The age of borderless tech is ending.

For decades, global technology firms operated on the assumption that markets were open, supply chains integrated and politics a background variable.

Now, multinationals must navigate a landscape in which compliance with state authority outweighs cost-efficiency and scale.

What was once a question of strategy is now a matter of survival.

Nowhere is this shift more apparent than in the technology sector. US export controls, tariffs and investment restrictions – especially those targeting China – have redrawn the boundaries of market access, research and development (R&D), collaboration and supply chain design.

China, in turn, has tightened procurement standards and retaliated against firms deemed complicit in Washington’s containment agenda.

The result is a world where geopolitical sensitivities govern commercial viability.

The end of global arbitrage

The traditional model of multinational expansion – arbitraging labour, regulatory gaps and tax jurisdictions (in other words, finding the cheapest workforce, laxest red tape and most advantageous tax regime) – has unravelled under rising techno-nationalism.

For decades, tech multinationals thrived on a transnational division of labour: design and intellectual property in Silicon Valley or Eindhoven; high-volume manufacturing in Guangdong or Jiangsu; and increasingly, component production or final assembly in emerging sites like Thailand or Vietnam.

That model is now under siege.

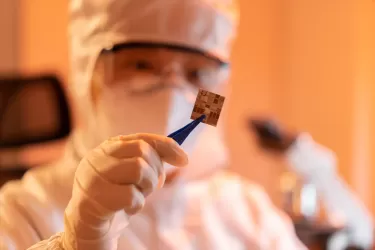

US tariffs under Section 301, far-reaching export controls on advanced semiconductors (including AI-optimised chips), and the restrictions embedded in the CHIPS and Science Act have raised transaction costs and introduced new political risks.

But more than that, they have signalled a normative shift. Global value chains are no longer governed solely by economic logic but by strategic imperatives around security and autonomy.

Researchers are seeing that geopolitical fragmentation is compelling firms to reconfigure supply chains around blocs of political alignment – friend-shoring, redundancy and regional clustering are rapidly replacing ‘just-in-time’ globalism.

Multinationals like Nvidia, ASML and Applied Materials are now being forced to decouple parts of their supply chains from China – even as they depend on Chinese demand for scale, margins and technological relevance.

These firms sit at the heart of critical infrastructure for AI, advanced semiconductors and industrial automation.

Yet US export controls increasingly limit what they can sell to Chinese clients.

At the same time, Beijing has begun issuing informal ‘window guidance’ to state entities to avoid procurement from firms like Intel and AMD – signalling a strategic shift away from foreign suppliers perceived as aligned with Washington’s containment strategy.

The contradiction is sharp: to lead globally in advanced tech still requires presence in China, but that very presence is now politically contingent.

Weaponised interdependence

The United States has not only constrained trade – it has repurposed global networks as tools of coercion.

As American political economists Professor Henry Farrell and Professor Abraham Newman argue, weaponised interdependence allows states to exert power over firms through their dominance of key chokepoints – finance, software, standards and intellectual property.

For tech multinationals, this has created new fault lines.

American giant, Nvidia, cannot export its most advanced graphics processing units (or GPUs) to Chinese customers, even via third countries.

ASML, a Dutch firm, is prohibited from selling extreme ultraviolet lithography systems – used for semi-conductor manufacturing – to China under US pressure.

These restrictions aren’t symbolic; they sever firms from the world’s second-largest market, undermining both revenue and the scale needed for frontier R&D.

Beijing, in response, is enforcing its own restrictions.

Foreign firms seen as aligned with US controls are being excluded from procurement by state-owned enterprises and government agencies.

The result is a fragmented commercial landscape where multinationals are no longer truly global – they are segmented, disciplined and increasingly defined by the geopolitical posture of their home country.

Strategic adaptation

But all is not lost. Tech multinationals still have room to manoeuvre – if they recalibrate.

A full decoupling is unlikely; what we are witnessing is selective disentanglement and strategic realignment.

First, firms can focus on China’s vast enterprise and small-to-medium enterprise sector, which remains more commercially driven and less bound by state procurement mandates.

These segments continue to demand high-end chips, automation systems and digital services – areas where foreign firms still hold a competitive edge.

Second, China remains a critical base for export-oriented manufacturing, particularly into Southeast Asia.

Intra-Asian trade has intensified in recent years, with deepening economic interdependence between China and ASEAN countries.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – the world’s largest free trade agreement – further integrates China into a broader Asia-Pacific production ecosystem.

For multinationals, this provides a pathway to retain operations in China while strategically reorienting toward third-party markets.

Third, firms can pivot toward new growth corridors – like Central Asia, the Middle East or Eastern Europe – where China’s Belt and Road Initiative is expanding infrastructure and digital connectivity.

These regions are increasingly important to second-order demand and can serve as hedges against US-China volatility.

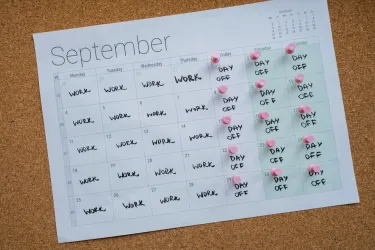

The key for these big companies is not withdrawal, but segmentation.

Commercial strategies must now reflect political geography. Product lines, partnerships and R&D pathways must be tailored to the realities of a divided world.

Navigating fragmentation

In this new era, the globally dominant, efficiency-maximising multinational may be a relic.

But a regionally embedded, politically agile and strategically selective tech firm is not only viable – it may define the next chapter of globalisation.

Innovation no longer happens in a vacuum. It unfolds within the constraints of geopolitical power.

The challenge for multinationals is not how to restore the old global order – but how to survive, adapt and lead within its fracture.