In this study, we describe health-seeking behaviour, perceived financial impact and the mental health of TB survivors one year after the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings show that Governments’ response to COVID-19 affected healthcare-seeking behaviour, financial status and caused psychological distress.

In terms of financial impact our results show that during the COVID-19 pandemic and government restrictions, TB survivors suffered job losses and reduced working hours. Our results support other studies and reports in terms of the financial impact of COVID-19 on individuals in South Africa including TB survivors. For example, according to a report by the South African National Treasury, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the South African economy, with an estimated loss of 300 billion Rand in tax revenue for the 2020/2021 fiscal year alone [20]. Our results show that the financial impact felt during COVID-19 was as a result of job losses, reduced working hours and high cost of food. Loss of jobs highlighted in our study was reported in The Gambia. A report on the impact of COVID-19 on poverty in The Gambia showed that unemployment rates increased from 9.5% to 11.5% from 2019 to 2021, also that there was a reduction in economic activity since people’s incomes had decreased and the prices of goods increased [21]. Even in situations where there are no pandemics TB survivors are known to suffer job losses and income losses after TB treatment completion [6, 7, 22].

A third of patients reported a loss of capital (dissaving). Dissaving is a useful indicator of financial hardship [23] and is when individuals spend money beyond their available income. This may be accomplished by tapping into savings, selling assets or property or borrowing against future income. Self-employed people and small businesses were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This is similar to what was reported in a report on the Impact assessment of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small and medium sized enterprises in The Gambia. The report showed that the pandemic had an impact on the livelihoods of traders with 62% of micro, small and medium sized enterprises reporting that the pandemic led to a reduction in their earnings [6, 24]. Following an income shock, households typically reduce spending and assets, diversify income sources, and adjust household composition or location [25]. Half of the patients reported a change in household composition since the start of COVID-19.

