The late DJ Mehdi had a talent for bridging divides. At the height of the musician’s fame, Mehdi’s cousin Myriam Essadi recalls in a new documentary, he had to jet straight from a nightclub in Ibiza to his grandfather’s funeral in Tunisia. “He was wearing red glasses, white jeans and a jacket with a cross. In Tunisia! For our grandfather’s funeral!” Essadi laughs. “We didn’t get it. And in Tunisia you don’t mess with religion.”

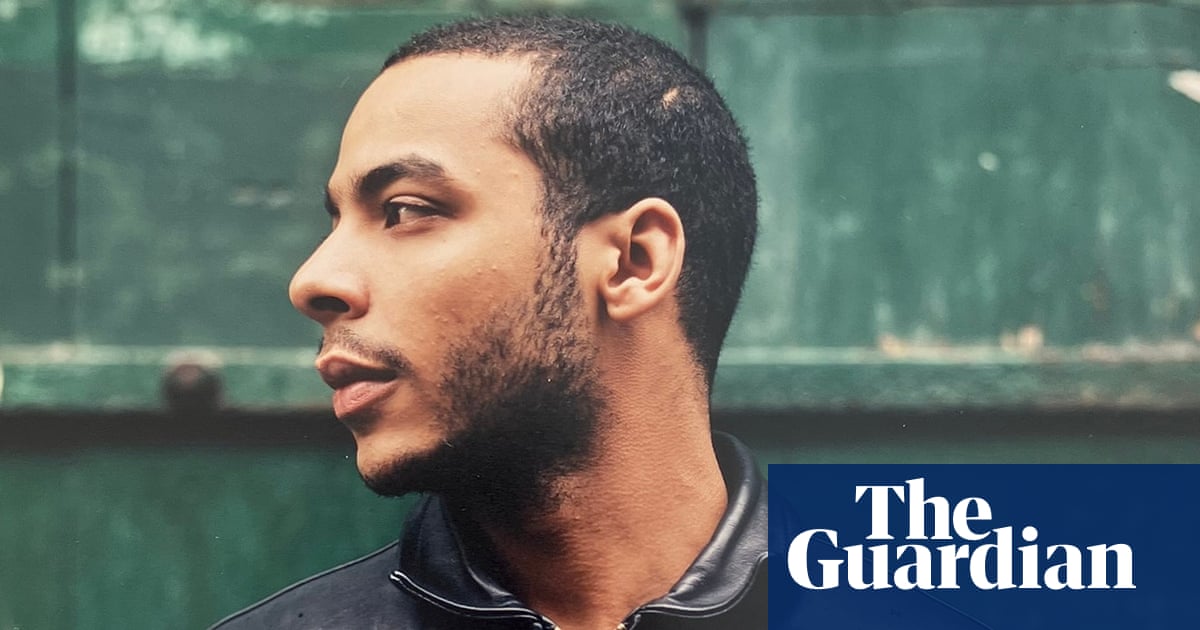

DJ Mehdi: Made in France, a six-part documentary now available with English subtitles on Franco-German broadcaster Arte, revisits the life and tragic death of one of the most fascinating, influential and misunderstood French musicians of his generation.

International audiences largely know Mehdi, who died in 2011 at the age of 34, for his work with Parisian label Ed Banger in the 2000s, spearheading a new wave of French dance music alongside artists such as Justice – they of the cross logo on Mehdi’s jacket – and SebastiAn. In France, however, his legacy is more complicated, opening up questions about the rift between hip-hop and dance music, as well as underlying divisions in French society.

Born to a French-Tunisian family in the north-west suburbs of Paris in 1977, Mehdi Favéris-Essadi rose to prominence for his production work with rap group Ideal J and hip-hop collective Mafia K-1 Fry. His first big hits came with 113, a rap trio whose 1999 album Les Princes de la Ville is considered one of the most important albums of the decade in France.

