The electrification of India’s economy remains a work in progress, mainly because transmission and distribution are in the hands of inefficient public utilities. But large business groups capable of generating and distributing their own electricity could upend the status quo.

WASHINGTON, DC/CHENNAI – As the use of energy-guzzling AI grows, the countries that embrace renewables will gain an obvious competitive advantage. And on this front, China has established a substantial lead. According to the Financial Times, the country is on track to source 50% of its power from renewables (mainly solar and wind, but also nuclear, hydro, and battery-storage systems) by 2028.

By comparison, India’s efforts to promote renewables, while commendable, have yielded modest results. As the figure below shows, despite meeting its 2030 target for adding renewable-energy capacity five years ahead of schedule, India still lags behind its emerging-market peers – including Brazil, China, Mexico, Pakistan, and Turkey – and most advanced economies in terms of the share of solar and wind in total electricity generation.

Over recent decades, India’s energy landscape has changed dramatically, moving from scarcity to relative abundance – even for the rural poor. Blackouts, erratic supply, and the use of polluting diesel generators are a thing of the past. But the electricity revolution, and the transition to renewables, remains a work in progress.

One reason for the slow pace is that electricity transmission and distribution are mostly in the hands of public-sector incumbents that are highly inefficient, deliver consistently negative returns, and need to be bailed out periodically by governments and public financial institutions. Domestic and foreign private-sector players are reluctant to work with these loss-making utilities, which India’s 28 states largely oversee and regulate, because of the associated credit risks.

Populist policies only compound the system’s inefficiencies: nearly every state government provides free or subsidized electricity – which we estimate at about 1-1.5% of GDP annually – to households and farmers, resulting in significant budget shortfalls. To recoup some of their lost revenues, utility operators charge industrial and commercial users substantially higher prices for electricity, penalizing India’s manufacturing sector.

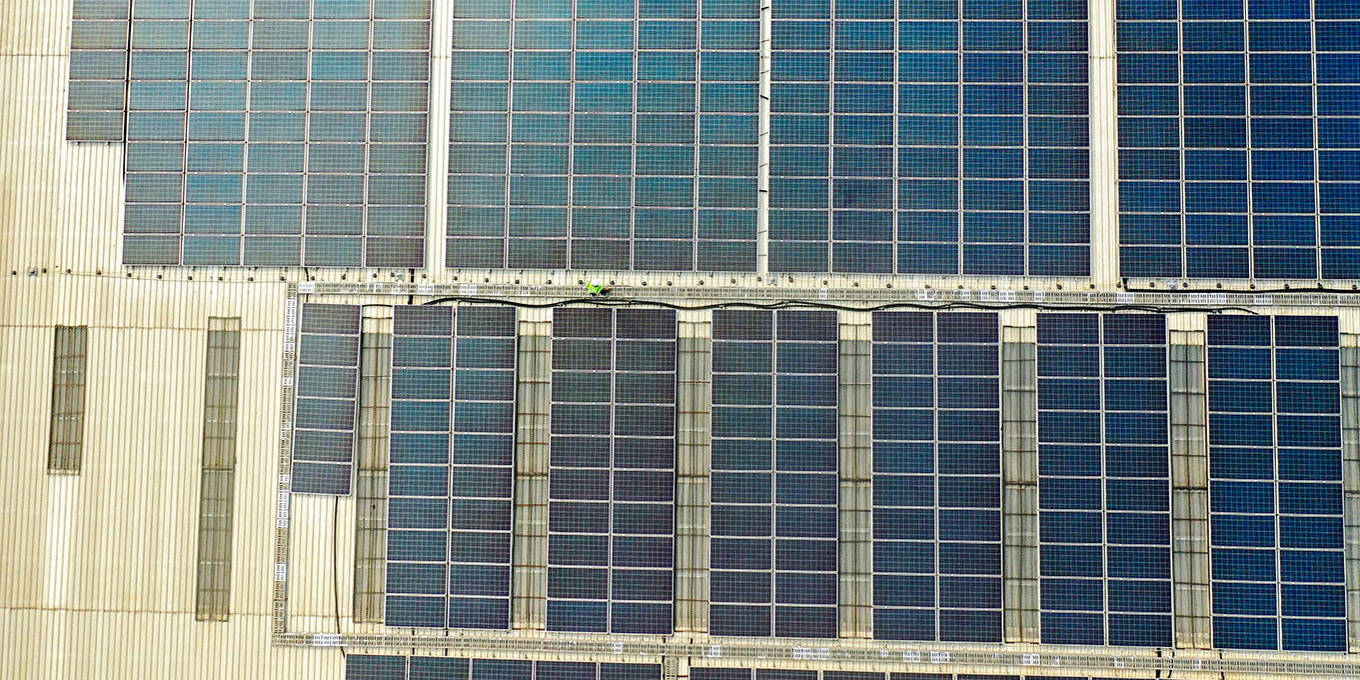

Radical institutional reform of electricity distribution and a backlash against populism may be slow to come, but there are glimmers of hope for India’s clean-energy future. For starters, industrial and commercial users are increasingly producing their own renewable power. In Tamil Nadu, for example, such “captive” generation accounts for more than 28% of total industrial electricity consumption. Intermittency and high storage costs often force these firms to rely on public utilities for their power needs when the sun isn’t shining.

HOTTEST SALE OF THE SUMMER: Subscribe now for 40% less

Our Summer Sale has begun. Get more access to Project Syndicate, starting at less than $5 per month for your first year. Click the button below to view our subscription offerings.

But that is starting to change. Some large business groups are leveraging declining solar and storage costs to generate and consume their own electricity, thereby exiting from the public system altogether. These firms have used their clout to reshape the policy and regulatory framework in favor of such “captive capacity,” while a string of legal rulings has also facilitated the process.

This is reform by stealth, because the public monopoly is slowly and subtly being undermined. To head off opposition from the electric utilities, and to secure regulatory approval, these projects are being presented as just another form of captive activity – namely, generation to meet an entity’s own consumption needs.

But it is easy to envisage large private players eventually servicing a wider range of consumers: first their suppliers, then their suppliers’ suppliers, and so on. If this parallel structure becomes more efficient, cheaper, and greener, demand will soar, at the expense of the public monopoly. For this strategy to be profitable, business groups will need to be large enough to bear the enormous costs of investing in the required infrastructure, but not so large that they pose an immediate threat to the public incumbent.

If this happens, the public monopolies will have fewer industrial consumers to overcharge – and substantially less revenue. They can respond in one of two ways. They can reduce subsidies to non-poor households, provide cheaper power to the manufacturing sector, and become more efficient and service-oriented. Or they can maintain the status quo, shrinking in size while being kept afloat by government support.

India’s history shows that it could go either way. When the country opened its economy in 1991, some public-sector incumbents, for example in steelmaking, became more efficient. By contrast, the old telecoms operators continue to limp along, relying on repeated bailouts from the central government. Fortunately, the dynamic private sector now dominates the telecoms market.

To be sure, stealth reform aided by regulatory favors has a high cost. But an unresponsive and loss-making public electricity system that has failed to deliver for over 75 years imposes even greater costs in terms of higher energy prices, a stunted manufacturing sector, and a delayed green transition. India’s electric utilities face a stark choice: reform or irrelevance.