This study translated and culturally adapted the SARC-F into Persian and evaluated its psychometric properties for older adults attending outpatient geriatric clinics. The results indicate that the Persian adoption of the SARC-F is both reliable and valid for possible sarcopenia screening.

The translation and pre-testing process to achieve a culturally adapted version was similar to the methods used for various other translations, including the German version [14]. The values of CVI and CVR indicated that the questionnaire had appropriate content validity and none of the items required modification. Trivedi et al. also reported similar results for the Gujarati version of the SARC-F [25].

The translated SARC-F demonstrated satisfactory reliability. Specifically, the test-retest reliability was excellent, closely aligning with the Greek version (ICC = 0.93) [26]. The internal consistency was also acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79, similar to the original version reported by Malmstrom et al., with values ranging from 0.76 to 0.81 [12]. Overall, various versions of this tool have shown good reliability [27].

The Persian SARC-F showed strong negative correlations with handgrip strength (HGS) and gait speed, which are criteria for possible sarcopenia, thereby confirming concurrent validity. It also showed a significant positive correlation with age (ρ = 0.257) and a significant negative correlation with LEIPAD scores (ρ = −0.646). Similarly, Parra-Rodriguez et al. reported significant correlations between SARC-F scores and handgrip strength, gait speed, quality of life, and age [9]. This result is consistent with findings from other studies [26, 28]. Contrary to expectations, no significant correlation was found between SARC-F scores and calf circumference (CC). CC is acknowledged as an indicator of muscle mass in older adults. It serves as a proxy for measuring muscle mass [19]. While the SARC-F questionnaire is a suitable screening tool for detecting impaired physical performance, it may not directly reflect muscle mass. This is consistent with the findings of Drey et al., who also reported a lack of association between SARC-F scores and muscle mass [14]. CC is not a reliable indicator of the functional aspects of sarcopenia. Additionally, several factors can affect the accuracy of CC measurements. For example, calf edema can exaggerate the muscle volume, thereby compromising the precision of CC as a screening tool for sarcopenia [29]. Another possible reason can be the presence of sarcopenic obesity (SO), which is defined as the simultaneous presence of obesity and sarcopenia [30].

The study’s findings underscore the significant differences in various variables between individuals with SARC-F scores of ≥ 4 and < 4. These differences in age, gender, education level, number of medications, polypharmacy, gait speed, handgrip strength, and height can highlight the multifaceted nature of sarcopenia.

The investigation of construct validity confirmed convergent validity with the strong correlation between the physical functioning and self-care domains of the LEIPAD questionnaire and the Persian SARC-F and established divergent validity with the weaker correlations between the Persian SARC-F and other domains such as depression and anxiety, cognitive functioning, and social functioning. While the Persian SARC-F’s strong correlations with the physical functioning and self-care domains support the construct validity, it’s important to note that these domains do not directly measure sarcopenia. They are relevant to the functional impairments commonly associated with sarcopenia. The self-care domain measures older adults’ capacity to do daily activities independently [31]. Meanwhile, the SARC-F questionnaire is a suitable screening tool for identifying individuals with impaired physical performance [14]. Both physical performance and muscle strength can predict decreases in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Older adults who are dependent on ADLs and IADLs are also more likely to have poor muscle measures defined as low muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance, which further limit their ability to perform activities [32]. Gasparik et al. reported similar findings, confirming the convergent validity of the SARC-F questionnaire through significant correlations with similar domains of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire and Sarcopenia quality-of-life (SarQoL) questionnaire. Additionally, they demonstrated divergent validity, evidenced by weaker correlations between SARC-F scores and the domains of the SF-36 and SarQoL questionnaires that differ from the SARC-F [33].

