99% Invisible Presents: A Quiet Storm Party w/ DJ Ayanna Heaven

Join us for an in-person 99PI event celebrating Quiet Storm. There will be drink specials, show swag, and dope music.

When: Sunday, July 27th, 5-8 p.m.

Where: Ace Hotel- Downtown Brooklyn, NY

In the mid-1970s, the national media was reporting on the rise of a new socioeconomic group that was quickly gaining unprecedented access to jobs, education, backyard swimming pools – the good life.

Journalists seemed fixated on what many were calling the “new black middle class”. The stars of the moment were regular, ascendant black Americans.

“We were dealing with people that were having economic stability for the first time in generations,” says writer and cultural critic Craig Seymour. “The black middle class of the 70s was really kind of reaching the world with arms wide open and trying to just have new opportunities and new experiences, and it’s just not been afforded to masses of black people before that.”

And as these new masses were figuring out what upward mobility felt like, they were also exploring what black middle class-ness sounded like. “It was the aspiration to expand, to seek out new types of sound, new sonic adventures,” Seymour says.

In the previous decade, some of the biggest songs in black popular music had been dancey, sometimes political – and heavy on the funk.

But by the mid 1970s, that new generation of black Americans was gravitating to a much more mellow sound – a sound that matched the soft life of their middle class dreams. They wanted music that was smooth and easy, and all about love and romance.

And at a small black college radio station in Washington DC, a show called “The Quiet Storm” would give them exactly what they were looking for.

The show’s concept was pretty straightforward: an evening program featuring hours of mostly uninterrupted soulful ballads and love songs.

That simple format made The Quiet Storm an overnight sensation. And as the show became a fixture in homes and on car stereos throughout black DC, it also set off a debate over how black music should sound, and what it should say.

The show was started in 1976 at Howard University, which had just acquired its radio station WHUR (which stood for Howard University Radio) 5 years earlier.

RaEdits, CC BY-SA 4.0

This was the first black-owned radio station in DC – a city where 3 out of four residents were black.

In those early years, WHUR began pursuing an upscale commercial market. DC’s black middle class was thriving, and WHUR hoped to develop programming that could attract those listeners and draw ad revenue.

As part of that new mission, WHUR hired Cathy Hughes as station manager. She began thinking about how to make music shows to attract new listeners to the station. She decided to survey the people closest to her.

“She was looking at her girlfriends,” says music critic Eric Harvey “Who was she hanging out with? Upwardly mobile, single black women who were being completely underserved by popular radio.”

Cathy realized that a local show that appealed to single, professional black women could be really popular, and a great source of ad revenue. So she began to loosely conceive of a weekend evening show focused on romantic music – slow, soulful R&B ballads and very smooth love songs.

“She thought, ‘well, hey, who doesn’t want to be serenaded?’”, says cultural critic Craig Seymour. “‘Who doesn’t want to have somebody play love songs to them and talk in a deep voice?’ So she kind of tailored the show to that particular audience.”

