The Space Age began on October 4, 1957, with the launch of the Soviet Sputnik 1. Months later, NASA answered with Explorer 1. Since then, over 6,900 payloads have launched into space — orbiting Earth, sending back climate data, enabling GPS, or exploring the cosmos.

Others sent humans into orbit, to the Moon, and rotating crews to the International Space Station (ISS). These missions have advanced astronomy, cosmology, and our understanding of space (and our place in it); however, some missions aimed to send something immeasurably important to space: cultural artifacts. Since the 1970s, space agencies have deployed spacecraft that have taken a piece of human culture to deep space.

Many more have been planned or are already on their way. These missions represent humanity to the cosmos, which could include extraterrestrial civilizations someday. A walk down memory lane is needed to understand their true importance.

‘For All Mankind’

When people think of the period from 1957 to 1973, they generally picture two superpowers locked in a state of competition and one-upmanship. This largely consisted of two parallel races – the nuclear arms race and the “Space Race.” While true, there was also a newfound spirit of cooperation and celebration, where both sides took pride in the other’s achievements. This is epitomized by the Apollo 11 Plaque, which contained the inscription:

“HERE MEN FROM THE PLANET EARTH

FIRST SET FOOT ON THE MOON

JULY 1969 A.D.

WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND.”

In essence, there was an understanding that humans going to space were doing so for all humanity and acting as representatives of Earth. The same spirit motivated the many artifacts launched into space during (and since) the Space Age. These artifacts often served as time capsules, marking key milestones and reminding future generations of historic achievements (like the Apollo 11 plaque). In other cases, they were potential messages for other civilizations that might encounter them someday.

