With mass deportations of migrants across America – not to mention reports of people being put in shackles or made to kneel and eat “like dogs” – Nora Guthrie is disappointed there hasn’t been more noise from musicians about the issue.

“I’ve been out protesting every weekend,” says the 75-year-old daughter of singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, and founder of the Woody Guthrie Archive. “And I’ve found myself asking, ‘Where are the songs for us to sing about this?’”

In need of a track that meets the moment, she turned to Deportee, a song her father wrote in 1948 in response to a plane crash in California that killed four Americans and 28 Mexican migrant workers, who were being deported. “A few days later, only the Americans were named and the rest were called ‘deportees’,” explains Nora’s daughter Anna Canoni, who recently succeeded her mother as president of Woody Guthrie Publications, over a joint video call from New York. “Woody read about it in the New York Times and the same day penned the lyric.”

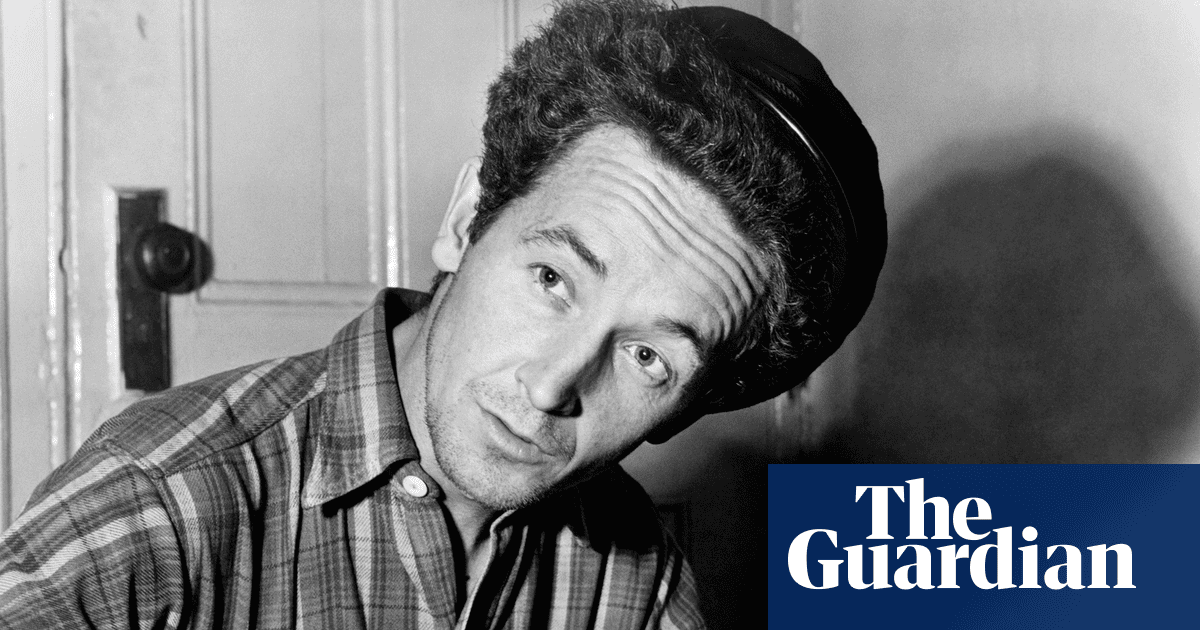

Originally a poem, the song (often subtitled Plane Wreck at Los Gatos) was first popularised by folk singers Martin Hoffman and Pete Seeger and has since been covered by the likes of Bruce Springsteen and Joni Mitchell. Now, though, leaps in AI audio restoration technology mean we can finally hear Guthrie’s own long-lost, home-recorded version, and it’s striking how powerfully it speaks to the way migrant workers are demonised today. They “fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil”, he sings, “and be called by no name except ‘deportees’”. Singer Billy Bragg argues that “When the ICE [US Immigration and Customs Enforcement] are rounding people up in fields, the song could hardly be more relevant.”

Initially a single, Deportee also appears on Woody at Home, Vol 1 and 2, a new 22-track treasure trove of Guthrie’s final recordings (including 13 previously unheard songs), made at home in 1951 and 1952, just months before he was first hospitalised with the neurodegenerative Huntingdon’s disease that led to his death aged 55 in 1967.

“He’d been blacklisted [during the McCarthy era, for activism], so he couldn’t perform as much and couldn’t get on the radio,” says Nora. “Huntingdon’s was seeping into his body and his mind. The tapes are a last push to get the songs out, because he senses something is wrong.”

Guthrie’s advocacy for migrant workers and social justice was informed by lived experience. Born into a middle-class family in Okemah, Oklahoma, he was just 14 when the family lost their home and he subsequently lived through the dust bowl, the Great Depression, the second world war and the rise of fascism. “He had to migrate from Oklahoma to California,” says Bragg. “He knew what it was like to lose your home, to be dispossessed, to go on the road. The Okies were really no different to those Mexican workers and were just as reviled.”

