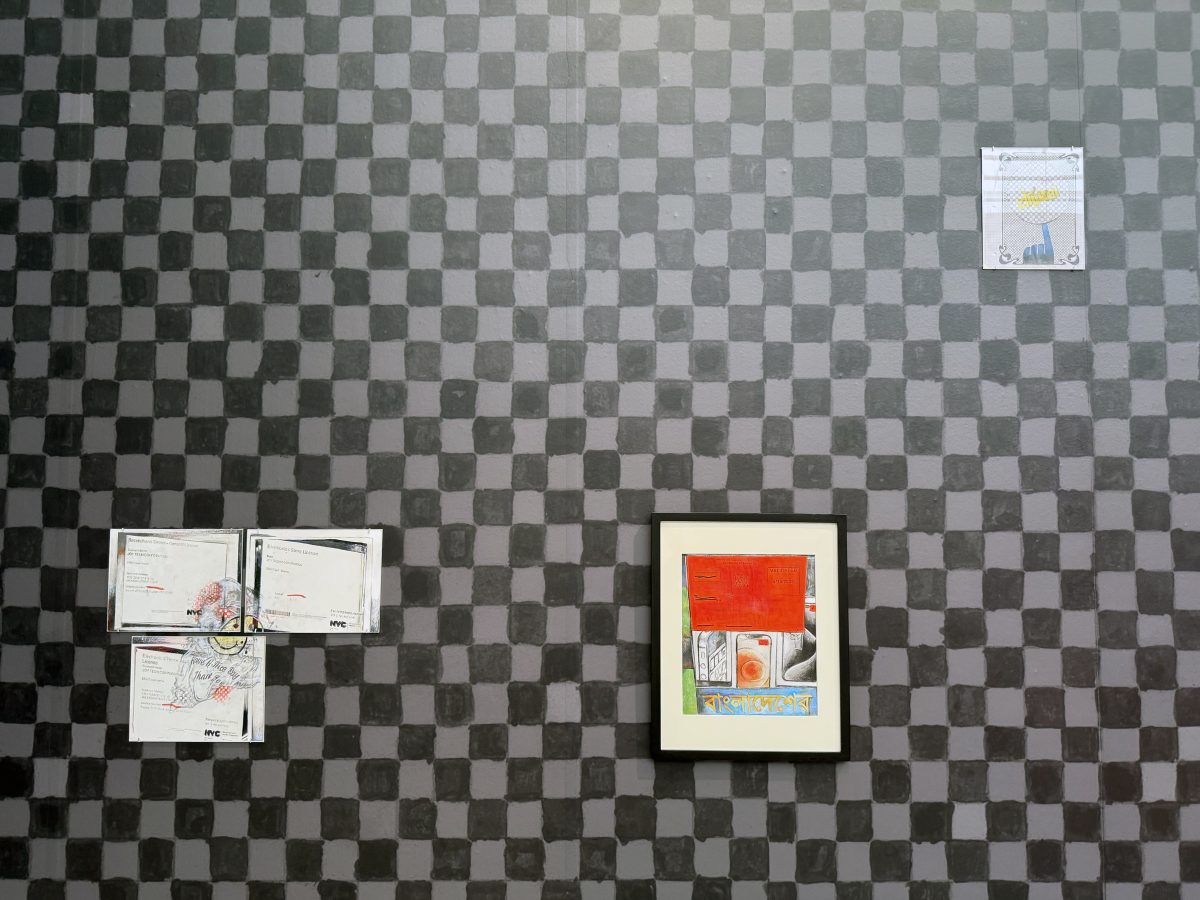

The For You page, as the popular TikTok comment goes, is getting too local. I, for one, am grateful. Umber Majeed’s exhibition J😊Y TECH draws from the visual vernacular of phone repair stores in the Jackson Heights neighborhood of Queens — their densely packed cacophony of bright colors, screaming fonts, and many languages spilling out into the sidewalks — as an extension of her ongoing Trans-Pakistan research project inspired by her uncle’s now-defunct tourist agency. She builds his real-life business into a digital universe through augmented reality (AR), video, drawings, and ceramics that mine “South Asian digital kitsch,” as the introductory text puts it. Though its execution is a bit uneven, this one-room exhibition is one of the most technically inventive I’ve seen, and is a fresh and exciting excavation of the fertile physical/digital intersection between diasporic Asian and early internet aesthetics.

