Study design

This multicenter cluster RCT with a special case of a stepped-wedge design with two arms and one step used a PAR approach in Dutch nursing homes and is part of the RID study. The full study protocol has been published elsewhere [45]. This report follows the CONSORT guidelines [46].

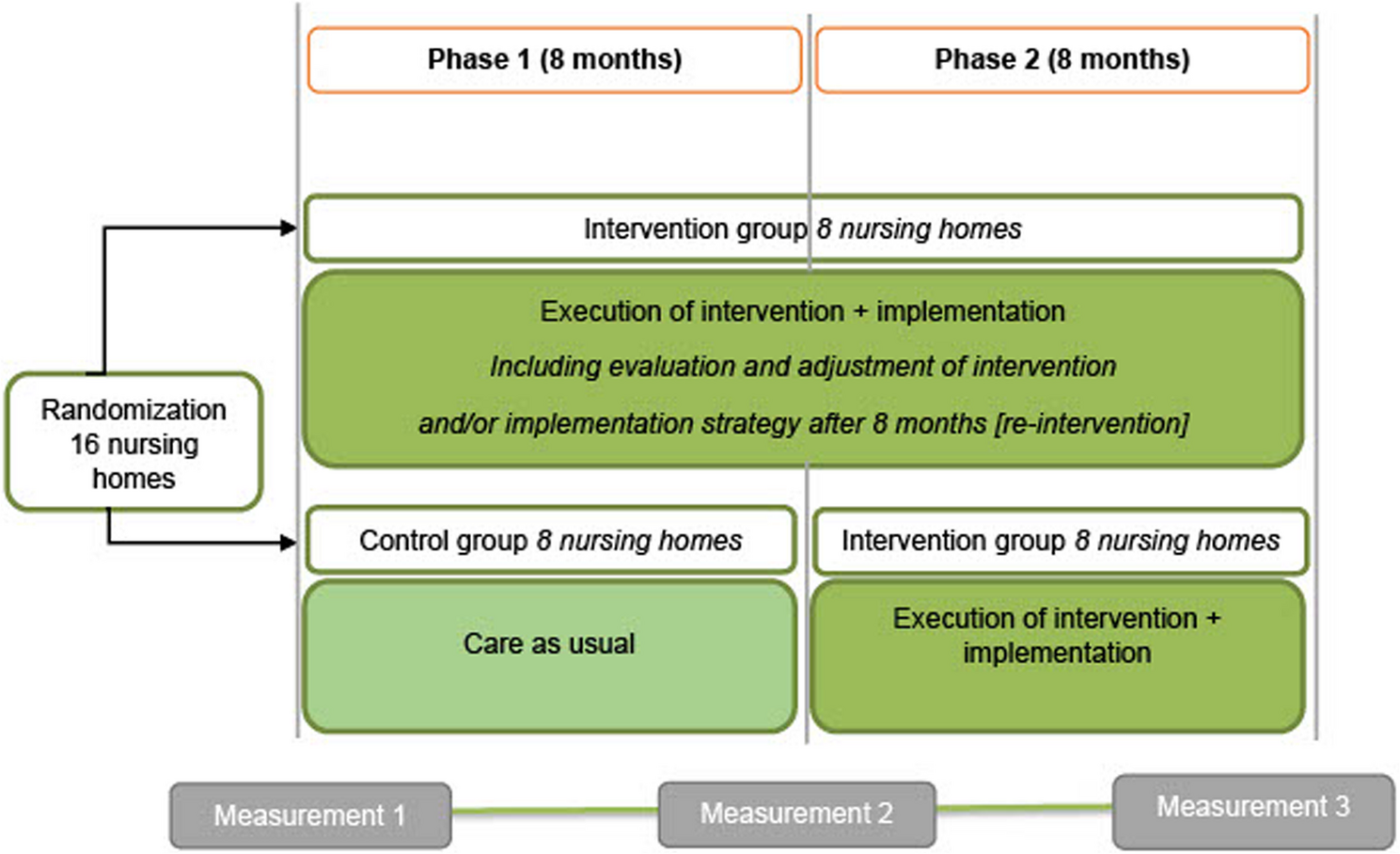

The stepped-wedge design [47] had an overall duration of 16 months and comprised two 8-month phases, with measurements taken at baseline, 8 months, and 16 months. Phase one started with 16 nursing homes randomized to either the RID intervention group or the control group (usual care). Phase two started after 8 months with the nursing homes in the control group crossing over to the RID intervention group and the other eight nursing homes continuing with the RID intervention (Fig. 1). An independent statistician performed computer-generated blinded randomization in fixed blocks: round 1 (6 homes; blocks, 2-2-2) and round 2 (10 homes; blocks, 4-2-4) [45].

