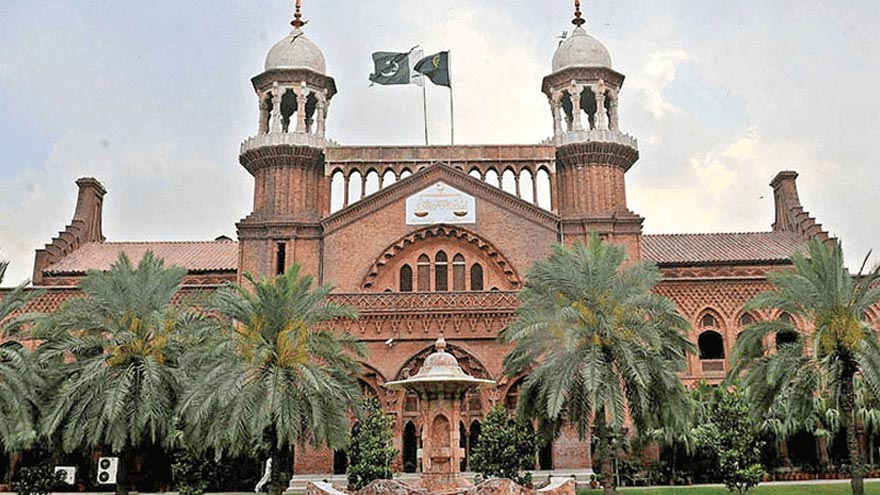

LAHORE (Dunya News): The issue surrounding the demolition of Data Darbar pet market has resurfaced in Lahore High Court (LHC) in the form of a new constitutional petition.

The first petition had been filed by…

LAHORE (Dunya News): The issue surrounding the demolition of Data Darbar pet market has resurfaced in Lahore High Court (LHC) in the form of a new constitutional petition.

The first petition had been filed by…