Bruce Springsteen digs through his discarded material and releases seven albums in the Tracks II: The Lost Albums box set. Listening to this is either bittersweet or disheartening, depending on your taste. If, in 1998, the first installment of Tracks was a treasure trove of rejected songs that deserved to be on his best 1970s albums, almost 30 years later the material simply reveals how he once ventured down erroneous paths, and half-heartedly at that. Electronic arrangements, debatable incursions into country, orchestral pop and Mexican heritage all diverted him momentarily from producing the sounds that filled stadiums and turned him into The Boss.

Springsteen is not the only Anglo rock star sharing material discarded as commercially useless or simply mediocre. Curiously, someone as jealous of his privacy as Bob Dylan was the first to breathe new life into ditched material. The reasons are varied and usually associated with money; there are always several thousand fans who acquire anthological artifacts at prohibitive prices. Then there is the extension of copyright involved in publishing recordings that would otherwise enter the public domain. There is also a technological explanation regarding the introduction of the CD in the mid-eighties – a format that offered twice the duration of a vinyl LP, and whose properties and measurements facilitated the preparation of exhaustive anthologies.

The emergence of a historic Dylan bootleg, Great White Wonder (1969) during the counterculture era laid the foundations for this trend. It included home recordings of his songs, not live takes recorded at concerts, as would be the tendency in the pirate industry of the following years. It was a trend that began with another Dylan treasure, Vol. 4 Live 1966: The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert (1998), a two-disc live album that reflects the schism between folk and rock.

During the 1970s, an underground industry of illegal vinyl flourished that released concerts and studio sessions of rock legends: The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin and AC/DC, etc. Some clever artists, such as Frank Zappa, counterattacked in the eighties by reissuing the most successful pirates on their own labels. The following two decades raised sales figures, and auditory quality, thanks to the more manageable CD, flooding the market with sweet recordings edited thanks to an alleged legal loophole. Today, in stores and on platforms you can find concerts on vinyl with the subtitle Radio Broadcasts, with the copyright of radio broadcasts dwelling in a dubious limbo.

In 1985, Dylan once again got ahead of the pack with the release of his album Biograph, two thirds of which consisted of a selection of his best songs while a third consisted of unreleased ones. Biograph was an early example of the boxset trend – luxurious boxes offering a compendium of an artist’s discography with additional rarities. These were dedicated to Sam Cooke and James Brown, Elvis Presley and Waylon Jennings, The Who and The Beach Boys, The Band and Booker T. & The MGs, etc. In the new millennium, as sales of physical formats declined, the industry ceased to see this format as a profitable business, despite the fact they were compiled with catalog collections, without the expense of a new production.

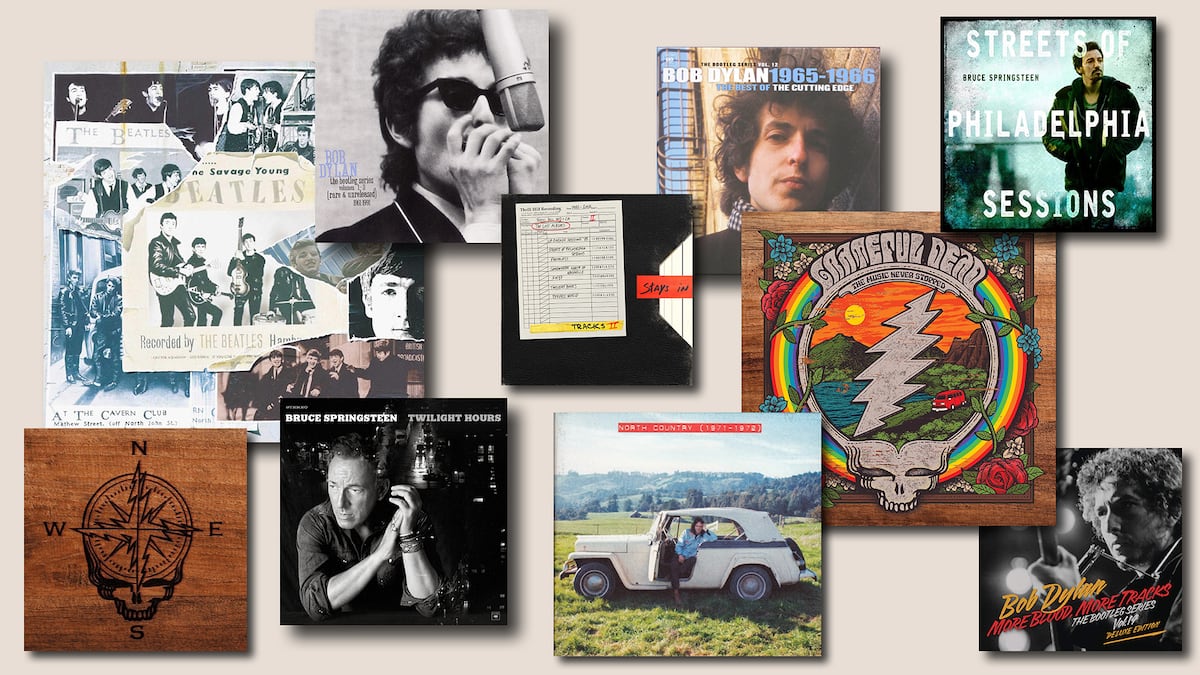

Dylan began another currently common trend with The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3: Rare & Unreleased 1961-1991. The series of former pirated publications is now in its 17th volume, but not all installments offer the historical value of Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966 (2015), an artifact released in different configurations, it showcases the shift to electronic sounds that transformed rock. For $600, a collector could buy a box with 18 records and 379 studio takes; in other words, absolutely everything that was recorded during those years. Such a mammoth collection exists because Dylan’s record company predicted 500 people would be willing not only to pay the price but to listen carefully to every note, every difference in the 20 takes included from Like a Rolling Stone. There were also editions of six albums and a double CD, enough to get an idea.

