Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

In my first article, I described how Bach’s Cello Suites, Violin Sonatas and Partitas should be interpreted as polyphonic pieces, even though they were written for monophonic instruments. The idea of ‘implied’ polyphony is, of course, not new. A lot of interesting and valuable research has already been done in this case. However, the majority of the analyses considers this music from a horizontal or a vertical point of view. The idea of consistent voice leading in these works is often overlooked. Bach’s implied polyphony is not accidental or random; the contrapuntal network is systematically structured. It extends consistently throughout the entire piece and sometimes goes far beyond what the eye and ear can perceive. I challenged myself to go a step further with the aim of connecting the vertical harmonic elements and the horizontal lines into a real contrapuntal tapestry.

In this article, I would like to apply my approach to excerpts from Bach’s Corrente of the famous Violin Partita no.2 (BWV 1004).

When analysing Bach’s solo violin works harmonically, the first task is to reduce the music to a series of functional chords. However, since the violin accompanies itself and Bach’s mindset is polyphonic (each chord note arises from a previous one and leads to the next), the real challenge lies in connecting the corresponding notes while respecting the rules of counterpoint. And this is where the real magic happens. By reducing the music in this particular way and paying attention to Bach’s pragmatic considerations, a contrapuntal fabric emerges. The often three-part framework surfacing in that way is no coincidence: underneath Bach’s natural and spontaneous music lies an extremely well-organised network. This is true polyphony, albeit in disguise. It is very important that the performer brings the underlying structure to life.

Underneath Bach’s natural and spontaneous music lies an extremely well-organised network. This is true polyphony, albeit in disguise

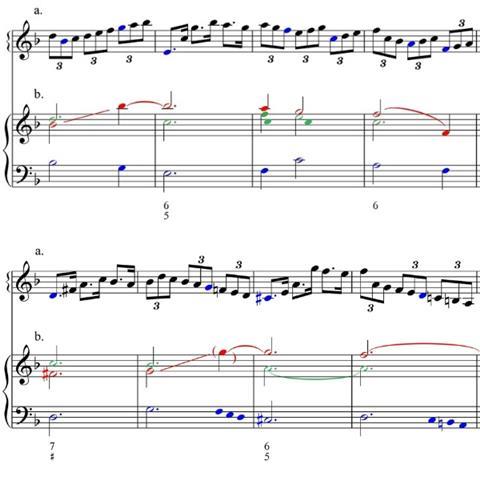

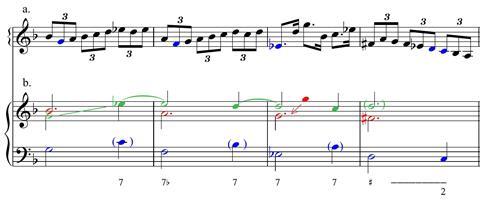

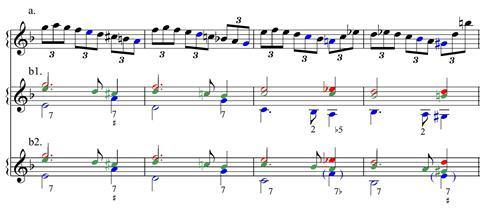

Looking at the opening bass line of the Corrente, one immediately notices the similarity to the Allemande and the Chaconne. This creates unity within the Partita, which is a sequence of different dances. The contrapuntal reduction exposes a lot of descending patterns, such as the downward line in the upper voice (red) in m.1 to 4 (Ex.1). From m.5 to 8, Bach introduces another descending line, and again in m.9 to 12 (Ex.2). The smooth and structured voice leading is clearly noticeable in the different voices and throughout the entire piece.

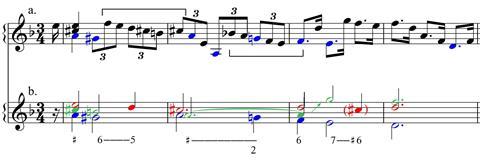

One of the things that is often overlooked and that I would like to draw attention to, is Bach’s use of octave leaps in the underlying voice leading, especially in the middle and the higher registers. These leaps not only serve a dramatic and aesthetic purpose, they are often pragmatic by nature. The violin is a small four-stringed instrument with limited polyphonic capabilities. Octave leaps are often necessary to maintain the underlying conceptual motion of the implied voices. Examples of these voicing leaps include measures 4, 5 and 8 (Ex.1), 9, 12 and 14 (Ex.2), 27 (Ex.3), 32 (Ex.4). In m.4, for instance, the upward leap in the green voice (from A3 to A4) is necessary because a further descending line from G3 (the lowest playable note on the violin) to F3 would be impossible on the instrument. In other cases, Bach must always ensure that the upper voices do not interfere too much with the lower fundamental bass notes. After all, Bach’s music is built upon a Generalbass.

Once we carefully consider these particular pragmatic compositional choices, the inner contrapuntal framework becomes even more clear and transparent. It is very important to be aware of these voice crossings when practicing and performing these works.

In his Sonatas and Partitas, Bach uses imitation at various levels to suggest a polyphonic dialogue. In m.15 (Ex.2), for instance, the red voice echoes the motif of the green voice (m.13) in the upper fifth. An analogous example -however, with answer in the lower fifth- can be found in m.25-26 (Ex.3). These and other examples reconfirm the idea of a well thought-out underlying part-writing. Again, the executor has to keep these structures in mind.

Sequences, such as m.32-35 (Ex.4) and m.40-43 (Ex.5), are basically compound melodies built upon the circle of fifths. Bach reinforces the harmonic tension by adding minor or major sevenths.

A violinist could emphasise all the above-mentioned structures, functional notes and voice leading through specific articulation. The use of down or up bow, the phrasing, the bow pressure, the attack, slight dynamic changes, agogic accents: they can all structurally spice up the music and bring out the underlying contrapuntal fabric.

My approach is the result of a kind of simultaneous integrative analysis and can be applied to the other Violin Sonatas and Partitas. I’m convinced that these reductions can be a thought-provoking and useful resource for any violinist, especially when practising these masterpieces. My analyses can be found on my YouTube channel, The Lost Art of Counterpoint.

Feel free to contact me (laurent_matthys@hotmail.com) if you believe that my research could be of value. I strongly believe in the importance of mutual cooperation between performers and musicologists, especially in this niche area. It would be a great honour to give interactive masterclasses linking music theory to practical implementation.

Laurent Matthys

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

In the second volume of The Strad’s Masterclass series, soloists including James Ehnes, Jennifer Koh, Philippe Graffin, Daniel Hope and Arabella Steinbacher give their thoughts on some of the greatest works in the string repertoire. Each has annotated the sheet music with their own bowings, fingerings and comments.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.