Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The times call for a little tenderness. While armies rage and the climate goes berserk, Susumu Shingu offers a balm in the form of seemingly weightless sculptures that dance in the slightest breeze. The small exhibition Susumu Shingu: Elated! turns a white-walled gallery at the Japan Society in New York into an indoor oasis, where you can sense what Dylan Thomas called “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”. It’s a gentle but eloquent response to negativity.

Shingu has no time for doom. A wall text announces his credo: “I want to convey to the next generation the special charm of this unique planet called Earth. I’m going to do everything I can do for that, believing in the power of art.” If another artist made that statement, it might seem grandiose or naive, or both. But he backs up his aspirations with graceful humility and serious technical know-how. Working with industrial materials — stainless steel, carbon fibre and polyester — he constructs gizmos that express nature’s unseen essences, such as wind, gravity, momentum, and light.

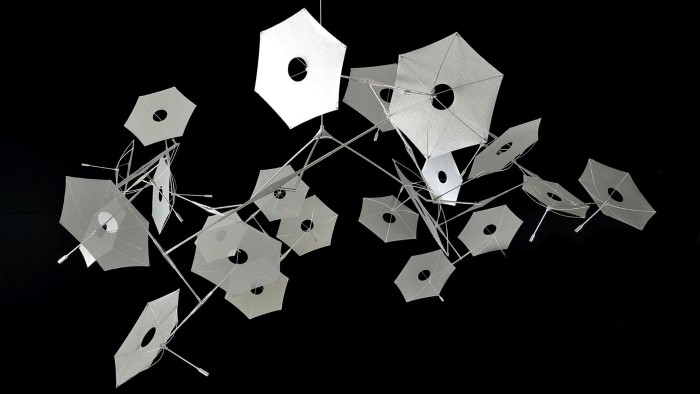

It’s disorienting to walk in from the agitated heat of Midtown to this serene bower, like going inside to get outdoors. Three suspended sculptures stir in slow-flowing currents produced by an electric fan. “Wings of Freedom” (2022) glides like an airborne creature — a magnified butterfly or a miniaturised pterosaur, say. The hexagonal sheets of “Little Cosmos” (2014) link the microscopic to the infinite. They could be galaxies or spores, weaving and flapping in a series of intricate dance steps. The work envelops you, casting a crowd of bobbing shadows on the walls and floor.

The movement is constant but never hectic. In “Diary of Clouds” (2016) yellow panels gyrate languorously, merging into complicated forms, then scattering in separate trajectories. Yet in its quiet way, it’s a piece about nature’s remorseless, impersonal violence. Shingu deconstructs the atmosphere, rendering wind as an alternately destructive and creative power. A zephyr’s caress and a killer tornado are manifestations of the same wondrous energy.

“My works are ways of translating the messages of nature into visible movements,” he has said. “What I try to show is the beauty of our planet and how lucky we are to be born here as human beings.”

He knows something about good fortune. Born in Osaka in 1937, he came of age during Japan’s postwar boom and studied oil painting at Tokyo University of the Arts, where he fell in love with Italian Renaissance painting. He evidently had the resources and the leeway to pursue that enthusiasm, because he learned Italian, moved to Rome (where he studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti), and focused his passion on the work of Piero della Francesca. Perhaps inspired by Piero’s affinity for geometrical forms, Shingu began to veer away from painting towards sculptural abstraction.

His luck held. In 1965, a job as a tour guide for Japanese visitors to Italy brought him into contact with the shipbuilding magnate Kageki Minami, who appointed himself his patron. It’s pleasing to imagine these two enterprising men from Osaka, communing over a bottle of wine and finding common ground between sculpture and marine engineering.

Minami urged his new friend to spend some time at his shipyard back home, where he could learn about aerodynamics from a corps of experts. Shingu took up the challenge, and it paid off. The kinetic work in his first solo exhibition earned him a prime spot in one of the major showcases of Japanese culture and technology: the 1970 World Expo in Osaka. He was a budding international star.

Minami stepped up his support, bankrolling a visit to the United States, where the resourceful and energetic young man published his first monograph and served as a visiting artist at Harvard. He obtained a pilot’s licence, which effectively allowed him to become one of his own kinetic sculptures, riding atmospheric currents in a lightweight, steel-frame apparatus. And he courted the designer Charles Eames, first with letters, then with a visit to his Los Angeles home, and later by internalising his aesthetic. At the Japan Society, you can see Eames’s impact in the primary-coloured whimsicality, especially in the parade of toy-sized maquettes that twist, toggle and pirouette behind glass.

Unavoidably, the show lacks Shingu’s biggest and best-known pieces, the public commissions that adorn universities, plazas and airports around the world. His ambitions have always been global, so even if you’ve never heard his name, you may have seen his work at Hermès in Tokyo, the New England Aquarium in Boston, or Olympic Park in Seoul. In 2000 he sent “Wind Caravan,” an ensemble of 21 pieces, on a tour of Indigenous communities in New Zealand, Finland, Morocco, Mongolia, and Brazil.

At the Japan Society, that panoramic breadth gets distilled into a more intimate experience. Drawings, three-dimensional models and children’s books speak to how dexterously he skips between the vast and the tiny. Shingu often throws off the viewer’s sense of scale, as if we were observing through a telescope without knowing from which end. The largest in a trio of freestanding sculptures anchored to a podium is the seven-foot-high “Moon Boat” (2022), a pair of wind-filled vessels that pitch, roll and yaw in mid-air — essentially miniature spaceships.

The humblest objects are also the most charming: pop-up books for kids, filled with semi-abstracted natural wonders. A pod of blue whales breaches the surface of a violet ocean, camels strut across orange sands, purple birds shoot across an empty sky. Don’t be fooled by the guilelessness, though; Shingu has spent a lifetime working to preserve his childlike wonder and merge it with technical sophistication and a focused sense of awe.

To August 10, japansociety.org