China’s recent announcement to further expand sectoral coverage and shift its national emissions trading system (ETS) from an intensity-based to an absolute cap approach by 2027 marks a pivotal moment for Asia’s largest carbon market.

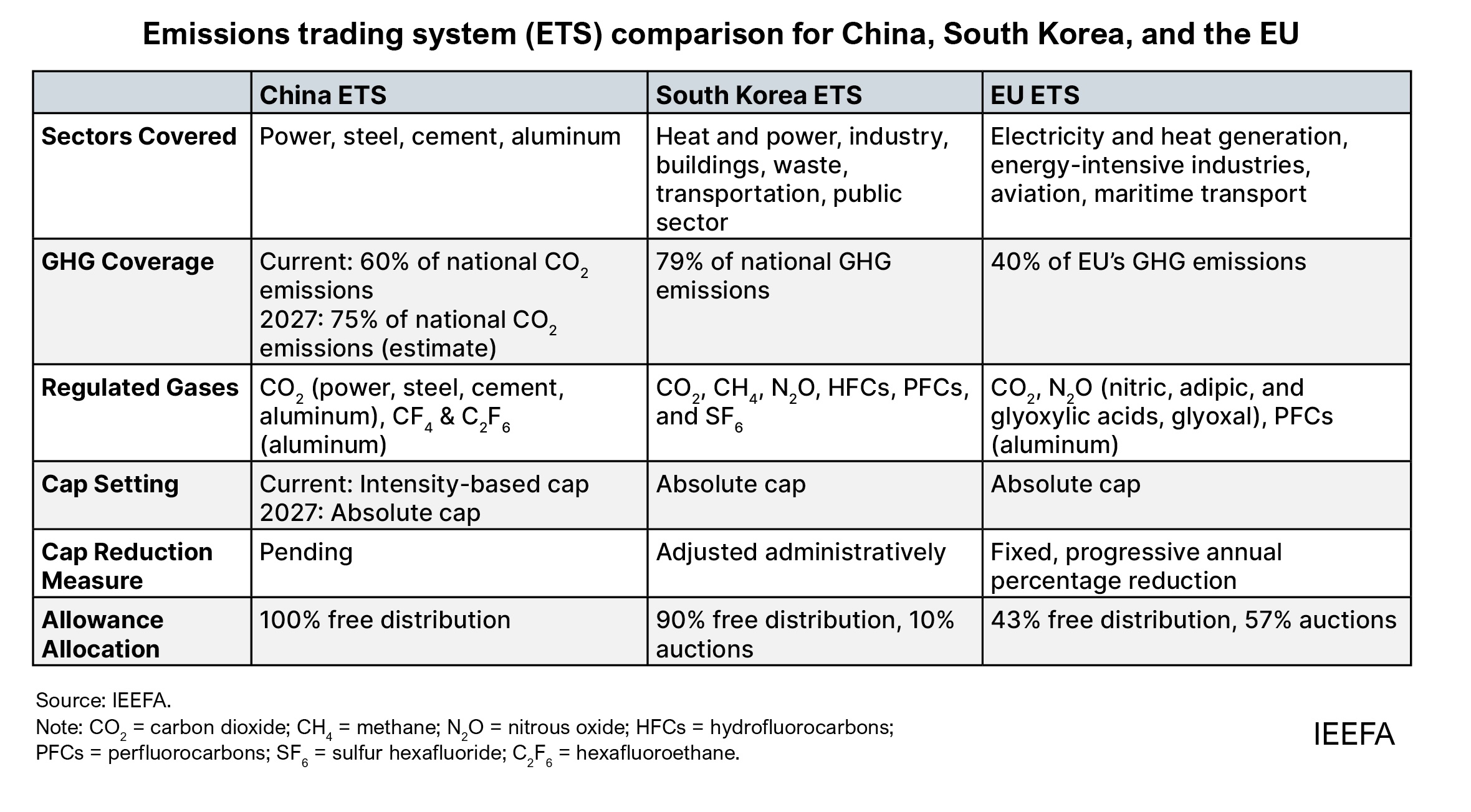

Evolving from pilot programs across eight provinces, China’s national ETS has been operational since 2021. It currently covers approximately 8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions — roughly 20% of total global emissions. Initially limited to the power sector, the ETS expanded this year to include steel, cement, and aluminum smelting, bringing 1,334 additional emitting entities under its scope and raising coverage of the country’s total carbon emissions from 40% to 60%. The expansion also broadened the system’s scope beyond CO2 to include the regulation of tetrafluoromethane (CF4) and hexafluoroethane (C2F6) emissions from the aluminum sector. The inclusion of other major emitting industries by 2027 is likely to further expand national coverage and regulation of gases.

The significance of absolute caps and higher carbon pricing

The shift to absolute caps is an important step in aligning China’s ETS with international best practices. Absolute caps underpin mature systems, such as the European Union’s (EU) ETS, which helped reduce carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions from 4.6 billion tonnes in 2005, when it was first introduced, to 3.2 billion tonnes in 2024. The decline in emissions intensity is steeper, as the EU’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is significantly higher in 2024 compared to 2005.

