Key takeaways

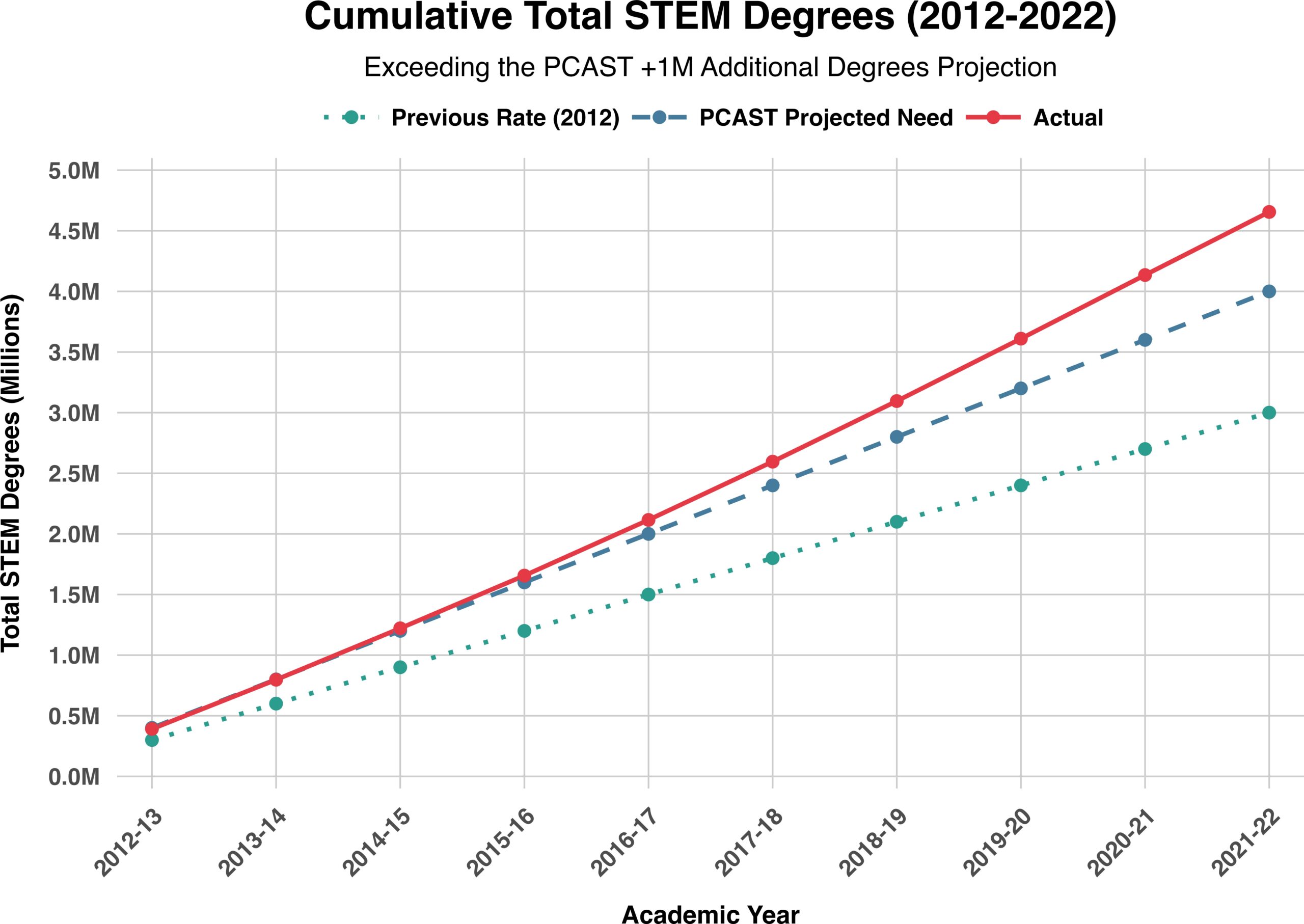

- Between 2012 and 2022, a national target of 4 million STEM degrees earned in the United States was surpassed by 16%, cumulatively totaling 4.65 STEM degrees over that decade. This exceeded a projected need of 4 million, which was one million more than the baseline projection.

- Degree-completion rates for STEM undergraduates have improved to now match or even exceed those of non-STEM peers in many cohorts.

- Representation of Hispanic students and women in STEM undergraduate programs has shown notable gains. But significant gaps remain for Black students and American Indian and Alaska Native students.

- The study emphasizes that keeping and improving national‐level data collection is critical for sustaining STEM education progress and policy oversight.

A recent analysis of national higher-education data by a researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, found that the United States exceeded the goal of producing one million more graduates in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) over the course of a decade. That goal, set in a 2012 report by then-President Barack Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), was one of several national objectives created to maintain America’s scientific leadership position in an increasingly competitive global landscape.

The analysis, by National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow Haider Ali Bhatti was, on the one hand, good news: It indicates that the expansion of programs intended to support STEM education outcomes in the years following the report’s publication yielded a successful return on investment.