Performing with the slogan “This machine kills fascists” written on his guitar, Guthrie packed his seminal 1940 debut Dust Bowl Ballads with what Anna calls “hard-hitting songs for hard-hit people”.

He penned his most famous anthem, This Land Is Your Land – a new version of which opens Woody At Home with extra verses – after a road trip, as the lyric says, “from California to the New York island”.

“Woody wrote it because he was really pissed off with hearing Irving Berlin’s God Bless America on every jukebox,” says Bragg. “It annoyed the shit out of him. I’ve actually seen the original manuscript for the song and crossed out at the top is Woody’s original title, God Blessed America for You and Me, which I think gives him claim to be an alternative songwriter, the archetypal punk rocker.”

Between the early 1930s and the 1950s, Guthrie penned an astonishing 3,000 songs, recording more than 700 of them. The Woody at Home recordings were made at his family’s rented apartment in Beach Haven, Brooklyn, on a primitive machine given to him by his publisher with a view to selling the songs to other artists. With his wife out working, the increasingly poorly singer somehow managed to record 32 reels of tape while minding three kids. Sounds of knocks on doors, and even Nora as a toddler, appear on the tapes along with conversational messages.

“He’d write on the couch with the kids jumping on his head,” Anna says. “He’d write on gift wrappers or paper towels. We’ve found some of Woody’s most beautiful quotes in correspondence, like in a 1948 letter to [folk music champion] Alan Lomax, ‘A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it.’ Sometimes he only had time for a title. Everything was coming out so quickly he had to get it down.”

Woody at Home contains previously unheard songs about racism (Buoy Bells From Trenton), fascism (I’m a Child Ta Fight) and corruption (Innocent Man) but also showcases the breadth of Guthrie’s canon. There are songs about love, Jesus Christ, atoms … even Albert Einstein, whom he once met and took a train with. It tickles Nora that her father wrote “no less than five songs about washing dishes”.

Guthrie wrote Old Man Trump, also known as Beach Haven Race Hate, about their landlord, Fred Trump – father of Donald – and his segregative housing policies. Woody at Home premieres another song about him, Backdoor Bum and the Big Landlord. “It’s really the story of how the guy who has everything gives nothing and the guy who has nothing gives everything,” says Nora. “My favourite bit is when the landlord gets to heaven laden with gold. They send him to hell and he goes, ‘Let me see your manager. I’m gonna buy this place and kick you out.’ The arrogance and entitlement are astonishing, but it clearly defines someone we all know. We lived in Trump buildings. We know who they are.”

The family moved to Queens where, when Nora was 11, she answered the door to an inquisitive 19-year-old singer-songwriter called Robert Zimmerman. The future Bob Dylan had read Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory. “I was a little upset because I was watching American Bandstand and had to answer the door,” she chuckles. “There was this guy standing there who looked dusty and weird. I slammed the door and ran back to American Bandstand. But he kept on knocking.”

The 2024 Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown dramatises the iconic 1961 meetings between the teenage future legend and his hospitalised, dying idol. Nora loves the film, but points out: “My father wasn’t in a room on his own like in the movie. Woody was on a ward with 40 patients, in a psychiatric hospital because there were no wards for people with Huntingdon’s at the time. There was a sunroom to the side where Bob would meet him, take him pens and cigarettes. My memory is that Bob would not only sing his songs for Woody” – Dylan subsequently recorded a heartfelt tribute, Song to Woody – “but that he’d also sing my father’s own songs to him. I can’t emphasise enough how kind Bob was, but he understood that Woody needed to hear what he’d achieved.”

By then, Guthrie was very ill. “Because of Huntingdon’s I didn’t have a dad in the traditional sense people talk about,” Nora says with a sigh. “He couldn’t really talk or have long conversations like we’re having now. We couldn’t have physical contact because with Huntingdon’s your body’s always moving. You’d have to hold his arms back so you could hug him. If we ever went out to a restaurant people would look at us like he was drunk and that hurt.” Nora became Woody’s carer and, in her tireless curation of his legacy, has been caring for her father ever since.

“That happened accidentally,” she says, explaining how she’d spent 10 years as a professional dancer when – in 1991 – Guthrie’s retiring manager called her in to sort through boxes of his stuff. “One of the first things I pulled out was a letter from John Lennon,” she says, fetching the framed letter, sent to the family in 1975, for me to see. It reads: “Woody lives and I’m glad.” The next find was the original lyrics for This Land Is Your Land. “It was a treasure trove.”

From which there is more to come. His descendants hope to spark today’s young songwriters – and protesters – in the way Guthrie did for Dylan, Springsteen and countless others. “I see us as the coal holders,” says Anna. “We keep Woody’s ember burning so that whenever someone wants to ignite the fire in them, Woody is hot and ready.”