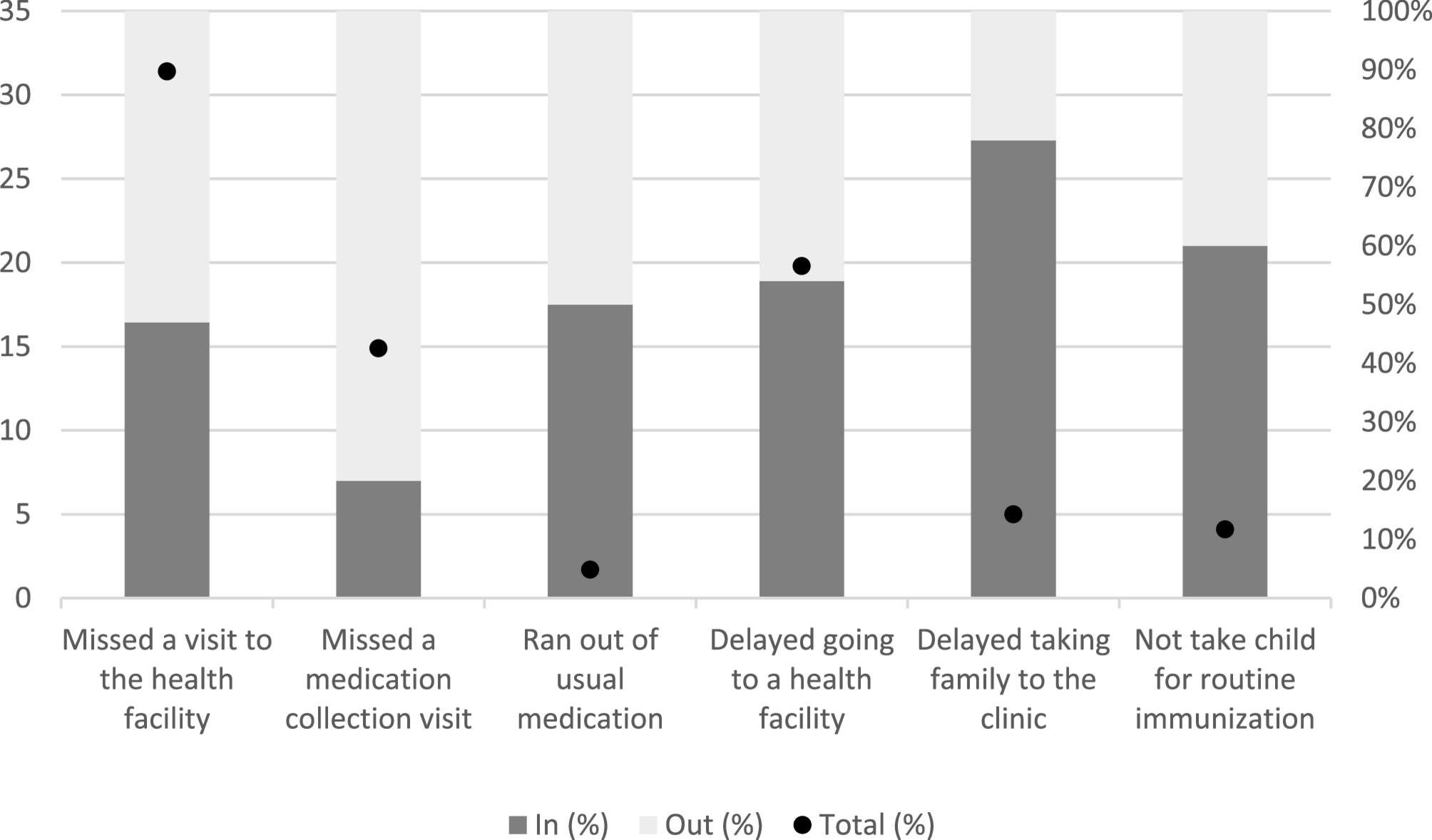

According to our findings, governments’ response to COVID-19 affected the healthcare-seeking behaviours of TB survivors with people missing scheduled visits and avoiding seeking care for other non-COVID-19 conditions. This was supported by other reports in the region. In South Africa, the Human Science Research Council reported that among people living with HIV, 13% did not have access to their medication during the COVID-19 lockdown [26]. In Mozambique, a study done on the effects of COVID-19 on child health services utilization and delivery reported a decrease in child consultations at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and persistent declines in monthly consultations [27]. In Ethiopia, about 39% of patients with chronic diseases were reported to have poor health-seeking behaviour [28]. Interestingly, missing a medication collection visit was predominantly experienced outside of the COVID-19 waves, possibly due to fear of COVID-19 transmission, stigma surrounding respiratory symptoms, financial losses, lack of passenger transportation, cost of transportation, and accessibility of healthcare workers [18].

Our findings show that TB survivors experienced notable distress. There are significant differences in psychological distress across countries. Mozambique appears to have better mental well-being, while The Gambia shows the highest burden. The findings may reflect underlying socio-economic, health, or contextual differences that should be explored further.

In all three countries, when there was a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases, there was a sharp decrease in TB survivors seeking care. Our findings echo similar trends reported by others; for example, in TB testing in South Africa, the social distancing measures implemented from 16th-27th March 2020 resulted in a decline in daily testing volumes compared to the preceding week [29]. During the time of South Africa’s level 5 lockdown implementation in late March 2020, or even a little earlier, a dramatic fall in ART initiations was observed in every province, possibly in response to the declaration of a state of disaster in the middle of March 2020 [30].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health guidelines, service updates, and COVID-19 information were primarily disseminated through digital platforms, including websites, social media. For those without access to smartphones, computers, or internet connectivity were often excluded from these communication channels, possibly leading to health seeking delay.

The association between HIV status, specifically being on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and experiencing a serious impact on health-seeking behaviour underscores the heightened vulnerability of individuals living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding underscores the importance of integrated healthcare services and targeted support for populations with pre-existing health conditions. Being seriously financially impacted during COVID-19 was associated with moderate or serious impact on health-seeking behaviour, highlighting the notion that poor financial status hinders the decision to use health services leading to poor care-seeking behaviour [31].