Technological nostalgia, particularly around the 1990s and early 2000s, is a persistent visual theme throughout the exhibition even as its own tools are cutting-edge. One of the first works that viewers encounter is “Untitled” (2025), a one-minute single-channel video on a special display that produces a convincing simulation of a three-dimensional box. Objects float mesmerizingly, as if in an aquarium or on a 3D screensaver. These include a hand-drawn red-and-white checkered Apple logo that is something like an emblem for the exhibition; relics of data storage like a CD-ROM and a floppy disk; and a Mughal dome that bops around like a jellyfish. The box itself works almost like a meta data storage device — not one that stores raw bits of information such as matrices, arrays, or graphs, but something more like a repository of collective memory.

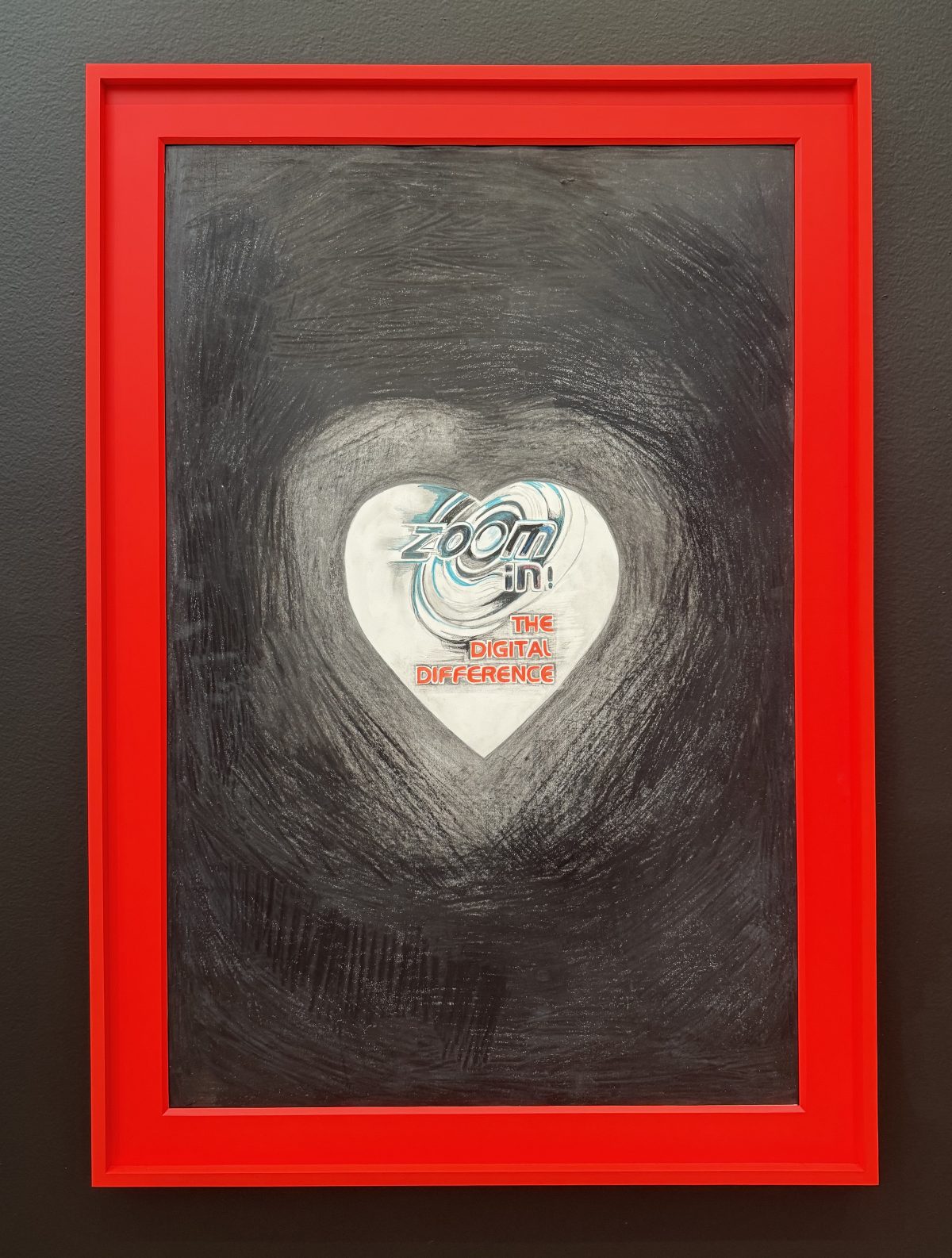