The RID Study: A special case of a stepped-wedge design with one step, two phases and three measurements RID = reducing inappropriate psychotropic drug use

Setting and participants

In the Netherlands, nursing homes provide dementia care in special care units (DSCUs). An elderly care physician typically has responsibility for any medical treatment, working in close collaboration with a psychologist, nurse practitioner, and nursing staff with varying levels of education and responsibilities. Homes may also employ physical, occupational, and activity therapists to improve wellbeing, functioning, and quality of life [48, 49]. In 2015, The Dutch government implemented a major reform aiming for elderly persons to stay as long as possible in their own homes. Residential care homes, taking care of elderly persons with moderate levels of impairment, were shutting down. Consequently, the threshold for admission to a nursing home increased. Only persons with complex health care problems in need of 24-hour surveillance and multidisciplinary care are eligible for admission. As a result, residents often have a quite short length of stay and relatively high mortality rates. In this respect, Dutch nursing homes may be different as compared to nursing homes in other countries [48].

We recruited nursing homes online after attending a national kick-off conference with presentations and an information market. An intake telephone call was then scheduled to assess the suitability of each home for inclusion, with 16 homes included by their order of application. DSCUs delivering care for residents with Korsakoff syndrome, acquired brain injury and Down’s syndrome were excluded. Units delivering care for young-onset dementia were also excluded. No age restrictions were imposed within the DSCUs providing care for residents with dementia at an older age. Each nursing home participated with a few large-scale units or multiple small-scale units. Nursing home residents were eligible for participation if they had a diagnosis of dementia and a life expectancy of at least 3 months, as judged by a physician. All eligible residents were approached for participation, including newly admitted residents, after the study began. More information can be found in the study protocol [45].

RID intervention

A detailed description of the RID intervention can be found elsewhere [50]. The RID intervention involved forming a multidisciplinary project team with an internal project leader, a physician, a psychologist, and a nursing staff representative, together with a certified external coach to guide the cyclical process across four phases. Each intervention started with researchers executing a problem analysis on the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms and the appropriateness and percentage of current psychotropic drug use in their home (observation phase). The team then evaluated this tailored information and formulated specific goals under the guidance of the external coach (reflection phase), before operationalizing the goals into an action and implementation plan (planning phase). Finally, each nursing home implemented a set of interventions (action phase).

In some cases, there were differences between participating DSCUs within a nursing home, regarding the problem analysis or the potential solutions. Implementation was allowed to be tailored to a given DSCU, although in practice, most nursing homes developed and executed one action and implementation plan for all the participating DSCUs within their nursing home. The actions implemented by each nursing home varied based on their tailored problem analysis, but they generally targeted multidisciplinary and methodical working (including person-centered interventions), education and training, and adaptations to the living environment [50]. For the nursing homes that started in the RID intervention group in phase one, the measurement at 8 months was treated as an interim analysis that triggered the repetition of all four phases of the PAR cycle during the second phase of the trial (Fig. 1). Nursing homes that started in the control group in phase one provided care as usual for the first 8 months and entered an intervention cycle in phase two.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the primary outcome (inappropriateness of psychotropic drug use). To detect a reduction of 5 points (standard deviation 15) on the Appropriateness of Psychotropic Drug Use in Dementia (APID) index with a power of 0.80, a two-sided α value of 0.05, and an average of 25 residents per nursing home, we estimated the need for 16 clusters (nursing homes). Not taking clustering into account, we needed to include 284 residents who used psychotropic drugs. However, allowing for the multilevel design with two measurements after baseline, an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.1, a calculated design factor of 1.28, and a 10% cluster dropout, this increased to 364 residents. Given that an estimated 60% of residents with dementia are prescribed psychotropic drugs [17], we needed to include 607 residents (i.e., psychotropic drug users and non-users). We attempted to mitigate the expected 40% loss to follow-up by enrolling newly admitted residents throughout the study [45].

Outcomes and data collection

Data on age, sex, dementia diagnosis, length of stay in the current DSCU, and number of psychotropic drugs were collected from each participant’s medical record. Both outcomes (inappropriateness– and percentage of psychotropic drug use) were also extracted from the medical records of residents. A team of (junior) researchers with educational backgrounds in medicine, psychology and health sciences collected data. The research team together pilot tested scoring of inappropriate psychotropic drug use by means of the APID index. Psychotropic drug usage included prescriptions of antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and anti-dementia drugs. Anticonvulsants and antidementia drugs are listed as psychotropics drugs because they could have been prescribed to treat agitation in dementia and psychosis in Lewy Body dementia, respectively. Psychotropic drugs were grouped according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification [51]. We excluded psychotropic drugs used pro re nata. If residents died or relocated more than 2 months after the measurements at baseline or 8 months, we collected any recorded data on psychotropic drug use at the next measurement.