Additionally, the marginal association observed between lack of formal education and the serious impact of COVID-19 restrictions on health-seeking behaviour underscores the need for education and awareness campaigns tailored to vulnerable populations. Addressing barriers related to education can empower individuals to make informed decisions regarding their health, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of pandemics on healthcare access.

Our finding also highlights that males have poor seeking behaviour compared to females, this is consistent with literature [32,33,34]. A study in South Africa explored factors that contribute to men’s poor health seeking behaviour and found some of the factors to be fear of knowing own health status, consulting friends and masculinity beliefs [33]. There is need to recognize the challenges faced by men in health seeking behaviour and urgently address them.

We found an association between social changes (any report of affected relationships, increased psychological distress or anxiety or food or income insecurity) and experiencing a serious impact on health-seeking behaviour. This finding is similar to findings from a study done in South Africa which showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic relationships were impacted in three most common ways; communication and connection; strained relationships; and job and economic loss [35].

Implications

These findings highlight the importance of considering the broader socio-economic and healthcare implications of pandemic responses. Future pandemic preparedness efforts should prioritize strategies to mitigate the negative impact on healthcare-seeking behaviour, particularly among vulnerable populations, and address the underlying social determinants of health to build resilience and improve response effectiveness. National TB programmes should integrate contingency plans that ensure uninterrupted access to TB services during pandemics. This includes maintaining drug supply chains, decentralizing treatment delivery (e.g., community-based or digital adherence technologies), and designating TB services as essential healthcare that remains operational during lockdowns or public health restrictions. Policymakers should consider targeted interventions to support people affected with TB and other health conditions, especially in regions with higher vulnerability, by addressing financial hardships, ensuring continuity of care, and integrating mental health and psychosocial support services into pandemic response plans. Policymakers should embed financial support mechanisms such as transport vouchers, food parcels, and cash transfers into pandemic response frameworks. Pandemic preparedness plans must incorporate mental health and psychosocial services as a standard component of care for TB patients and other vulnerable groups. Community health workers and TB nurses should be trained to recognize psychological distress and refer patients for support, and tele-counseling services should be expanded to ensure access even during movement restrictions. In summary, addressing the complex interplay between socio-economic factors, healthcare access, and psychological well-being is crucial for enhancing pandemic preparedness, mitigating long-term impacts, and improving patient support during public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our findings may contribute to the body of evidence and data regarding the impact of COVID-19 on health-seeking behaviour. The findings would enable national TB treatment programmes to strengthen the capacity of primary health care facilities to improve their post-TB care to TB survivors.

Limitations

The findings in this study are limited by the lack of a control group since we only interviewed TB survivors. We only include TB Sequel study participants. Participant’s experienced trust, established relationships with study staff, and better experience (i.e., no queuing and receive a reimbursement etc.) so this may have influenced their health-seeking behaviour and the perceived financial or psycho-social impact of COVID-19. Not everyone is completing the COVID-19 questionnaire at the same point after treatment, which means that responses could be influenced by the time elapsed since treatment completion (and related follow-up visits) rather than by the COVID-19 restrictions themselves. In other words, the need for healthcare engagement might vary depending on the time since treatment ended, and may not be as significantly impacted by lockdown measures.

This study is a cross sectional study therefore; we cannot establish causality because it’s impossible to determine whether the exposure preceded the outcome. We used logistic regression model to estimate Odds Ratios (OR) which can over-estimate where the outcome is >10% and is not a rare event.

TB Sequel is an observational cohort study so some explanatory variables may not have been collected and the analysis could only include what data was collected through the COVID-19 questionnaire and the main cohort data. We only considered individuals who attended a TB Sequel follow-up visit from April to October 2021. We did not conduct interviews with those who returned outside of this timeframe, nor do we possess data on those who did not return at all. Additionally, we are uncertain if the psycho-socio-economic effects of COVID-19 influenced their health-seeking behaviour. For some of the TB Sequel participants who had COVID-19 before the interview, this may have in itself contributed to additional out-of-pocket expenses for testing and treatment of symptoms, contributing to the perceived financial impact of COVID-19.

Another limitation is recall bias; participants were asked to recall things that had happened a year or more before the interview date.