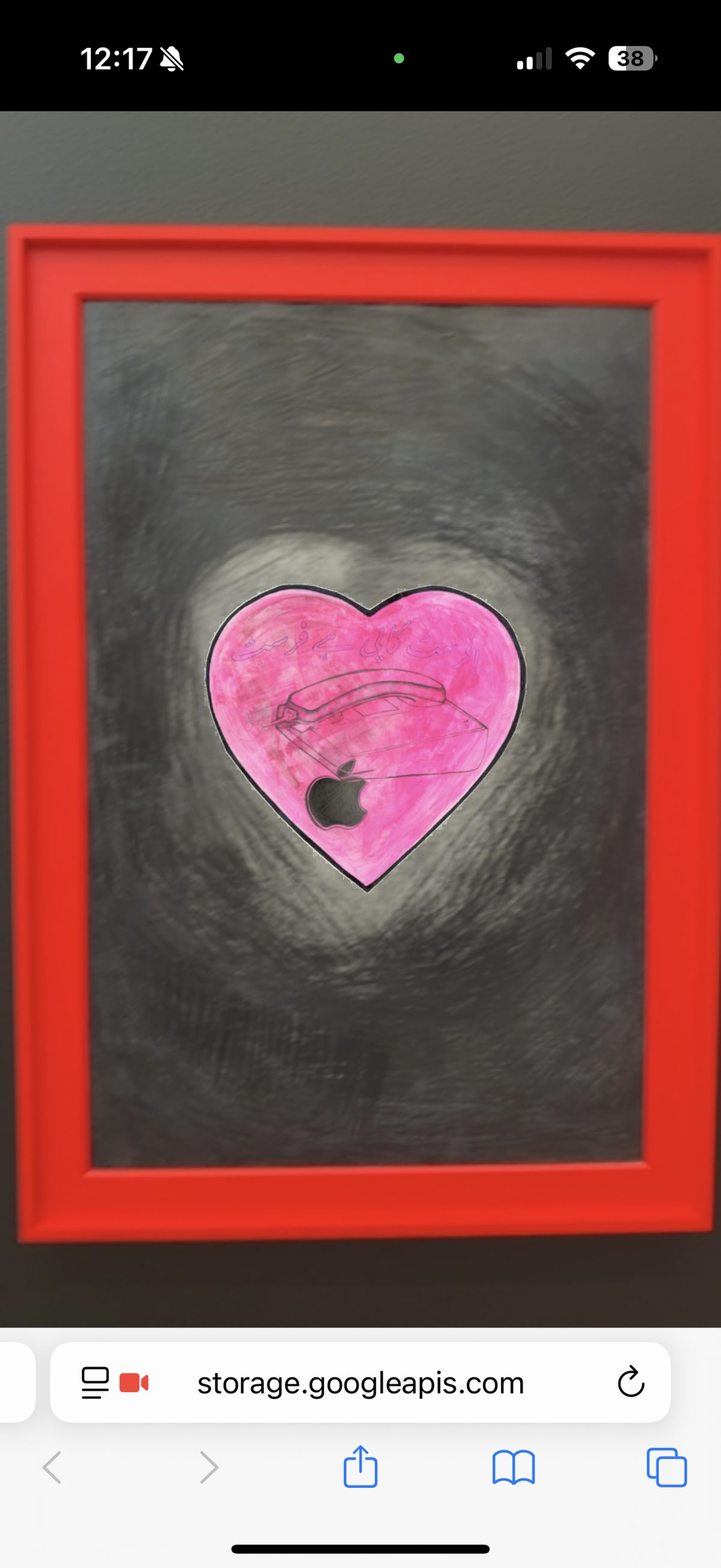

Multiple works in the exhibition contain AR elements, two of which are displayed across from “Untitled.” The drawing “zoom in” (2024) consists of the titular words along with the phrase “THE DIGITAL DIFFERENCE” embedded in the center of a heart, surrounded and engulfed by lines of motion that recall Y2K Futurism. The words take on a double meaning: On the one hand, “zoom” denotes speed and excitement, in line with a tourist agency promising adventure; on the other, it suggests digitally zooming in on something, which emphasizes the distinctly handmade quality of the work. Follow a set of instructions on the wall label and point your phone toward the drawing, though, and the heart beats with serial animations that includes logos, arrows, and a map that references the 1947 partitioning of India, and what would become Pakistan and Bangladesh.