Is it valid to release the sketches and failed attempts that resulted in the music that had a social impact and historical resonance as well as an artistic one? Does releasing it distort the work or, on the contrary, does it magnify it by showing the process that shaped it? What was going through Dylan’s mind when he released Infidels (1983), and decided to leave out Blind Willie McTell, one of his most popular songs in recent years? Wouldn’t it be better to wait until the artist is no longer with us to undress his creative process? Or is baring it during their lifetime necessary to certify their consent to the project, thereby validating it for the listener? Although, as Lou Reed said: “They call them discards for a reason.”

Other rock legends, such as The Beatles, have not given their archives the same treatment. They first gave the world a glimpse of what was in them in 1995 with the three double volumes of Anthology, including unreleased material, outtakes and alternate versions of their most popular songs. Those albums were part of a larger operation that included a documentary series broadcast on TV and a book that gave them a voice in a story obviously shaped by its unofficial origin. Listening to a A Day in the Life made with discarded material from Sgt. Pepper is undoubtedly attractive, although it does not live up to the version released at the time. This is firstly because if the group and its producer George Martin agreed on the actual released album, it was for a reason. Secondly, and more importantly, because by listening to it hundreds of times we have made the album our own, attaching to it memories and different emotions. Once delivered by the artist, a song is chiseled into the listener’s unconscious. That is the power of music.

The Beatles were stingy, then, compared to Dylan. But the group would balance this out by allowing their living members and the heirs of Lennon and Harrison Get Back (2021), a documentary that showed the last sessions of the group, revisited by filmmaker Peter Jackson. There was no record editing, but there was a quantum leap in the audiovisual preservation of the creative process of a musical group in a recording studio.

Neil Young is another artist who has gone for releasing tracks from his archives, practically matching Dylan in his dedication. His monumental operation The Archives – large boxes containing audio and video discs, plus reams of printed material – will offer future generations a complete overview of his life and work. It began with The Archives Vol. 1 1963-1972 (2006) and has reached a third volume, published in 2024, which deals with the controversial period from 1976 to 1987.

In the eighties, Young released recordings where he fused his country and rock roots with primitive electronic sounds and filtered voices. His label promptly filed a lawsuit against him for not recording albums in line with his most recognizable work, as if the artist’s job was to repeat themselves rather than follow their instinct.

Young was hesitant, and smoked too much marijuana, completing albums that were discarded either by the record company or by himself. Rescued in recent years, they provide details that any Neil Young scholar will appreciate. For example, Hitchhiker (2017), recorded in the summer of 1976 with his trusted producer David Briggs, was rejected by the record company on the grounds that those were demos and should be re-recorded with instrumental accompaniment. Eight of the 10 songs would appear on later official albums.

Between 1971 and 1974, Homegrown (2020) was compiled – another acoustic album that Young decided to shelve in 1975 as its songs were painfully intimate, written after a painful separation. Curiously, he would instead release Tonight’s the Night, an abysmal mourning for two members of his crew who died from an overdose. A rocky patch with his wife, Pegi was the reason that an album recorded with Crazy Horse was ditched in 2000, only to be released 20 years later entitled Toast in a nod to the Californian studio where it was recorded.

In 1977 Chrome Dreams (2023) was to be Young’s new release, but it was also aborted. A copy of this would be pirated repeatedly for decades; The repertoire included some of his best seventies’ songs, some rescued in later albums, others forgotten. Also from 1977 are tracks included on Oceanside Countryside (2025), which would have preceded the released Comes a Time. But isn’t it repetitive to find edited versions of the sessions that gave rise to the essential Zumaof 1975 on Dume (2024), with Zuma marking one of the peaks of his collaboration with the now defunct Crazy Horse?

Let’s go back to Springsteen. Is Tracks II as disappointing as it first seems? Britain’s most prestigious music critics have rated it highly and consider these seven albums to be valuable material. It is, artistically and commercially, forgotten material by a rock legend whose hallmark was addressing social and political realities. And, although musically, these songs cannot be compared to his most outstanding work, they reveal the proletarian and dark side of the American dream he embodies. Now there’s Tracks III, with five more unreleased albums, and the mythologized Nebraska recorded with the E Street Band, which at the time was shelved as unsatisfactory.

Could it be that rock’s story is coming to an end – a story which in the sixties was dominant industrially and culturally, creating a community of young people who had a meeting point, a language of their own with which to question the system, a network of networks long before the internet arrived. The emergence of these musical archives helps to review and understand the cultural flowering that produced this music, today degenerated into yet another virtual business.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition