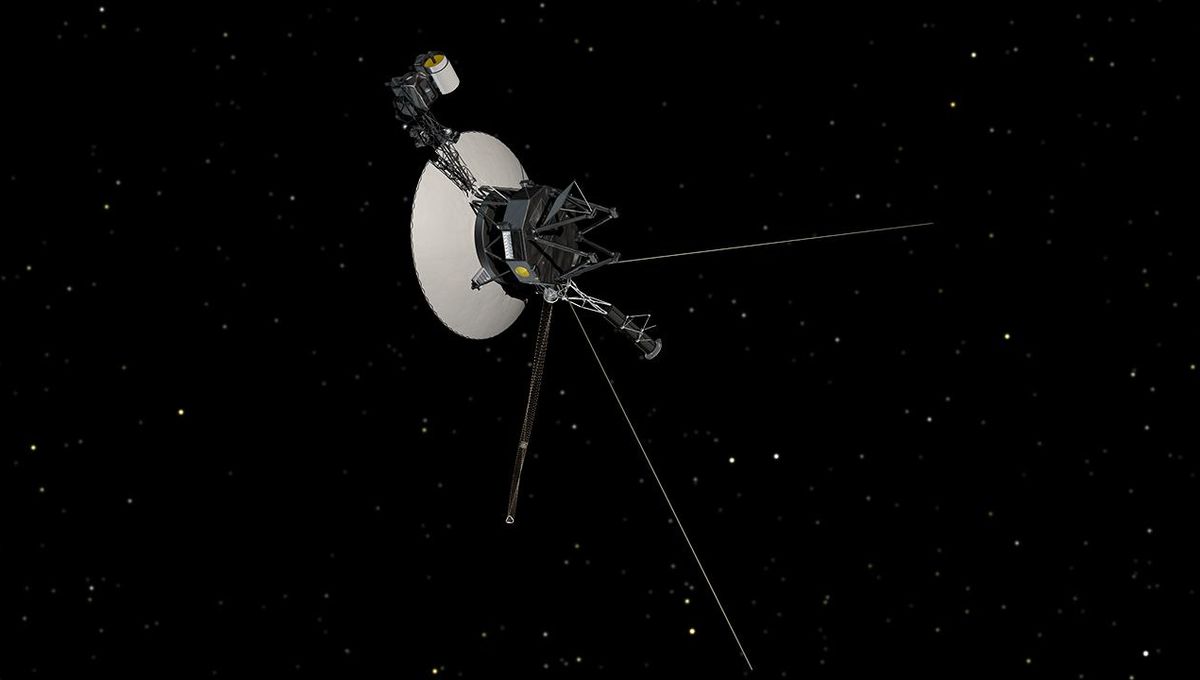

In August 1977, NASA launched Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 into space with no idea they would go on to become the space agency’s longest-running mission. The twin probes would end up visiting Jupiter and Saturn, and Uranus and Neptune, respectively, before going on to become the first (and only) human-made objects to get to interstellar space in August 2012. Nearly 50 years on, they continue to go strong. Over the last few years, the Voyager team has performed some impressive maneuvers from an unfathomable distance to keep them working, so to mark their continuous success, we spoke to Dr Linda Spilker, Voyager Project Scientist, about these extraordinary spacecraft, what they have achieved in their 48 years of travel, and what they are doing next.

Speaking to someone running the science on a mission is always a pleasure. You get an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the cutting-edge work happening on another world or in deep space. And there is no deeper space for direct exploration than interstellar space, where the Voyager probes currently are. There is another reason, though, why speaking to Dr Spilker was special. She was there at the very beginning of this extraordinary mission.

I think in that single first flyby by Voyager 1 of the Jovian moons, it sort of shattered our idea of just what a moon could look like.

Dr Linda Spilker

“I started working at the Jet Propulsion Lab in January 1977, and they gave me a choice: did I want to work on a mission that would be launching in the fall called Voyager or the Viking extended mission,” Dr Spilker told IFLScience in our exclusive video interview below.