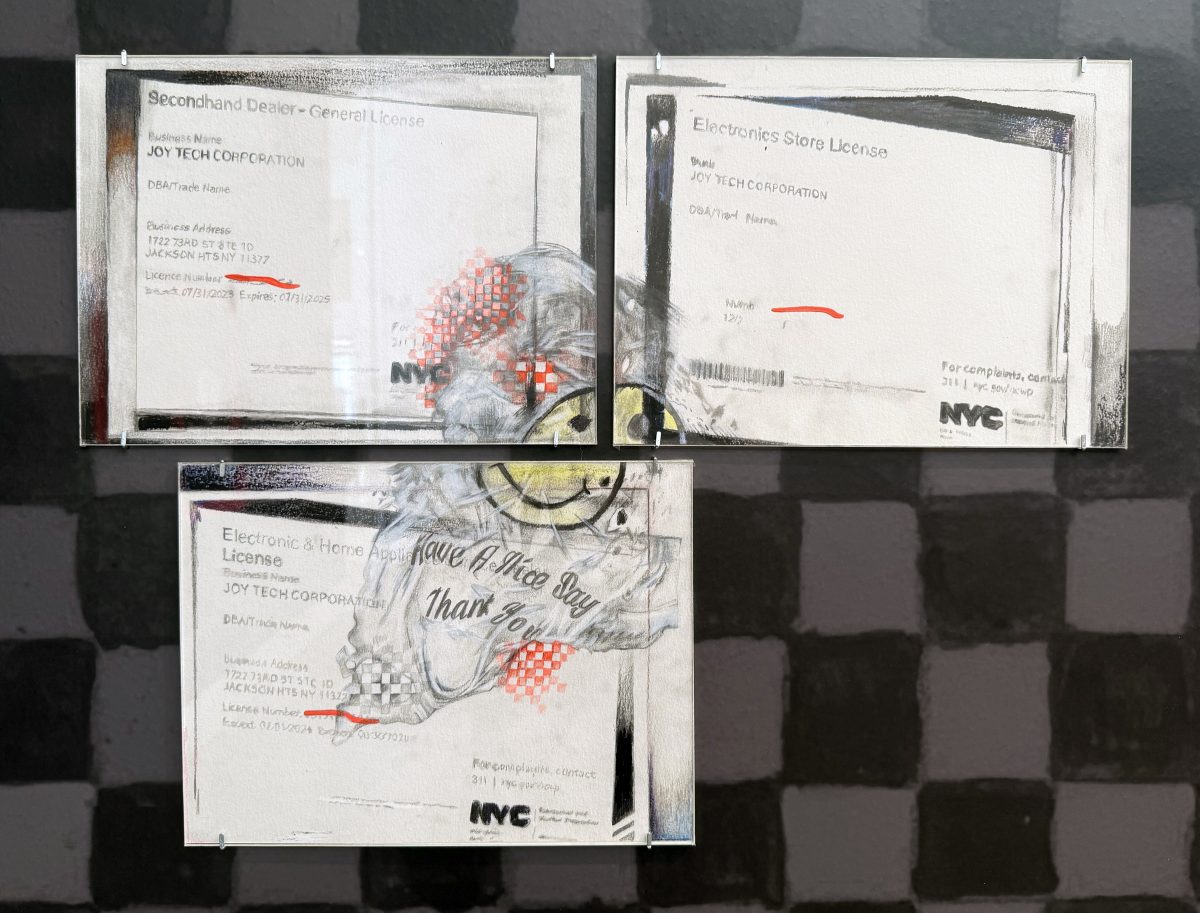

J😊Y TECH toys with and occasionally explodes the typical form and boundaries of an exhibition. The bold neon-red frames of the AR works color more analog elements as well, including a dynamic arrow that zig-zags from the ceiling onto the top of the partial wall that divides the exhibition diagonally and down its side, ending on the floor pointing toward the massive vinyl wall work “Timeline” (2024–25). A black and white, red and white, or gray and white grid alternatively invoking the tiled flooring of a small business and a blank digital space (such as in a new Photoshop document) is a key motif of the exhibition — it appears on multiple walls and is reproduced in smaller, more playful form within individual works, such as a vortex sucking in an older-generation iPhone. The motif is intended to bend and fuse the planes of real and digital space just as she digitally builds on her uncle’s real-life travel agency.