The primary outcome was the inappropriateness of psychotropic drug use, as measured with the APID index. The APID index was developed by an expert panel based on the items of the Medication Appropriateness Index. The index has been evaluated among DSCU residents in the Netherlands [52, 53]. The APID rates the appropriateness of psychotropic drug use for residents with neuropsychiatric symptoms and dementia. Therefore, psychotropic drugs given for dementia, sleeping disorders, or delirium are included in the scoring, but those given for other psychiatric disorders are excluded. The APID instrument contains seven domains: indication, evaluation, dosage, drug-drug interaction, drug-disease interaction, duplication, and therapy duration. Using data from medical records, each domain is scored 0, 1, or 2 to reflect “appropriate,” “marginally appropriate,” and “inappropriate” usage, respectively. During the development, an expert panel weighted the relative importance of each single domain on a scale from one to ten, resulting in different ranges per domain: indication (range 0-18.8), evaluation (range 0-19.2), dosage (range 0-13.4), drug-drug interactions (range 0-11.6), drug-disease interactions (range 0-13.2), duplication (range 0-14.4), and therapy duration (range 0-12.2). These single domains can be incorporated into a weighted sum score using mean weights. The APID sum score ranges from 0 (fully appropriate) to 102.8 (fully inappropriate) per rated psychotropic drug. Hence, lower scores indicate more appropriate psychotropic drug use [52]. The APID index applies different rules regarding the indication and evaluation domains for prescriptions that are started prior to nursing home admission and for prescriptions started at the DSCU of the nursing home. For example, for psychotropic drugs that are started at the current DSCU the normal rules apply: a (correct) indication needs to be found within two months after starting the psychotropic drug. To assess the indication of a psychotropic drug that is started before admission to the DSCU, a 6-month period is allowed. Moreover, the indication is still considered appropriate even if an indication is lacking or incorrect if the 6-month period has not yet expired. The rationale behind this, according to the expert panel that developed the APID index, was that the physician should be given enough time to set an indication and to evaluate the usage of psychotropic drugs that were prescribed prior to nursing home admission.

The secondary outcome was the percentage of psychotropic drug use, evaluated as a binary variable (i.e., yes/no).

Data about neuropsychiatric symptoms were collected using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home version (NPI-NH) [54]. A member of the nursing staff filled in paper versions of the questionnaire in the presence of a researcher. The NPI-NH assesses the frequency (score, 1–4), severity (score, 1–3), and caregiver distress (score, 0–5) for 12 psychiatric and behavioral symptoms. Item scores are generated by multiplying the frequency and severity [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], with possible scores ranging from 0 to 144, where a higher score indicates more frequent and severe neuropsychiatric symptoms [55].

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used to prepare the datasets and perform the descriptive statistics. Stata software, version 17.0, was used for all other analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of residents at baseline by treatment arm, with data included for newly recruited residents at 8- and 16-months’ follow-up.

For the primary outcome, data was used from the residents using psychotropic drugs, with single psychotropic drug prescriptions as the level of observation. We compared the inappropriateness of psychotropic drug use between the intervention and control groups using multilevel models to accommodate the hierarchical data structure. These models were used to adjust for the clustering of residents within nursing homes (random intercept at the nursing home level) and for the correlation of the repeated measures and multiple prescriptions within residents (random intercept at the resident level). The dependent variable was set as the change in APID index score between two consecutive measurements. The analysis was adjusted for the number of psychotropic drugs per resident, sex, baseline NPI-NH total score, length of stay in the DSCU at baseline (in months), and time in the study arm. Residents were evaluated in four groups: full duration, later enrollment, early drop out, and later enrollment with early drop out. Time and the interaction of time with treatment were included as fixed effects. The model compared changes in the APID index sum score between baseline and either 8- or 16 months. Multilevel models were fitted with the restricted maximum likelihood method, and effect estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values. Newly admitted residents were included at 8- and 16-month’s follow-up, but, considering that change scores were used for the primary outcome, data was only taken into account when residents were included in at least two measurements.

A different dataset and structure were used to evaluate the secondary outcome, percentage of psychotropic drug use. This dataset included all residents (psychotropic drug users and non-users) with observations at the resident level. Data of residents included at 8- and 16-month’s follow-up was taken into account. Psychotropic drug use between the control and intervention groups was compared by logistic generalized estimating equations (GEE), accounting for the clustering of repeated measurements within residents. GEE was used because it generates population average estimates that are preferable for intervention studies [56]. The model contained psychotropic drug use (yes/no) at 8 and 16 months as the dependent variables and assessed the main effect by group (intervention vs. control). We intended to correct for baseline NPI-NH sum score and baseline psychotropic drug use. Given the possibility of collinearity between these variables, they were added to the model one by one. Many residents were not included at the baseline measurement, which led to missing data; however, imputation was not feasible because the data concerned the period before admission. Two GEE models were ultimately executed: (1) analysis of all cases without correction for the NPI-NH sum score and psychotropic drug use at baseline, and (2) analysis of complete cases only, with subsequent correction for the NPI-NH sum score and psychotropic drug use at baseline. Adjustments were made for sex, length of DSCU stay (in months), and time in the study arm (full duration, later enrolment, early drop out, and later enrolment with early drop out; for all cases only). In addition to overall psychotropic drug usage, we performed post hoc analyses for psychotropic drug subgroups: antipsychotics, anxiolytics, antidepressants and hypnotics. We did not perform analyses for anticonvulsants and anti-dementia drugs separately, because of the small sample sizes within these groups. Several models were executed for each subgroup, in line with the analysis of overall usage. The models adjusted for confounders and containing all cases are considered the main models for both the pre-specified and post hoc analyses.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes that considered the results of the process evaluation by excluding nursing homes with tardy or low implementation (n = 4) [50].

There were some deviations from the study protocol [45], see Additional file 1.