When Les Princes was released, dance music had already entered Mehdi’s life via Cassius duo Philippe Zdar and Boombass, whom he worked with on MC Solaar’s 1997 album Paradisiaque. Several of the leading producers of French house music had roots in hip-hop, including Pépé Bradock and Cassius themselves. But none were as well known within the rap world as Mehdi, and his pivot was not always warmly received. “You couldn’t switch from rap to electro or vice versa. In the other world, you weren’t legitimate,” Essadi explains in the documentary.

In the US, hip-hop and dance music were initially closely linked, sharing roots in soul and funk music as well as production methods, a connection Mehdi appreciated when he heard Daft Punk’s 1997 album Homework. “I thought: ‘That’s funny, we use the same machines, the same samplers, they live just around the corner, they’re about my age, that could have been me,’” Mehdi says in an archival clip.

By the late 90s hip-hop had risen to such prominence in the US that its leading artists tended to view dance music as a forgotten fad, if they thought about it at all. In the UK the opposite was true, with strength of British dance music eclipsing domestic hip-hop.

In France, homegrown rap was extremely strong in the late 1990s. In the media, however, it was often vilified, while dance music was viewed as the next big thing, thanks to the rise of acts like Daft Punk, Étienne de Crécy and Cassius. The tension between two types of music and their various associations – Parisian elite v working class, city v suburbs – was palpable.

“In 1997, if 47 guys and girls from [Paris suburb] Bobigny wanted to get into the Queen club [a Paris club known for house music] they couldn’t,” Boombass says in the documentary.

“To them we were just guys who smoked weed, only good for a bank robbery or to deal drugs to them,” Essadi adds. “‘You’re from the suburbs.’ That meant many different things to people from central Paris who went to the Palace club or to Bains Douche to listen to dance music.”

When Mehdi tried to bridge this gap – for example, with the Kraftwerk-sampling beat for 113’s Ouais Gros – the response was often negative. “When people heard it they thought: ‘Who are these guys hardcore rapping to music like this? I don’t get it,’” 113’s AP says in the documentary.

“I remember people stopping me in the streets, people from the rap world saying: ‘What’s Mehdi doing? Talk to him! What’s this new music, this crazy music,’” Essadi recounts.

Mehdi would go on to have huge success in electronic music off the back of the release of Signatune in 2007. “Signatune was soon being played by the most well-known DJs all across the globe and promoters all wanted to book DJ Mehdi for their events,” former Daft Punk manager Pedro Winter explains in Made in France.

The final part of the documentary shows footage of Mehdi’s international success, DJing at huge clubs and festivals alongside the Ed Banger crew to adoring, hedonistic crowds. It comes in sharp contrast to scenes of poverty and crime, burnt cars and drab suburban tower blocks, that mark the documentary’s first two episodes, examining Mehdi’s roots in hip-hop and the unfashionable outskirts of Paris.

Mehdi died on 13 September 2011 at the height of his international fame, when the skylight on the roof of his Paris home collapsed as he was celebrating the birthday of British producer Riton. “Four of them were sat on this … glass, sort of, roof,” Riton says in the documentary. “They just got to stand up, that’s when it like … made the roof collapse through. Then the next thing, we were just looking through this hole at this horrific scene.”

Tributes to Mehdi came in from the elite of the global dance music world, including US dubstep artist Skrillex and Ed Simons from the Chemical Brothers. And yet, for people in France in particular, this was only half the story.

“Internationally [Mehdi’s] probably best known as one of the frontrunners of the Ed Banger crew that defined an entire era,” Canadian DJ A-trak says at the end of the documentary. “But, of course, he has a huge legacy as the king of French hip-hop production and even just someone who brought together these unlikely pairings of scenes.”

“He helped us evolve our music over time,” 113’s Mokobé adds. “It’s thanks to him that there are no limits, no bars, no borders for us … This is what his music was all about; no bars, no barriers, no border.”