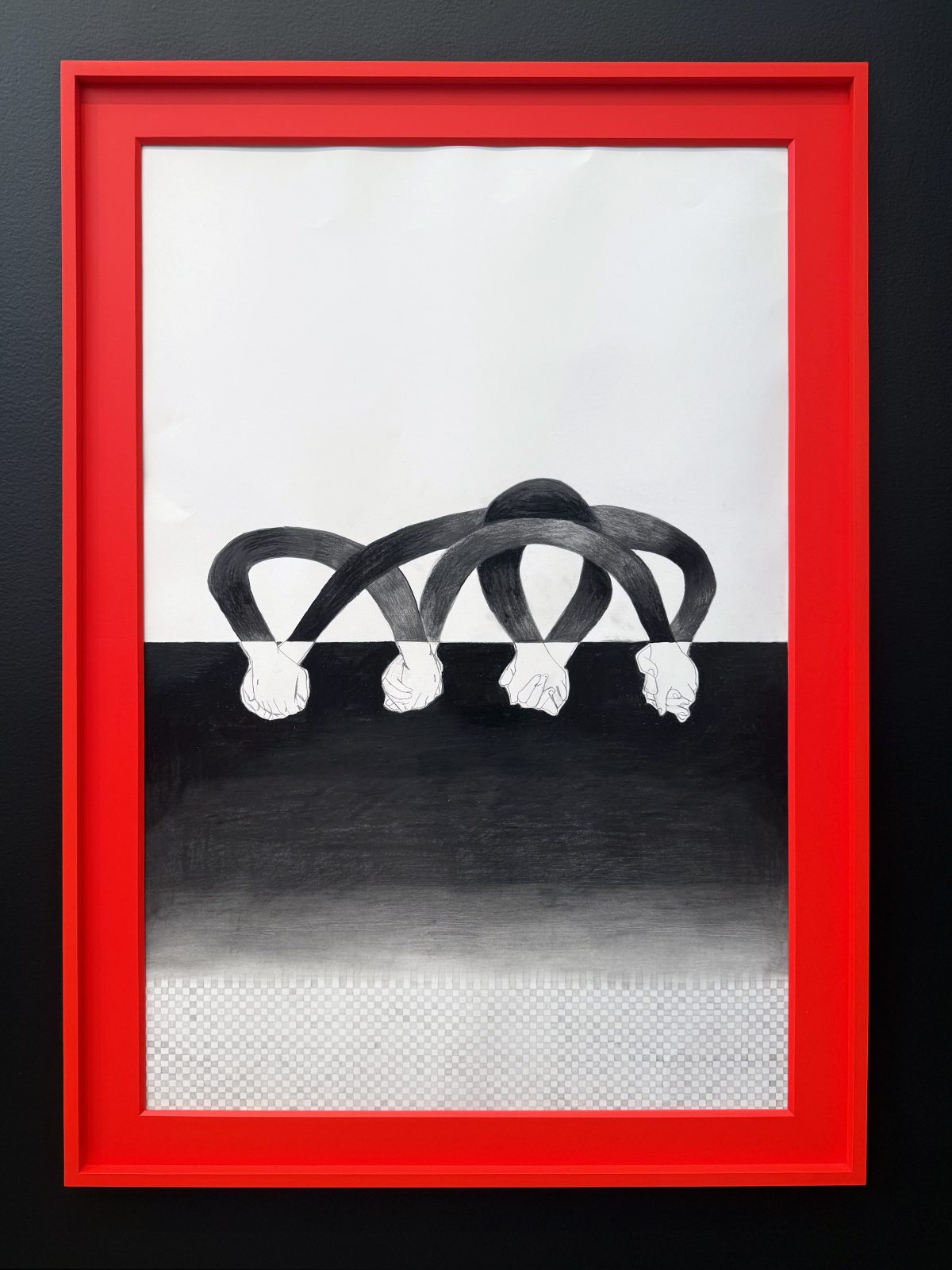

animation; right: Umber Majeed, “Saath Haath” (2024), mixed media on paper and web-based augmented reality animation

Still, it can sometimes feel like the ideas in this exhibition can supersede their execution. Though she intentionally and effectively privileges those with the language and/or culture she’s targeting — those who read Bangla and Urdu would recognize words in those languages in the aforementioned untitled animation, for instance — some works demand a lot of viewers regardless of their background. While you might recognize the Mughal dome that also floats around the same work if you’re familiar with South Asian culture or art history, you might not know it sat atop the Pakistan pavilion at the 1964–65 World Fair unless you’re listening to the Bloomburg Connects audio description or reading its transcription. Other pieces are inaccessible in spatial ways: Certain drawings, such as “Goes Digital” (2021), are hung inhumanly high, and therefore difficult to see.