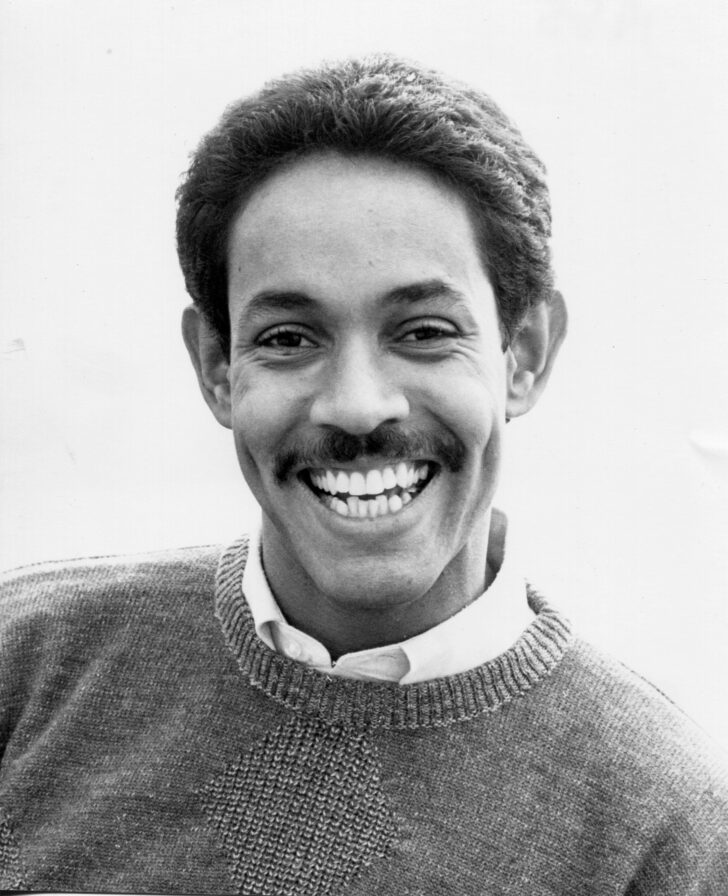

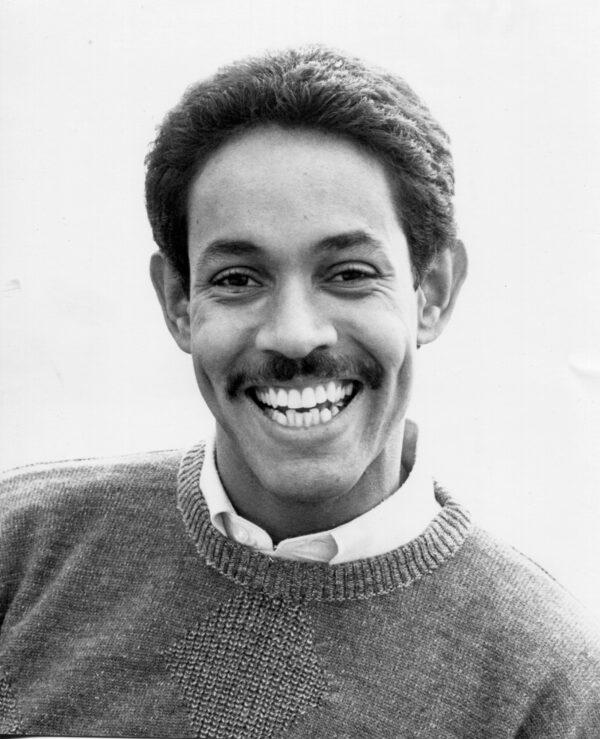

According to one version of the show’s origin story, Cathy tried out a few different DJs for her nascent show, before she eventually settled on an intern named Melvin Lindsey, who also babysat her son.

Although Melvin was not Cathy’s first or favorite choice for the DJ gig, he was the one who would soon take her idea and make it a huge success.

Melvin was a handsome, buttoned down kid from DC, known for carrying a briefcase around campus. He could also be shy and softspoken.

And that quietness is what set Melvin apart immediately the night he hosted his first show in May 1976.

That’s because Melvin represented a new kind of on-air personality.

The previous generation of black radio DJs were super performative, flamboyant and rambunctious.

Melvin mellowed that profile way out. When he spoke, he was so gentle and fluid, and it all seemed just effortless.

“Warm, inviting, engaging – that was his style. His style of radio made you feel like he was talking directly to you. That’s a big achievement,” says Dyana Williams, who was one of WHUR’s first DJs and a mentor to Melvin Lindsey. “He had the voice. He had the composure. He was humble. It was like a chef, like he prepared this great, soul satisfying meal.”

WHUR had never done a show that sounded like this. Up to that point, the station had mostly been a mix of public affairs programming, and a lot of jazz. Definitely not b-side baby making music.

Listeners were caught totally off guard. On the night of the first broadcast, Melvin was flooded with calls from people requesting their own favorite slow jams. Others phoned in just to show the young DJ some love. For the next two days – WHUR’s switchboard filled up with listeners calling in from all over the DC area, asking about that new show.

