genotoxic stress, damage caused by factors such as radiation or chemicals, can erase parts of it, and currently, there’s no chemical fix to prevent that loss until now.

Researchers at UC Riverside have unveiled a new chemical tool- mitochondria-targeting probe (mTAP)- designed to shield mtDNA before it breaks. By preserving these tiny strands of life, the tool could help protect cells from spiraling into disease.

When cells get stressed, mtDNA doesn’t fix itself like nuclear DNA. Instead, it slowly unravels. As those multiple copies degrade, the ripple effects can be severe: compromised tissue, inflammation, and potential disease.

However, science now has a clever countermeasure.

Study demonstrates impact of temperature on mitochondrial DNA evolution

This newly developed chemical probe not only repairs mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) but also protects it from damage. Like a guardian, it identifies damaged spots and prevents the cellular cleanup crew from erasing them. The result: less DNA loss and greater cellular stability.

The magic lies in its design: One part latches onto broken mtDNA, while the other delivers it precisely to the mitochondria, leaving your nuclear DNA untouched.

In lab tests as well as studies using living cells, the probe significantly reduced mtDNA loss after lab-induced damage mimicking exposure to toxic chemicals such as nitrosamines, which are common environmental pollutants found in processed foods, water, and cigarette smoke. In cells treated with the probe molecule, mtDNA levels remained higher, which could be critical for maintaining energy production in vulnerable tissues such as the heart and brain.

Mitochondrial DNA, although small, plays a crucial role in maintaining cell health. When it breaks down or escapes into the cell, it doesn’t quietly vanish; it shouts. These fragments can trigger immune alarms, linking mtDNA loss to diseases ranging from diabetes and Alzheimer’s to arthritis and gut inflammation.

Mitochondrial DNA can be inherited from fathers, not just mothers

That’s what researchers at UC Riverside discovered with their new chemical shield. They worried tagging mtDNA might block its function. However, against expectations, the treated DNA still played its genetic tune, transcription continued, and the machinery that turns DNA into proteins remained functional.

The project builds on more than two years of research into the cellular mechanisms that govern mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) processing. While additional studies are needed to explore clinical potential, the new molecule represents a paradigm shift.

“This is a chemical approach to prevention, not just repair,” Linlin Zhao, UCR associate professor of chemistry, who led the project, said. “It’s a new way of thinking about how to defend the genome under stress.”

Journal Reference

- Dr. Anal Jana, Yu-Hsuan Chen, Dr. Linlin Zhao. Mitochondria-Targeting Abasic Site-Reactive Probe (mTAP) Enables the Manipulation of Mitochondrial DNA Levels. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. DOI: 10.1002/anie.202502470