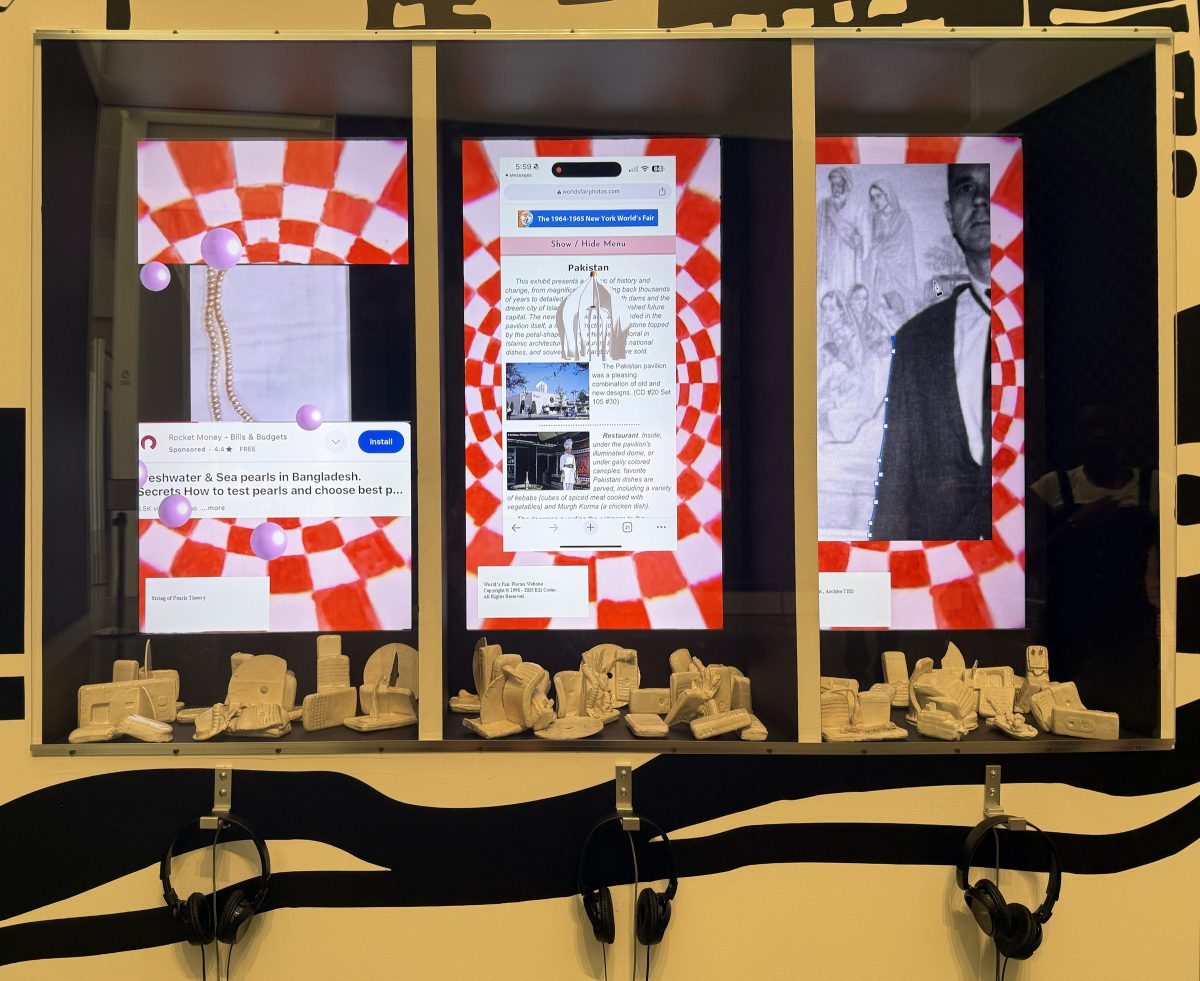

An untitled video work near the end of the exhibition feels most difficult to grasp. It mimics the visual-sonic-informational overload of social media — there’s image-editing, ads, webpages, archival information, iPhone screen recordings, and icons bouncing about the three channels, not to mention a collection of real-life ceramic sculptures. It effectively satirizes the kind of quick-cut brainrot endemic to Youtube essays and TikToks, but to what end? I walked away with a lot of interesting information buzzing around my head — jewelry designer Barbara Anton was commissioned to highlight the natural pink pearl farming industry in what is now Bangladesh as part of the World Fair, and “String of Pearls” is also a term invented by the United States to refer to a network of Chinese military and commercial facilities, for instance — but not the architecture to put it together.

Majeed’s work also spurred perhaps the deepest and most substantive episode so far in my ongoing struggles with my perception of “good” and “bad” aesthetics, and whether they come from an internalization of problematic hierarchies. I loved “WE CAN FIX IT” (2025), a wonky signboard made of decals on ceramic and wood that bears the title along with faded photos of defunct devices. It felt like a smarter, sharper, and more politically agitative version of the work of Shanzhai Lyric. Rather than simply arguing for the beauty of pedestrian culture, as Shanzhai Lyric does with misspelled English words in Chinese clothing and Majeed does with diasporic South Asian-owned tech repair shops, the work also points toward the potential of these visual languages to unsettle dominant forms. To me, they represent the trickle-up of hyperlocal rather than the trickle-down of corporate culture, the evidence of life carved out from inhospitable terrain. But I also wondered if I responded to the work because I could easily imagine it in a white cube gallery.