Together, Cathy Hughes and Melvin Lindsey – the intern-student-babysitter – had just created a hit.

Cathy decided to name the new show “The Quiet Storm,” after Smokey Robinson’s extremely sensual, suggestive hit single “A Quiet Storm.” Cathy told Melvin she liked the name because it had “subliminal seduction in it.”

The Quiet Storm show started in 1976. By the end of the next year, it was the number one weekend music show in Washington. It was so successful, Cathy expanded it to weeknights, which made WHUR the second highest rated FM station in DC. And it brought in millions in ad sales.

The Quiet Storm’s sudden and wild popularity came in part thanks to Melvin’s innovation as a curator. Instead of going for the uptempo jams, he chose… softer tracks, the smooth soul, the romantic ballads.

As a grassroots-oriented station, WHUR had its own history of freeform programming, where DJs let the music sprawl.

Melvin and Cathy’s innovation was the way they took that freeform approach, and applied it to a new kind of music – slow jam deep cuts.

“Throughout the day’s programming – starting with morning drive until afternoon drive – you got music that was keeping you up and going, more up-tempo music,” Dyana Williams remembers.

“But then that stopped when it got dark and you were not working and you are not driving and you had finished dinner and homework with the kids and you’re lighting your candle – and maybe more – and chilling. And what you were hearing were mid tempo and ballads that were about love.”

Melvin seized on a major shift that was happening in the late 1960s and early 70s, as black groups began experimenting with a whole new kind of sound.

“It starts with the artists making these sort of… I don’t want to say “slicker” in a bad way, but just kind of these more sophisticated – musically sophisticated types of popular music,” says Craig Seymour.

Popular soul and R&B was starting to expand from the shorter, more jerky dance funk tunes of the previous era. Artists were smoothing the edges, making songs longer, and bedazzling their tracks with big, rich string sections.

“This (was) modern, elegant, soft, romantic edge to popular soul music that artists were expanding upon in the early 1970s,” says Eric Harvey.

One thing that was driving this expansiveness was the influence of soundtracks for black-themed films like Shaft, Trouble Man, and Sparkle.

This was beautiful, innovative music that adapted funk and soul to the openness, continuity and minor key moodiness of film scoring.

Black film soundtracks were having a major influence on R&B. And as more and more artists began replicating the lush, palatial sound of film scores, what emerged was a kind of smooth soul that would help define Quiet Storm.

So the music is changing. The ambition in the songs – the tracks are getting longer,” says music and culture critic Nelson George. “WHUR is one of those stations responding to that, in terms of what their playlist is, and the sound of the station.”

Although The Quiet Storm show had been aimed at the black middle class at first, it quickly transcended. If you walked through any of DC’s black neighborhoods in the evening, you could hear the radio show coming out of row house windows and the cars that drove by just as the sun was setting.

“When The Quiet Storm time came, it’s like the tempo just slowed down. It’s just so hard to explain,” remembers Craig Seymour, who grew up listening to The Quiet Storm in the DC area, “how a show could really just change the vibe of a whole city, or at least the black part of the city, at a particular time. It’s almost like a dimmer switch, where all of a sudden these ballads started coming in and just the whole vibe of Black Washington began to change, along with the moods of Melvin Lindsey.”

By the mid 1980s, WHUR’s “The Quiet Storm” had grown into something way bigger than the radio program that Cathy Hughes and Melvin Lindsey started in 1976.

The DC program had inspired 120 broadcasters around the country to develop their own shows – and sometimes even entire stations – just like the WHUR program. Those new shows were not affiliated with the original Quiet Storm, but a lot of these copycat programs nodded to it with names like “Sunday Night Cool Out,” and “Soft Touch”.

And the DJs were clearly imitating Melvin’s signature smooth style.

“There’s a lot more mellow voices. They tended to be either very low tone women or low baritone men. It’s really a profound aesthetic change,” says Nelson George. “It’s going from hard whiskey, to cognac.”