“Of course, my first question was: ‘Well, I’ve never heard of Voyager. Where’s Voyager going?’ and they said Jupiter and Saturn, and if all goes well, on to Uranus and Neptune. I remember as a small child getting a tiny telescope out and looking at Jupiter and the rings of Saturn, and so I said, ‘Sign me up, I want to work on Voyager, I’d love to get close-up views of these places!’”

Despite the numbering, it was Voyager 2 that launched first, and Dr Spilker saw that happen in person. She stayed with the mission for more than a decade, until after the Neptune flyby of Voyager 2 in 1989. These spacecraft were game changers when it comes to our knowledge about the outer planets. No other probe has been sent to Uranus and Neptune since. We couldn’t help but wonder what the expectations were at the very beginning.

“Initially, when Voyager launched, it was just planned to be a 4-year mission, which would have been the two flybys of Jupiter and two flybys of Saturn,” Dr Spilker told IFLScience. “That was the Voyager Prime mission.”

The plan was to use the information from Voyager 1, which, despite the later launch, got to the planets faster (thank you, celestial mechanics), to then inform follow-up observations from Voyager 2. There were major breakthroughs by both spacecraft, but something blatantly obvious from the very first encounter with Jupiter is that moons in the Solar System don’t all look the same. Expecting something like our Moon, Voyager found the icy and active surface of Europa and the volcanic Io.

“I think in that single first flyby by Voyager 1 of the Jovian moons, it sort of shattered our idea of just what a moon could look like,” Dr Spilker explained. “We had to sort of open up our imaginations to what the possibilities might be and then start to try and explain what Voyager had actually seen.”

Another moon is responsible for the Voyager 2 mission being directed towards Uranus and Neptune: Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Voyager 1 flew by the moon in 1980 and discovered its hazy, dense atmosphere. Since neither spacecraft was equipped to peer through it, the mission team decided to let Voyager 2 skip meeting Titan, giving it a chance to travel toward Uranus and Neptune. Don’t worry, though, Dr Spilker had ample time to work on Saturn, becoming involved with the Cassini mission right after Voyager and eventually becoming the mission’s Project Scientist between 2010 and 2019.

We were curious if Dr Spilker at the time thought that Voyager would continue to go strong for many decades after launch, decades after she had left the program to work on Cassini.

“I personally didn’t because we had heard all along that once we were past the first four years of the mission, the Voyagers were now getting to be quite old,” Dr Spilker explained. “That was the story pretty much through the decades as the Voyager mission continued well past the Neptune flyby; it’s probably just a few more years that the Voyagers will last. And yet they just kept on going. Any problems that came up, a very clever group of engineers would solve.”

Once the Voyagers can no longer communicate with Earth, they become our silent ambassadors. In about 40,000 years, each Voyager will pass relatively close to another star. We don’t know for sure if those stars have planets, much less inhabited planets, but it’s a chance for us to send our message in a bottle out into the cosmos.

Dr Linda Spilker

And there have been several problems, for which the solutions have indeed been incredible. Even more incredible given that Voyager 1 is almost a whole light-day away from Earth, so it takes a long time – 23 hours each way – to send messages and wait for a reply. Even at this distance, the mission continues with more scientific data coming to Earth.

One day, the Voyagers will stop communicating. It will be a very sad day for this extraordinary program, which has radically altered what we know of the Solar System and beyond. But Dr Spilker still has words of hope about that event, which we hope is in the far future!

“The Voyager mission is truly iconic. What I really like about both Voyagers is that they each carry a golden record. That golden record has the sights and sounds of Earth, about a hundred pictures and hello in different languages,” Dr Spilker told IFLScience.

“Those records, once the Voyagers can no longer communicate with Earth, then they become our silent ambassadors. In about 40,000 years or so, each Voyager will pass relatively close to another star. We don’t know for sure if those stars have planets, much less inhabited planets, but it’s a chance for us to send our message in a bottle out into the cosmos.”

For now, the Voyagers will continue taking a little piece of Earth, a piece of humanity, further than we’ve ever been before, and who knows what they’ll encounter in the future.