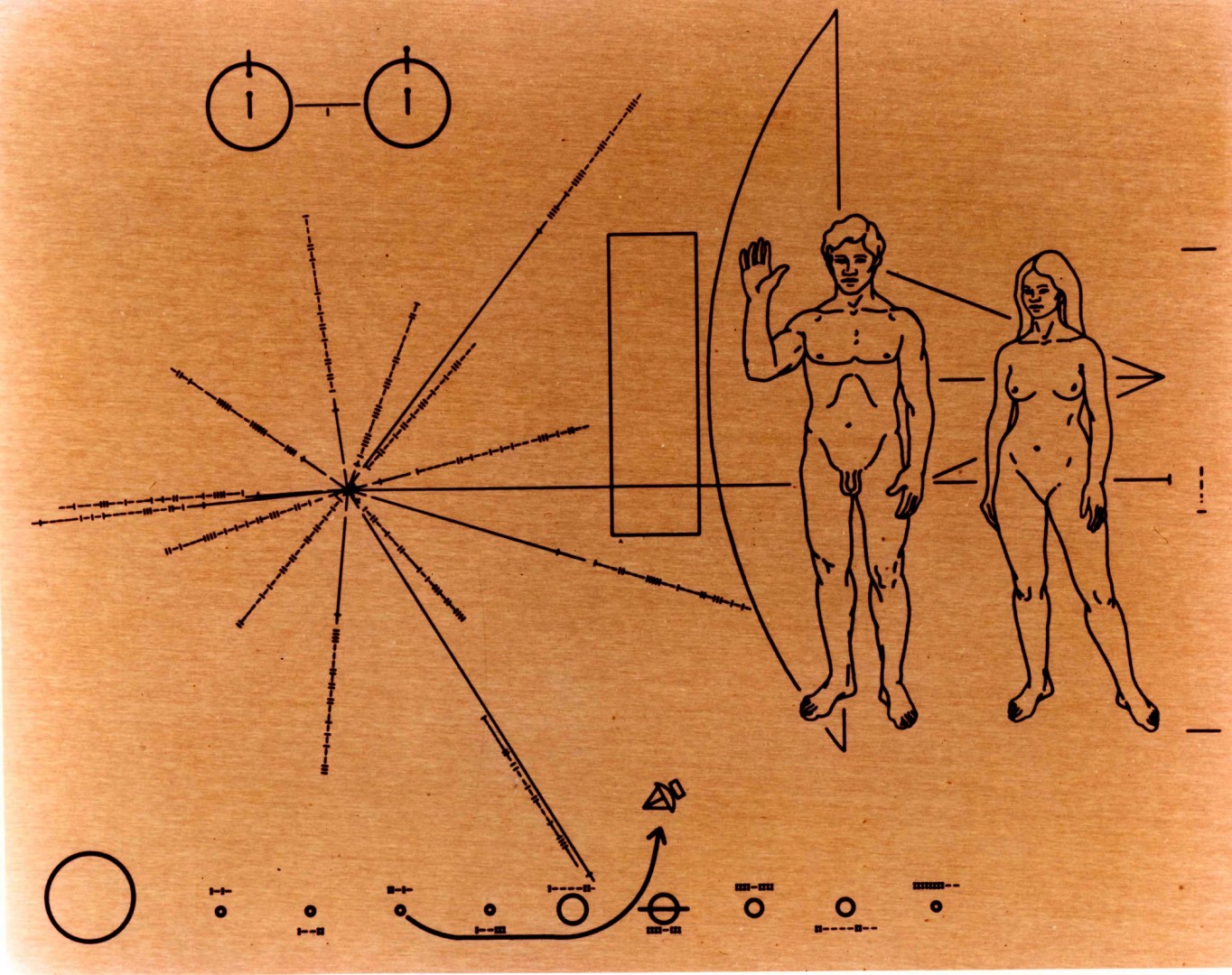

The Pioneer Plaques

The Pioneers 10 and 11 probes, launched in 1972 and 1973 (respectively), became the first missions to explore the Asteroid Belt, Jupiter, and Saturn. They were also the first probes to achieve escape velocity from the Solar System. As such, NASA decided to include a message from humanity with these missions, since an extraterrestrial species might someday find them. The idea was first suggested by journalist Eric Burgess (who chronicled the Pioneer Program) and famed science communicator Carl Sagan.

These efforts resulted in the Pioneer Plaques, a pair of gold-anodized aluminum plates measuring six by nine inches (22.86 cm by 15.24 cm). The plates contained an engraved pictorial message identifying the probes’ time and place of origin and who sent them. From top to bottom, left to right, the message included the following:

- The hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen (the most common element in the Universe)

- The location of the Sun based on its distance from 15 pulsars

- A depiction of the Solar System, showing the flight path of the probe from Earth

- A silhouette of the spacecraft

- Figures of a naked man and a woman, with the man raising his hand in greeting

The Pioneer 10 and 11 are two of five missions that have left the Solar System in the past 50 years. The former is headed towards the star Aldebaran, roughly 65 light-years away in the Taurus constellation, and will take more than two million years to reach it. The latter is headed for the Aquila constellation and will pass near one of its stars in about 4 million years.