As Quiet Storm programming took off on black radio in the mid 80s, the quiet storm sound solidified into a brand new genre of music. Record companies saw this as a chance to sell a lot of music to the so-called “sophisticated Quiet Storm” audience, with disposable income. Record companies were even asking artists to make sure they had quiet storm-sounding cuts on their next albums.

Quiet Storm radio also launched full superstars – balladeers who fully embodied that smooth, mellow, romantic sound. No one saw more commercial success thanks to Quiet Storm radio than Anita Baker.

Her 1986 album “Rapture” was a Quiet Storm staple, with songs like “Same Ole Love” and “You Bring Me Joy”.

At the time, it was rare for a black musician doing adult R&B to have what was called a “crossover” album – one that went beyond Quiet Storm and other formats that were considered black radio, to find success with mainstream (that is, white) listeners.

But that’s exactly what happened with Rapture. The album was launched by Quiet Storm radio, and then crossed over to pop radio, expanding Anita Baker’s audience exponentially.

“To this day, Anita Baker can still sell out 5000 seat theaters, “says Eric Harvey. It’s hard to imagine Anita Baker’s stardom being half of what it is today without being nurtured in the quiet storm format.”

Although by the 1980s, quiet storm’s “smooth-pop-soul-love song” sound was blowing up on radio stations and in record stores all over the country – not everyone was feeling the love.

“There were lots of aesthetic criticisms about quiet storm music as well, which in some cases was deserved,” Eric Harvey says. Some music fans complained that quiet storm “music” wasn’t really music at all. More like mushy, tuneless versions of black America’s great funk, jazz, and soul traditions. “This is music that could easily be called by some critics, you know, sonic wallpaper, easy listening. For some people, it’s like what you listen to over the PA system at the mall.”

There was also the critique that quiet storm was so decidedly apolitical. To some, that was unusual for a form of black music as big and influential as quiet storm. This was the 1980s, a moment when black America was in the midst of multiple crises, especially with Reaganomics, crack cocaine and the war on drugs.

The way some listeners saw it, black music had a responsibility to capture the urgency of the moment. But quiet storm seemed to be abdicating black music’s historic role as the teller of truths about the hard realities of black life in America.

The last thing black folks needed was gushy love songs and apolitical muzak.

“It felt complacent, especially as Reagan took over and especially as the opportunities for African-Americans in the US started retreating back to a pre civil rights era,” says Harvey. “And here was Quiet Storm, just kind of encouraging people to be calm and stay home and be domestic.”

The gooey, apolitical, deeply unfunky sound of quiet storm had proven so successful, that by the mid 1980s it dictated what many major labels wanted from their black artists. Record companies had locked in on so-called “upscale urban audiences”, and the gates were all but closed to black music that didn’t appeal to those listeners.

Resentment was growing for Quiet Storm, which just felt more and more out of touch.

A new generation of artists and fans wanted something different from black popular music.

This was exactly when and why rap music, which was relatively new at the time, began to gather steam. In part, rap was a backlash against the softness and the gatekeeping that had swept through the music industry and across radio thanks in part to the dominance of quiet storm.

But even as hip hop took off in the late 1980s, Quiet Storm radio was still popular all over the country.

In 1985, Melvin Lindsey was lured away by WKYS – another black station serving DC, and a WHUR rival. As proof of Melvin’s star power, WKYS offered him a historic million-dollar, multi-year contract to replicate his old show under the new name “Melvin’s Melodies.”

Melvin had a huge career in radio and TV around Washington.

He was hosting a show on BET – until he became too sick to work. Melvin died of AIDS in 1992. He was 36 years old.

There are still Quiet Storm shows everywhere. And hip hop has long borrowed from quiet storm, with rappers from A Tribe Called Quest to Kendrik, Drake, Tyler, and MF DOOM invoking and even sampling freely from the smooth soul stars of the 70s and 80s.

You can also hear it in the music of today’s R&B and soul artists like Blood Orange, Frank Ocean, and Solange.