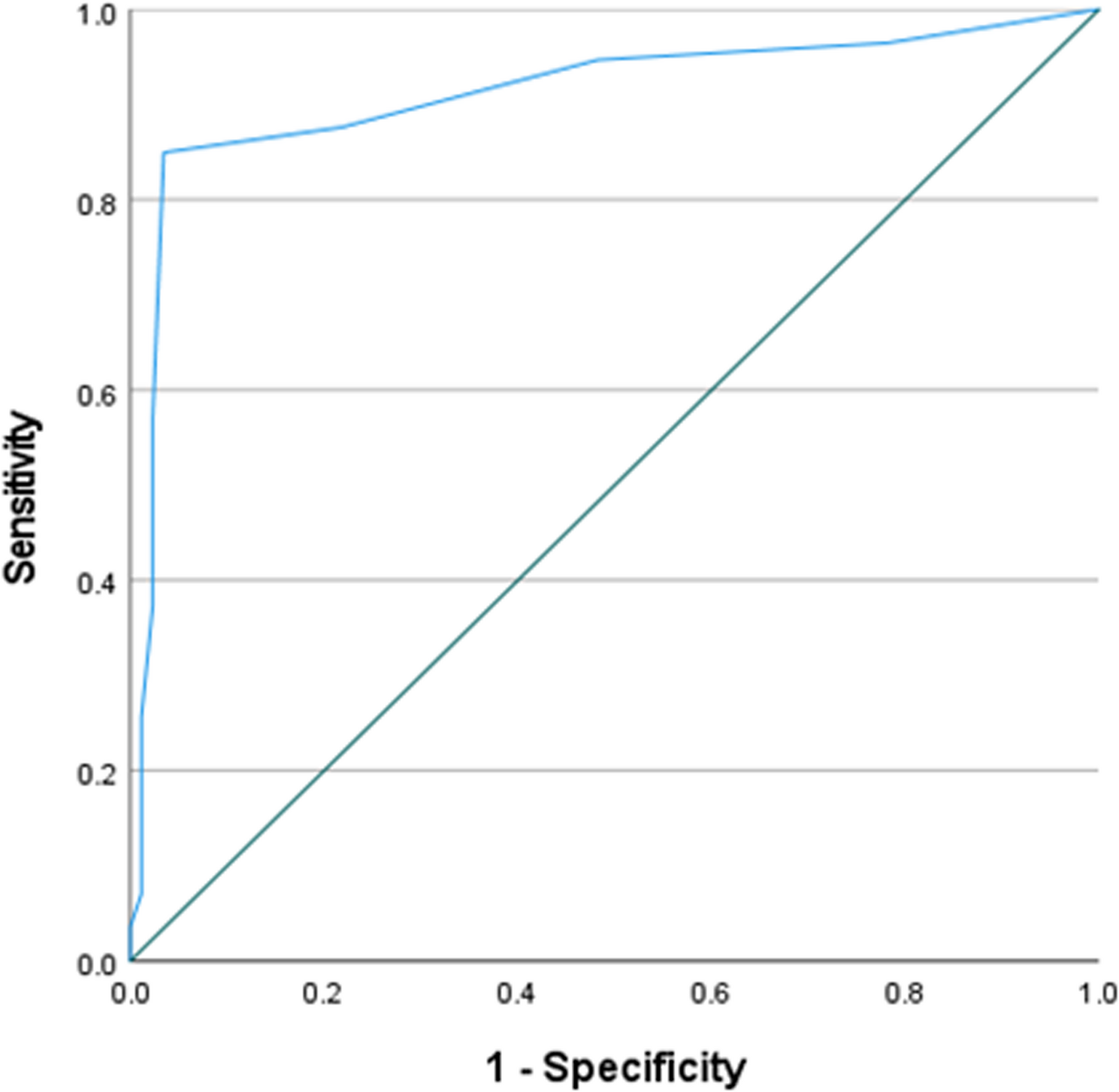

In numerous studies, the SARC-F questionnaire has demonstrated low to medium sensitivity, medium to high specificity, low positive predictive value, and high negative predictive value [27]. However, in the present study, all these measures were high. This could be due to the use of AWGS 2019-possible sarcopenia diagnostic criteria in the present study. In addition to the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, the AWGS and EWGSOP2 have outlined criteria for’possible sarcopenia,’as defined by the AWGS, and’probable sarcopenia,’as outlined by the EWGSOP2. These criteria exclude the assessment of muscle mass, instead focusing on muscle strength. Additionally, the AWGS recommends the assessment of physical performance. In most studies, these criteria have not been used to determine diagnostic characteristics. The SARC-F has the capability to identify impaired physical function [14]. Its items just focus on muscle strength and performance; they do not assess muscular mass (MM) [34]. Therefore, using possible/probable sarcopenia diagnostic criteria seems more reasonable. In the study by Drey et al., the German SARC-F demonstrated higher sensitivity, specificity, and PPV with EWGSOP2 probable sarcopenia criteria compared to EWGSOP2 sarcopenia criteria [14]. Similarly, Gasparik et al. reported the same results for the Romanian version of SARC-F [33]. The high sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV observed in this study highlight the Persian SARC-F’s robust performance in both identifying and ruling out possible sarcopenia. For a definitive diagnosis of sarcopenia, additional tests are necessary.