Unlike the intensity-based approach that allows for increasing emissions alongside output, an absolute cap imposes a fixed ceiling on permitted emissions, exerting stronger pressure to adopt clean technologies or bear higher compliance costs. Markets that initially favor intensity targets to safeguard economic growth and ease early adoption should therefore transition to an absolute caps system to achieve meaningful emission reductions. China will begin its transition with major industries that have stable emissions starting in 2027, with full implementation by 2030.

A recent report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) assessed the current state of carbon pricing in Asia, highlighting that substantially higher carbon prices are needed to drive notable decarbonization. With regional prices still below USD20 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e), a significant gap remains to reach the estimated USD50–USD100/tCO2e required by 2030 to achieve meaningful decarbonization and meet the Paris Agreement targets. The report also emphasizes that marginal abatement costs, which reflect the cost of shifting from high to low-carbon technologies, are as high as USD800/tCO2e. The currently low carbon prices risk allowing emitters to simply pay for ETS permits or carbon taxes rather than invest in emission reduction.

Prioritizing fixed cap reduction rates and permit supply management

While details are still forthcoming, China’s planned adoption of absolute caps should be accompanied by a fixed reduction rate — similar to the EU ETS’s linear reduction factor (LRF) — to establish the pace at which emission allowances decrease annually. The rate of reduction should rise over time to effectively tighten supply, support prices, and enhance market certainty. The EU ETS’s LRF started at 1.74% in 2013 and is expected to increase to 4.4% from 2028. The only two Asian ETSs with absolute caps (South Korea and Kazakhstan) lack a strict, gradually increasing reduction rate. While this allows for cap adjustment flexibility in response to economic conditions, these modest and less predictable reductions limit the effectiveness of tightening supply. China should adopt a clear, progressively increasing cap reduction rate to enhance market certainty and strengthen price signals.

Another priority is to reduce the number of free permits and introduce auctions to allow the market to determine carbon prices. Currently, China allocates all ETS permits for free, a practice that not only shields incumbent emitters from the actual cost of emissions but also deprives the government of auction revenues that could be reinvested to fund climate and other social and economic initiatives. Contrastingly, more than 50% of the EU ETS permits are distributed through auctions.

The EU ETS also uses a Market Stability Reserve (MSR), which automatically adjusts the supply of permits for auctions based on predefined thresholds. When the number of allowances in circulation exceeds or falls below these levels, the MSR withdraws or releases allowances, thereby maintaining market stability and minimizing price volatility. South Korea’s system, by contrast, relies on government intervention to address excessive price fluctuations, such as adjusting allocations or trading rules. These discretionary measures are less predictable and often less effective in their impact. Similarly, China’s regional ETSs employ discretionary interventions that lack transparency. These aspects should also be taken into consideration when setting caps for China’s national ETS.

Protecting exports while retaining carbon revenues for domestic use

Another factor supporting the development of a functioning carbon market with prices high enough to drive decarbonization is the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will be implemented in 2026. The CBAM will impose carbon costs on imports from countries with weaker climate policies, as evidenced by lower carbon coverage and prices. This underscores the urgency for economies like China and other Asian countries to advance their carbon markets to a) maintain the competitiveness of their exports compared to countries with effective carbon pricing schemes, and b) ensure that the revenue leakage represented by CBAM taxes paid to the EU is replaced by revenue generation for domestic use. This is crucial as Asia accounted for EUR1.1 trillion, or 46%, of the EU’s total imports (excluding trade between EU member states) in 2024. China was the EU’s largest import partner that year, with imports totaling EUR519 billion.

It was previously estimated that in the first phase of CBAM, China’s steel and aluminum sectors would need to pay around RMB2 billion to RMB2.8 billion annually. This would add approximate costs of RMB652–690 per tonne for steel and RMB4,295–4,909 per tonne for aluminum. With the recent inclusion of these sectors in the national ETS, the actual impact is expected to be lower than these earlier assessments. However, with EU ETS permits trading at an average of approximately USD80/tCO2e in the first nine months of 2025 — compared with only about USD11/tCO2e for China’s carbon credits — domestic carbon prices will need to increase significantly to retain carbon revenues within the country.

Strengthening climate ambition and regional leadership

China accounted for 29% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2024. It aims to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. In its latest Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), China further pledged to reduce net GHG emissions by 7%–10% from peak levels and increase the share of non-fossil fuels in energy consumption to 30% by 2035. A well-designed carbon market can complement the country’s strategies and accelerate progress towards these goals.

While the changes in China’s ETS are largely consistent with international best practices, strong enforcement will be critical to ensure credibility and effectiveness. If implemented successfully, an important precedent can be set for other Asian markets. While several countries in the region have already established carbon markets or are preparing to introduce them, these systems have yet to drive significant decarbonization due to low prices and weak market design. Early flexibility measures aimed at easing participation and reflecting national circumstances have kept prices too low to facilitate emission reductions.

With significant untapped potential, governments should continue to refine market design, improve transparency, and strengthen enforcement to enhance credibility. This would improve the effectiveness of domestic systems and lay the foundation for stronger linkages and interoperability across markets. China has the opportunity to lead Asia by designing an ETS that is fully fit for purpose.