The Voyager Golden Records

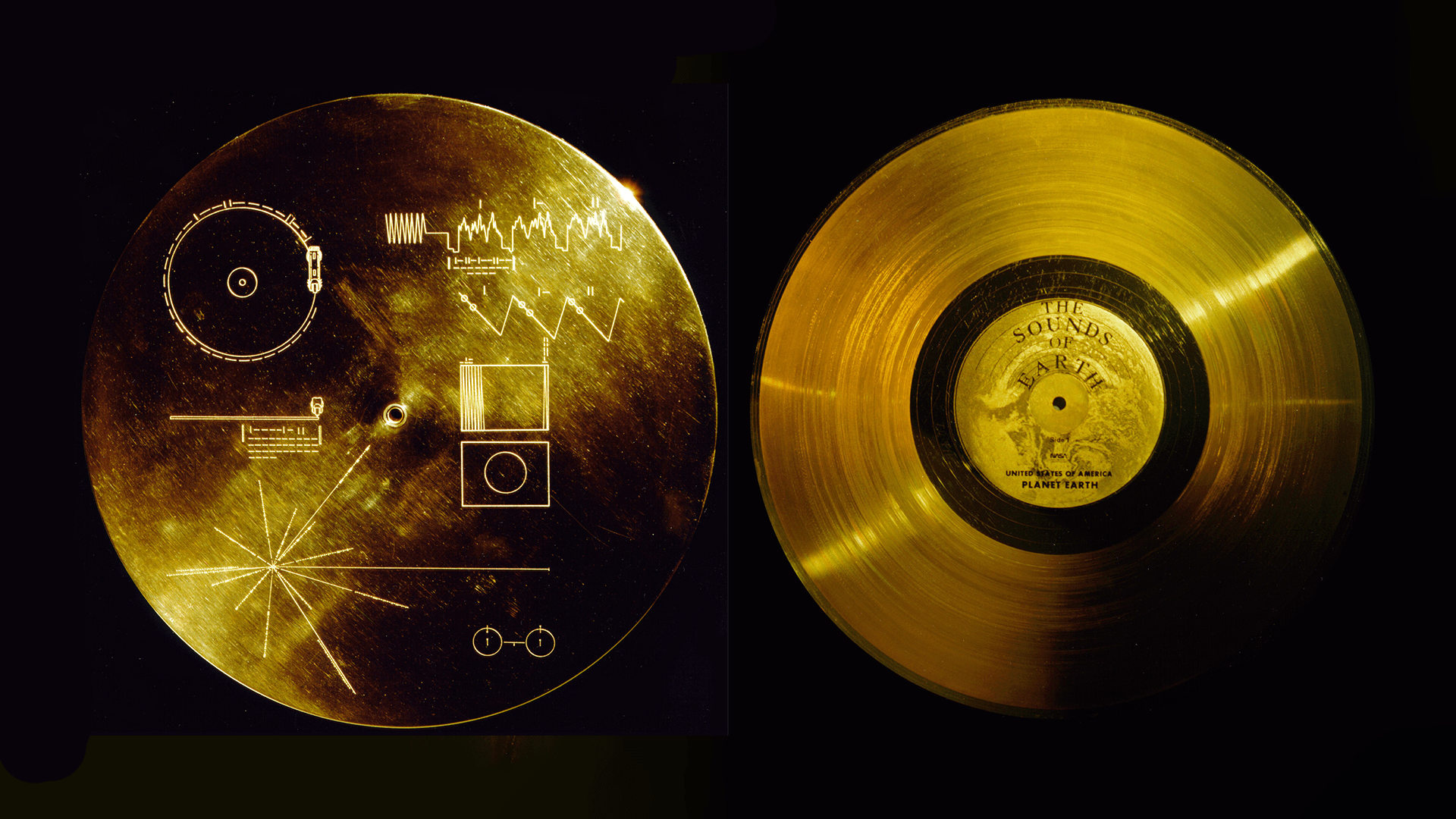

Building on the Pioneer Plaques, NASA included a more ambitious message on the twin Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. These missions were also destined for the outer planets and would achieve escape velocity from the Solar System. This new message was known as the Voyager Golden Records, a series of 12-inch (30.5 cm) gold-plated copper disks containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

The outer case included pictograms showing where the probes came from and instructions on how to play the record. This included a drawing of the phonograph and the stylus in the correct position to play the record from the beginning. Around it, in binary arithmetic, is the time it takes for the record to achieve one rotation (3.6 seconds), indicating that the record should be played from the outside in. Below is a side view of the record and stylus with a binary number showing the time it takes to play one side of the record – about an hour.

The images in the upper right portion of the cover were designed to show how to reconstruct pictures from the recorded signals. The drawing immediately below shows how these lines are to be drawn vertically, that there are 512 vertical lines in a complete picture, and a replica of the first picture on the record, allowing the recipients to verify that they are decoding the signals correctly. The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map, like the ones included in the Pioneer Plaques.

A drawing of the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen is also included. This time, it provides a time scale for the images on the cover and in the decoded pictures. The cover also contains an electroplated sample of uranium-238, which has a half-life of 4.51 billion years. In this sense, the element acts as a radioactive clock, allowing the recipients to calculate how long the probe has been in space.

These records were also the brainchild of Carl Sagan. They were intended to be both a possible message for extraterrestrials and a time capsule, given that they might be found by future generations of humans rather than an advanced civilization. On August 25, 2012, Voyager 1 made history by becoming the first probe to enter interstellar space, and was joined by Voyager 2 on November 5, 2018.

The Arecibo Message

In addition to plaques and records that served as messages from humanity, Earthlings have also sent transmissions that have earned their place in the annals of spaceflight history. While not tangible in the same sense as gold-anodized images and recordings, these historic attempts to communicate with the cosmos are no less meaningful.

