Nectocaridids are enigmatic Paleozoic animals with a controversial position. These creatures were adapted for swimming, having fins, a head region with stalked camera eyes, and paired tentacles. Previous hypotheses have placed them in their own crustacean-like phylum, chordates, cephalopods, or radiodonts. An analysis of new fossils from North Greenland shows nectocaridids are actually early descendants of arrow worms, also known as chaetognaths. This discovery means the rather simple marine arrow worms had ancestors with much more complex anatomies and a predatory role higher up in the food chain.

Life reconstruction of Nektognathus evasmithae. Image credit: Bob Nicholls.

“Around 15 years ago a research paper, based on fossils from the famous Burgess Shale, claimed nectocaridids were cephalopods,” said University of Bristol paleontologist Jakob Vinther.

“It never really made sense to me, as the hypothesis would upend everything we otherwise know about cephalopods and their anatomy didn’t closely match cephalopods when you looked carefully.”

In new research, Dr. Vinther and colleagues described Nektognathus evasmithae, a new nectocaridid species from the 519-million-year-old Sirius Passet Lagerstätte of North Greenland.

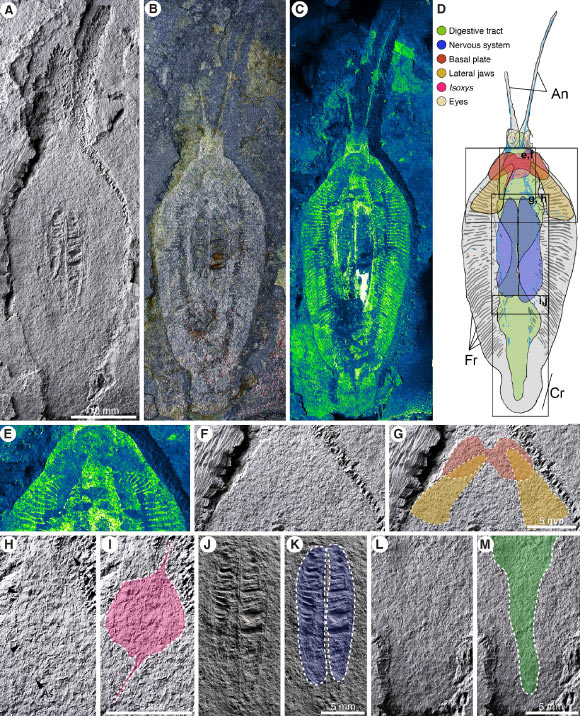

By analyzing 25 fossil specimens of Nektognathus evasmithae, they were able to pinpoint where nectocaridids fit into the tree of life.

“We discovered our nectocaridids preserve parts of their nervous system as paired mineralized structures, and that was a giveaway as to where these animals sit in the tree of life,” Dr. Vinther said.

Nektognathus evasmithae, holotype. Image credit: Vinther et al., doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adu6990.

Recently, the paleontologists uncovered fossils in Sirius Passet belonging to another branch of the animal tree — a small group of swimming worms called arrow worms or chaetognaths.

“These fossils all preserve a unique feature, distinct for arrow worms, called the ventral ganglion,” said Dr. Tae-Yoon Park, a paleontologist at the Korean Polar Institute.

The ventral ganglion is a large mass of nerves situated on the belly of living arrow worms, which is unique to this type of creature.

The unique anatomy of the organ combined with the special preservation conditions means it sometimes is replaced by phosphate minerals during decay.

“We now had a smoking gun to resolve the nectocaridid controversy,” Dr. Park said.

“Nectocaridids share a number of features with some of the other fossils that also belong to the arrow worm stem lineage.”

“Many of these features are superficially squid-like and reflect simple adaptations to an active swimming mode of life in invertebrates, just like whales and ancient marine reptiles end up looking like fish when they evolve such a mode of life.”

“Nectocaridids have complex camera eyes just like ours,” Dr. Vinther said.

“Living arrow worms can hardly form an image beyond working out roughly where the Sun shines.”

“So, the ancestors of arrow worms were really complex predators, just like the squids that only evolved about 400 million years later.”

“We can therefore show how arrow worms used to occupy a role much higher in the food chain.”

“Our fossils can be much bigger than a typical living arrow worm and combined with their swimming apparatus, eyes and long antennae, they must have been formidable and stealthy predators.”

“As further evidence for nectocaridids being swimming carnivores, we found several specimens with the carapaces of a swimming arthropod, called Isoxys, inside their digestive tract.”

The study was published this week in the journal Science Advances.

_____

Jakob Vinther et al. 2025. A fossilized ventral ganglion reveals a chaetognath affinity for Cambrian nectocaridids. Science Advances 11 (30); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adu6990