Recent conflicts in Europe and the Middle East have reignited fears about the use of nuclear weapons. What would a nuclear conflict do to the planet’s environment today?

In a new congressionally mandated report, oceanographer Nicole Lovenduski, who directs CU Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), outlined the dangerous fallout a nuclear war could bring, from firestorms and global cooling to ecosystem collapse and potentially irreversible ocean disruption.

Nicole Lovenduski/CU Boulder

“The ocean makes up three-quarters of our planet’s surface,” said Lovenduski, a professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. “Knowing how the ocean responds to changes in the environment is really important, because it can influence the global climate system.”

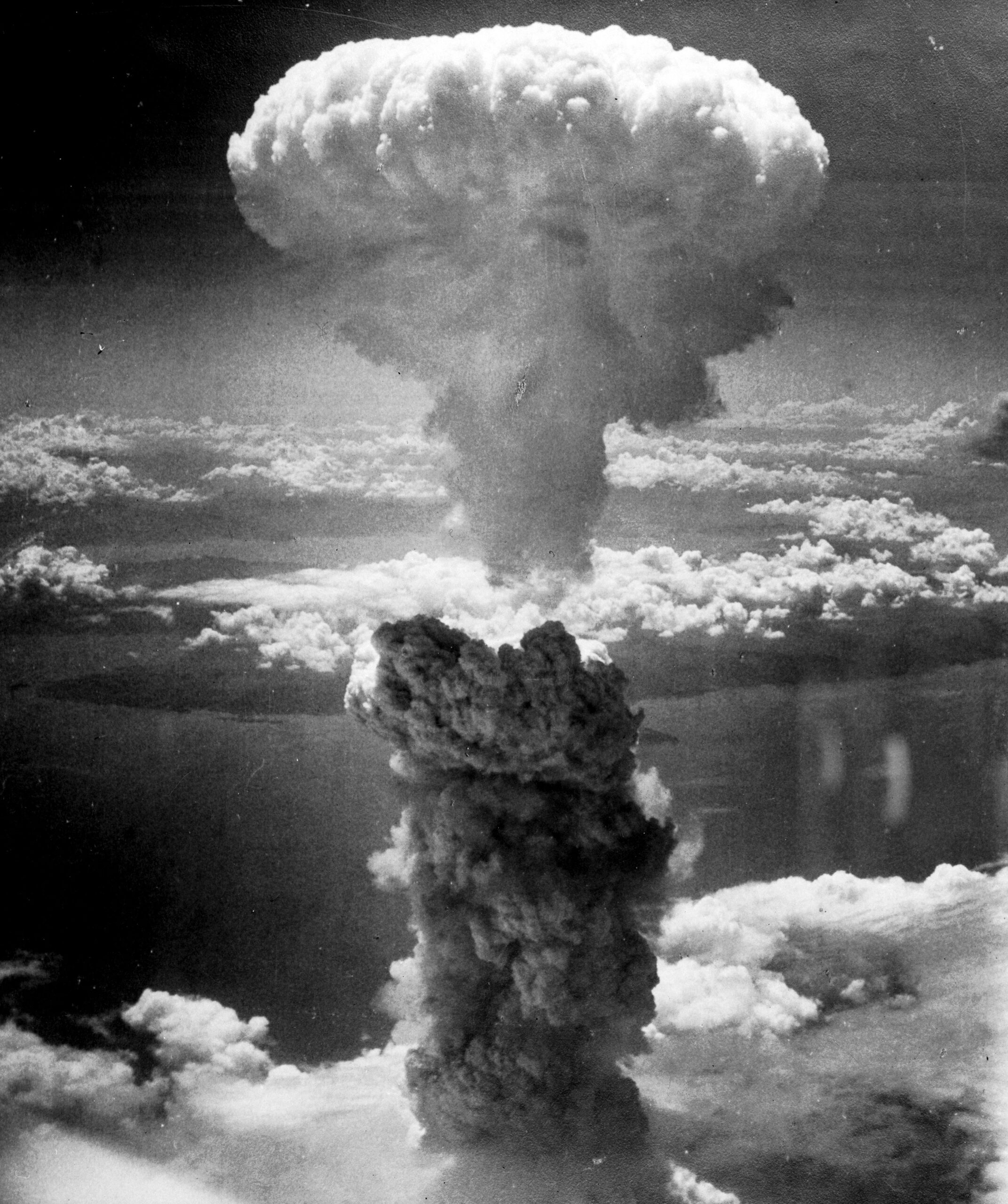

To date, the only use of nuclear weapons in conflict occurred in 1945, when the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. At the time, scientists were not tracking the environmental impact.

According to Lovenduski’s previous research, nine nations possess more than 13,000 nuclear weapons in the world, with the United States and Russia controlling the most operational nuclear weapons. The stockpiles in countries including India, Pakistan, China, and North Korea have also increased in the past eight decades.

Compiled by dozens of scientists across the country, the report aims to reevaluate the long-term environmental impacts of nuclear war using the latest scientific evidence.

“What we learned in writing the report was that we need additional scientific research to adequately describe the potential environmental and climate consequences of a nuclear conflict. But we know enough to know that a nuclear war would be a horrific outcome for humanity,” Lovenduski said.

CU Boulder Today sat down with Lovenduski to discuss how a nuclear conflict could change the ocean and why those changes are important.

What happens when a nuclear weapon is detonated?

Hypothetically, if there were to be a large-scale nuclear conflict on this planet that starts a lot of fire, there could be a firestorm that releases a lot of soot into the atmosphere. If it makes it all the way up into the stratosphere, where the air flow tends to be more stable, soot can stay there for a really long time and encapsulate the entire planet. That will lead to a dramatic reduction in the amount of sunlight that comes into our planet.

Without sunlight, we cannot have photosynthesis. Photosynthetic organisms, like plants on land and algae in the ocean, form the base of the food web for everything else. Without photosynthesis, we cannot have a source of food.

What would happen to the ocean, specifically?

If a lot of soot gets up into the stratosphere and blocks sunlight, it would cool the planet suddenly and significantly. That’s where the concept of nuclear winter first arose many decades ago.

Sea ice could extend all the way down to places in the Pacific and Atlantic that don’t currently have ice. That would affect how ocean currents move and whether surface seawater can sink and slow down large-scale circulation.

We may no longer have, for example, the Gulf Stream, bringing warm water northwards into the Atlantic, resulting in dramatic cooling of Northern Europe. Ocean currents are important in making sure many parts of the world are habitable for many.

Would people living far from coastal zones be impacted?

As a result of nuclear winter, crops on land could fail. We might look to the ocean for a source of food. But if the fish don’t have anything to eat, we’re all going to starve. So even if there’s a conflict, and it doesn’t affect us directly where we live, the global population is at risk of starvation.

How long would it take for the ocean to recover?

The atmosphere moves pretty fast. If the soot above the Middle East enters the stratosphere, it can spread globally within one to two years.

But the ocean moves really slowly. When water sinks in the North Atlantic, it can take hundreds, if not thousands, of years for that water to reemerge. So if you perturb the ocean, it can take a long time to recover. In some of the computer simulations we did, the simulation stopped before we even saw that recovery happen, because we were out of computing time. So we never saw the ocean recover in our simulations, which is scary.

I hope we don’t ever go down this road. I hope that the people in charge of deciding whether or not to engage in nuclear conflict can learn from some of the work that we have done. I hope that the report leads to a world where there is no nuclear conflict.