I also wondered if someone who was less familiar with the visual culture of Queens and invested in the related Chinese/Chinese diasporic aesthetic of Shanzhai may have a differing opinion of “WE CAN FIX IT.” And I considered whether a related bias in background (such as my own failed forays in the medium) might shape my feelings about her drawings. Some, such as the AR-activated “Saath Haath” (2024), depicting hands clasped together beneath a horizon line as dark bands connect them above, felt a little juvenile to me in their technical clumsiness, whether intentional or not. But they do make for a great contrast with the slickness of the exhibition’s digital innovation, as well as mesh well with the stuttering visual culture of an early internet, which is endearing and nostalgic.

J😊Y TECH cuts particularly deep for a generation of Asian Americans who came of age during the 1990s and 2000s, and saw the aesthetics of their diasporic culture meld, sometimes queasily, with that of early digital culture. Majeed’s work might be the first time I’ve really encountered a meaningful exploration of that idea, which brings with it the baggage of all that cultural anxiety, as well as excitement. I can’t wait to see where Majeed — and the rest of the vanguard of this particular niche where first-gen diaspora meets early-gen tech — goes next.

Umber Majeed: J😊Y TECH continues at the Queens Museum (Flushing Meadows, Corona Park, Queens) through January 18, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Lindsey Berfond.