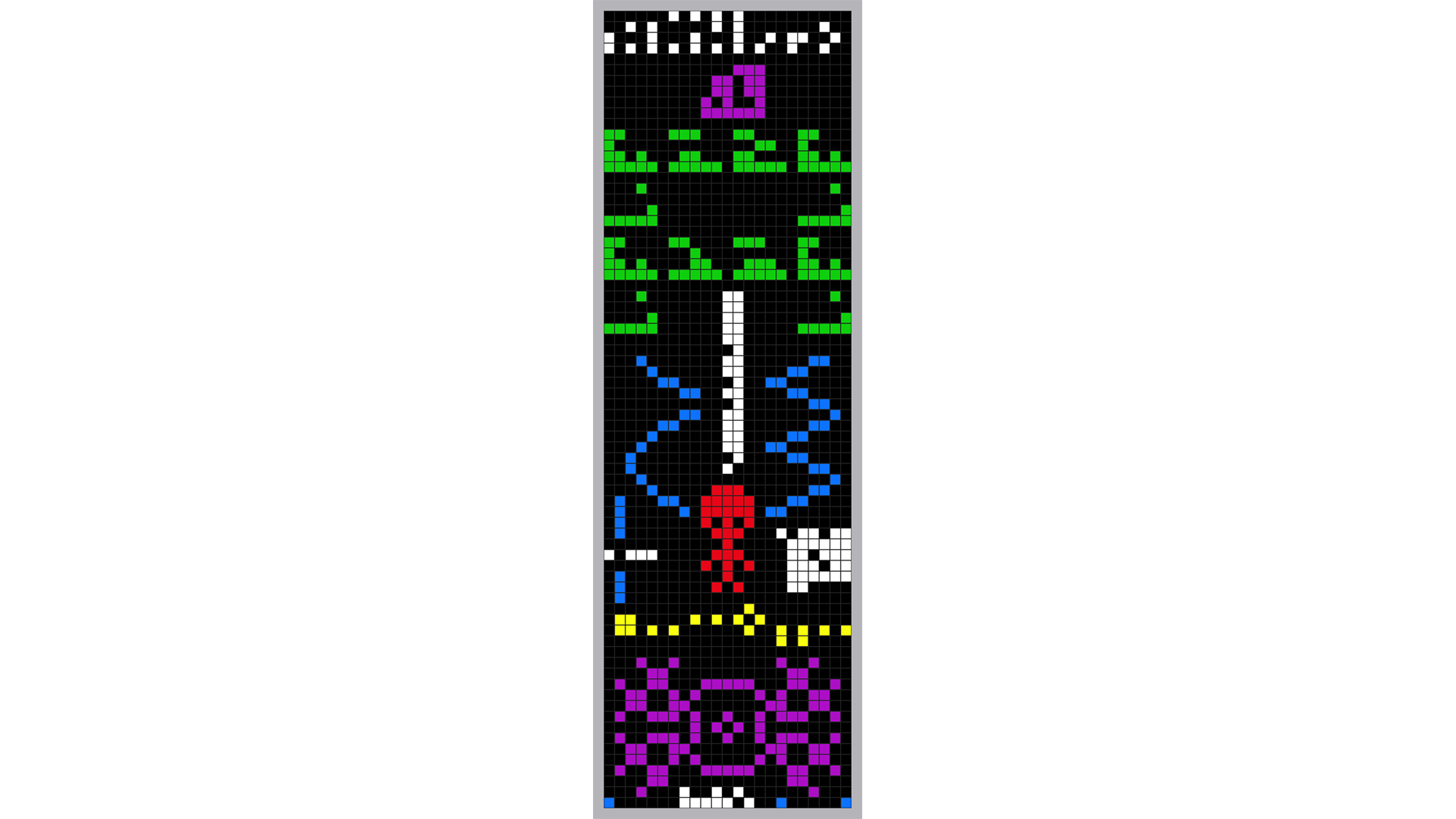

In the early 1970s, Cornell Professor Frank Drake (inventor of the Drake Equation) organized the first campaign to compose a message destined for space. Roughly a decade before, Drake led the first Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), known as Project Ozma. This effort, known as the Arecibo Message, relied on the Arecibo Observatory, the massive radio antenna in Puerto Rico that was officially retired in 2022.

The Arecibo Message used the observatory’s megawatt transmitter and 305-meter (1000-foot) antenna to send a 20-gigawatt broadcast at 2380 MHz and an effective bandwidth of 10 Hz towards the globular cluster M13 located 22,200 light-years away. This cluster is made up of 300,000 stars and is estimated to be 11.65 billion years old, so it was considered a likely place for an extraterrestrial civilization. Drake and Carl Sagan, along with other prominent astronomers, composed the message, which was transmitted on November 16th, 1974.

The message lasted three minutes and consisted of a 1679-binary digit picture, arranged rectangularly into 73 lines of 23 characters per line. Whereas 73 and 23 are prime numbers, 1679 is the product of their multiplication. This decision was deliberate since it would make the message easier for an alien civilization to decode. The decoded message contained a series of scientific, geographical, biological, and astronomical information in different colors. These included:

- A counting scheme of 1 to 10 (white)

- The atomic numbers for hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus, which make up DNA (purple)

- The chemical formula of the four purines and pyrimidine bases that make up DNA (green)

- An image of the DNA double helix and an estimate of the number of nucleotides (blue and white, respectively)

- A stick-figure of a human being (red), our average dimensions (blue/white), and the human population of Earth (white)

- A depiction of the Solar System, indicating that the message is coming from the third planet (yellow)

- A schematic of the Arecibo Observatory and its dimensions (purple/white and blue)

This message was not intended as an invitation to converse, but as a demonstration of humanity’s technological abilities, scientific knowledge, and location in the galaxy to a possible extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI). In short, the message declared, “We are here!” in a loud radio transmission that might reach another civilization someday.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg! Please tune in for the second part when we’ll discuss other artifacts and messages that were sent to space. We’ll also explore the controversy surrounding sending messages, which is part of a now-growing field known as Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI).