by Riko Seibo

Tokyo, Japan (SPX) Nov 15, 2025

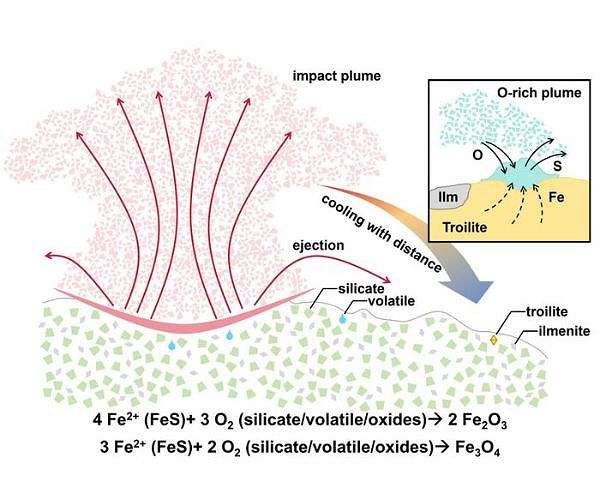

Researchers from the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGCAS), and Shandong University have identified, for the first time, crystalline hematite and maghemite…

by Riko Seibo

Tokyo, Japan (SPX) Nov 15, 2025

Researchers from the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGCAS), and Shandong University have identified, for the first time, crystalline hematite and maghemite…