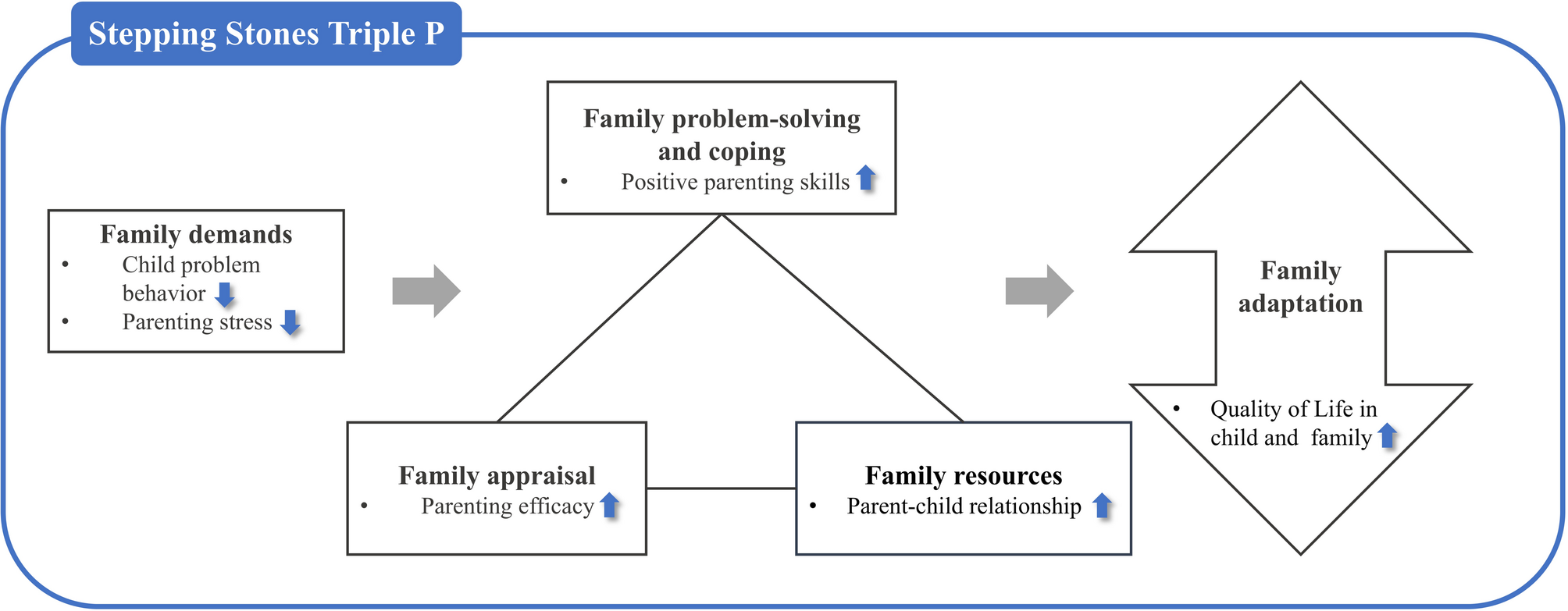

To our knowledge, our pilot study is the first attempt to conduct Level 4 Group SSTP among South Korean families. We adapted the Group SSTP to South Korean families of children with DDs and evaluated the intervention’s feasibility and effectiveness on the child and family outcomes based on the Resiliency Model [22].

Participants expressed high satisfaction with the intervention, indicating its potential in South Korea. They valued learning practical parenting skills and sharing insights with peers, with some expressing a desire to maintain connections after the sessions. While remote sessions eased participation for some, others preferred in-person meetings, suggesting that future research could offer both options. Overall, the feedback confirmed the intervention’s feasibility.

However, attrition was a potential consideration in assessing the feasibility, as two parents withdrew early. One, a single mother of a child with significant behavioral challenges, discontinued after the first session due to difficulty managing her child during the session, noting the absence of caregiving support. Another mother missed several sessions due to personal reasons, without attributing her non-participation to dissatisfaction with the intervention or difficulties with the virtual format.

Compared to traditional in-person delivery, the virtual format improved accessibility, enabling parents from distant regions to participate in real time. Nevertheless, the absence of a controlled physical environment may have introduced distractions that affected retention. The challenges experienced by the caregiver may have resulted from the combination of the specific characteristics of this intervention with its online delivery format, rather than the modality alone. For example, the parent might have more readily participated in an online program that actively engaged the child, thereby reducing the cognitive and logistical demands of attending to both the session and the child simultaneously. This highlights the need to assess not only the feasibility of the delivery modality in isolation but also the feasibility of the entire intervention package within its implementation context. Future research should explore strategies such as providing additional support for childcare or incorporating content that actively engages children.

In terms of individual-level score trends, Subject 6 demonstrated the most positive changes in all outcomes, except for the child’s problem behavior, across the time points (T0–T2). The baseline scores for the outcomes were relatively unfavorable, and the mother was young and had a lower economic status. She expressed a desire to participate in an additional round of the intervention, as she found it particularly helpful in learning parenting strategies tailored to her child. This participant did not report prior intervention experience, which may help explain the notable improvements observed. On the other hand, Subject 2 exhibited the least favorable outcomes, including declines in parenting efficacy, positive parenting skills, and family QoL. Notably, this participant’s baseline scores were relatively high, and her economic status was comparatively more favorable than that of other participants. The differences between the two subjects may stem from disparities in opportunities to participate in various interventions, influenced by their differing socioeconomic statuses. These patterns, though based on a small sample, highlight the importance of considering caregiver background and tailoring program outreach and delivery to reach underserved populations who may benefit most. Thus, future studies should investigate caregivers’ backgrounds, including prior intervention experiences with various delivery modalities such as virtual formats, to better understand how these may influence participation and engagement. Moreover, as in other countries where SSTP is implemented nationally [26], adopting the program at a national level in South Korea may be particularly beneficial for underserved families who lack access to parenting resources.

Additionally, although Subject 2 reported a high level of satisfaction with the intervention and provided positive qualitative feedback, she rated the usability and usefulness of the mobile app the lowest among all participants and expressed difficulties with app usage. Conversely, Subject 7, who reported the second-highest ratings for the usability and usefulness of the mobile app, demonstrated the greatest reduction in the child’s behavioral problems. This may suggest that the mobile app functioned as a supplementary tool in delivering the intervention, and its seamless integration into the intervention process could enhance overall effectiveness.

In terms of group level, we observed that comparisons between T0 and immediately post-intervention (T1) showed no statistically significant differences. However, we found significant effects of the intervention on child and family outcomes, including children’s behavior problems, QoL, parenting stress, efficacy, positive parenting behavior, and the parent-child relationship, from pre-intervention to one month post-intervention (T2).

One possible explanation for these findings is the cumulative effects of the intervention. SSTP focuses on providing families with practical parenting strategies that align with their values and needs, aiming to empower them to manage challenges independently [23]. Even after the intervention, families continued to apply positive parenting skills, which may have contributed to the improved outcomes observed over time.

The main limitation of our study was its small sample size. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution. The outcome data gathered only from participant reports may have had a self-report bias. Including other informants may provide a more balanced assessment of the intervention.