But at the same time, Bhatti’s study serves as a warning about the danger of tearing down federal institutions and the information infrastructure they provide. His findings underscored the vital importance of keeping and improving national-level data collection for sustaining STEM education progress and establishing policies and priorities that aim to maintain U.S. leadership in an increasingly competitive scientific and economic landscape.

Let the data speak

The study is framed in the present-day context of the growing challenges faced by U.S. universities: public skepticism of their value, claims of ideological indoctrination, and the ongoing dismantling of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

“These criticisms demand higher education research to demonstrate tangible outcomes of progress informed by evidence-based evaluations,” said Bhatti, in UC Santa Cruz’s Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology. “In this climate of heightened public scrutiny, undergraduate STEM education offers a particularly valuable disciplinary domain to assess higher-education outcomes given its importance to national workforce development goals and global economic competitiveness.”

Relying largely on data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), Bhatti found that the number of STEM degrees obtained in the decade following the 2012 “Engage to Excel” report exceeded the goal of an additional million graduates by 16%. He also found that the proportion of STEM degrees among all degrees conferred increased over the decade, reversing previous declining trends.

Stemming economic threats

In addition, STEM employment expanded correspondingly, with growth surpassing the PCAST report’s projections, according to Bhatti. In his study, he explained how the 2012 report emerged as a response to specific workforce and educational concerns facing the country in the years prior. While America had historically relied on foreign-born STEM professionals to satisfy unmet workforce demands, the presidential advisory council warned that this strategy was no longer sustainable.

STEM education and employment opportunities were increasing globally, making other countries potentially more attractive to STEM-trained workers and creating potential vulnerabilities for American economic stability, the study states. Furthermore, other research showed that STEM-related jobs represented some of the best opportunities for upward mobility in the American economy, offering high wages and lower unemployment rates than other sectors.

The 2012 report concluded that expanding access to these high-quality careers provided a potential pathway to reduce income inequality if more Americans were trained in STEM fields. Against this backdrop of global competition and domestic opportunity, PCAST established concrete, measurable goals to address what the report characterized as a critical “decision point” for American educational and economic leadership at the time of its publication.

Other encouraging and stubborn trends

In his study, Bhatti cited other research that analyzed national data to assess progress on two other goals in the PCAST report: improving retention rates among students in STEM fields, and increasing demographic representation. At the time of the report, only 40% of students who started as STEM majors graduated with a STEM degree. To assess progress on that front, Bhatti presented results from research that analyzed longitudinal cohort data from the ongoing Beginning Postsecondary Students (BPS) study by NCES.

That research found improved retention rates among bachelor’s degree students in STEM fields, at 52%, along with a phenomenon that Bhatti said is more powerful: retention rates in STEM that were equal to or higher than those in non-STEM fields at the bachelor’s degree level. Given the typical amount of exploration and changing of majors that undergraduates do, Bhatti said it was encouraging to see comparatively less attrition in STEM disciplines than in other fields.

In regards to increasing demographic representation, Bhatti reported mixed progress, with national data showing substantial gains for Hispanic students and women, but also persistent gaps for Black and American Indian/Alaska Native students. According to NCES data, the share of Hispanic STEM degree recipients increased from 9.5% to 14.7%.

Bhatti also found that the percentage of science and engineering degrees earned by women rose from 43% to 49% at the associate’s level, while remaining stable at about 50% for bachelor’s degrees over the past decade.

But overall, NCES data show an upward trend for women in STEM: Between 2012 and 2022, the share of women who earned STEM degrees increased steadily from just under 32% (124,853) to over 37% (193,625).

Refuting critics with proof of ROI

Besides NCES, Bhatti examined other national reports, data sets, and longitudinal studies spanning over 10 years since the publication of the PCAST report. And now, more than a decade later, he said if higher education’s critics are correct, we would expect minimal to no progress toward these goals. But his study clearly showed otherwise.

“Overall, these results reveal patterns that challenge public narratives about the diminishing state of higher education—particularly in undergraduate STEM education,” Bhatti concluded. “These findings provide an evidence-based foundation for both evaluating past investments and guiding future strategies to strengthen America’s talent development in the evolving global STEM ecosystem.”

Bhatti emphasized that NCES is a division of the U.S. Department of Education, which has been critically defunded and affected by mass layoffs due to federal restructuring. “This work shows the importance of data infrastructure to check if we, as a nation, are on track in the increasingly competitive world of STEM,” he said. “We need things like NCES to enable evidence-based evaluations of our educational progress.”

While his study is largely positive about recent trends in undergraduate STEM education, Bhatti also noted several caveats. The decade covered by his study included large‐scale reforms as well as variability across institutions and regional systems. Thus, Bhatti said national averages may have masked pockets of underperformance.

In addition, while degree production and completion have improved, Bhatti’s findings stop short of documenting the quality of the learning experience, the alignment of degrees with workforce needs, or long‐term career outcomes. He points out that “degree counts alone are insufficient; we must also ask whether graduates are succeeding in the jobs of today and tomorrow.”

His analysis, “One million more: assessing a decade of progress in undergraduate STEM education,” originally appeared in the journal Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education on August 21.