The SARC-F questionnaire has been reported as inadequate for elderly individuals requiring nursing care, particularly those with complex health conditions or cognitive impairments such as dementia or aphasia [35]. However, in this study, the Persian SARC-F exhibited high specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values. Several factors likely contributed to these findings. First, the study sample consisted of community-dwelling older adults attending geriatric clinics as outpatients. Participants with severe health conditions—including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, musculoskeletal injuries, or other impairments that could interfere with physical assessments (e.g., grip strength, walking speed, height, and weight measurement)—were excluded. As a result, the study population differed significantly from elderly individuals residing in nursing care facilities. Second, as previously noted, the possible sarcopenia criteria were employed to assess the validity and predictive power of the SARC-F. Unlike definitive sarcopenia criteria, the possible sarcopenia definition does not necessitate muscle mass measurement [7]. Given that the SARC-F evaluates muscle strength and performance [34]. Its predictive power is inherently higher when applied within the framework of possible sarcopenia rather than definitive sarcopenia. Similar findings have been reported in studies examining different language versions of the SARC-F. For instance, in the German version [14], sensitivity increased by 12%, specificity by 20%, and PPV by 60% when the possible sarcopenia criteria were applied instead of definitive sarcopenia criteria. Likewise, in the Romanian version [33], sensitivity, specificity, and PPV increased by 4%, 16%, and 38%, respectively, under the same conditions. These results further support the effectiveness of the SARC-F when utilized within the framework of possible sarcopenia criteria.

In this study, we conducted the first cross-cultural translation of the SARC-F questionnaire into Persian and evaluated its psychometric properties among Persian-speaking older adults. This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, socioeconomic factors—including income levels and social support—were not assessed, despite their potential influence on functional outcomes. Second, the study population was recruited exclusively from a limited number of outpatient geriatric clinics within a single urban setting, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to older adults in other regions, particularly rural communities. Additionally, the demographic characteristics of the sample may not comprehensively represent all socioeconomic or cultural subgroups within Iran, and variations in living conditions could impact the tool’s applicability across diverse populations. Furthermore, cultural differences—such as caregiving traditions, healthcare-seeking behaviors, and societal attitudes toward aging—may influence the relevance of the study’s findings in other Persian-speaking regions. Financial constraints prevented the inclusion of direct muscle mass measurements, which could affect the estimated sensitivity and specificity of the Persian SARC-F. If muscle mass data had been available, the study could have applied the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) diagnostic criteria to assess sarcopenia more rigorously. Moreover, because this was not a longitudinal or interventional study, it cannot show changes over time or responsiveness of the Persian SARC-F to interventions aimed at improving sarcopenia. Finally, the reliance on self-reported components in the SARC-F introduces a potential source of bias, as participants’perceptions and memory—particularly in reporting falls—may be affected by recall inaccuracies. Although efforts were made to exclude individuals with acute cognitive impairments, some degree of recall bias may persist.

Finally, we recommend further investigation into the psychometric properties of the Persian SARC-F in hospitalized older adults and nursing home residents, as well as an assessment of its responsiveness in interventional and longitudinal studies. Additionally, we suggest utilizing definitive sarcopenia diagnostic criteria to refine the calculation of the Persian SARC-F’s diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusion

The SARC-F questionnaire was systematically translated and cross-culturally adapted into Persian following established methodological guidelines to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence. Subsequently, its psychometric properties were rigorously evaluated in a sample of older adults attending outpatient geriatric clinics. The Persian version demonstrated strong validity and reliability metrics, as well as high diagnostic accuracy in both identifying individuals at risk for sarcopenia and effectively ruling out those without the condition. These robust findings underscore the utility of the Persian SARC-F as a practical and efficient screening tool for sarcopenia among community-dwelling older adults in Iran. By facilitating early identification, the use of this validated questionnaire has the potential to promote timely clinical interventions, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately improve health outcomes and quality of life for the aging population.