Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, the Soviet Union’s greatest composer – and a man whose relationship to that regime was complex and ambivalent – died on 9 August 1975. Fifty years on, few living musicians even in Russia can offer first-hand accounts of Shostakovich; fewer still in the West, thanks to the infrequency of the composer’s overseas visits and the political restrictions on his activities this side of the Iron Curtain.

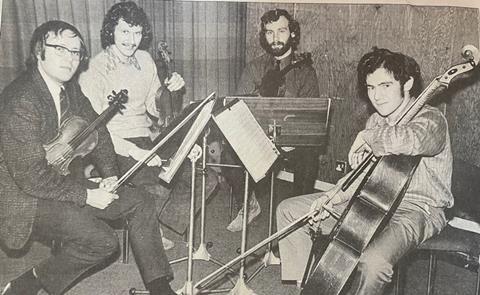

But for the four British musicians who made up the first incarnation of the Fitzwilliam Quartet, playing to Shostakovich was a ‘life-changing’ experience, in the words of cellist Ioan Davies. Violinist John Phillips, who enjoyed a distinguished legal career after leaving the quartet, describes meeting Shostakovich as ‘the two most memorable days of my entire professional life’; violist Alan George reflects that playing for the composer at such a young age gave him the confidence that he – and the quartet – ‘could do anything’.

While still in their early twenties, these musicians gained the extraordinary opportunity to give the first performances outside Russia of Shostakovich’s Thirteenth String Quartet, and the still more unexpected privilege of playing for the composer himself. It is obvious from my conversations earlier this week with three of the original quartet members how much the experience still means to them.

The Fitzwilliam Quartet began in autumn 1968 when Phillips overheard a fellow first-year violinist in the practice rooms at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge: though ‘slightly annoyed to find there was someone there better than me’, he suggested to the violinist that they should form a quartet, and Nicholas Dowding thus became the Fitzwilliams’ first leader. The pair were quickly joined by George, a King’s music scholar from Cornwall, and the Welsh Davies, who was at St John’s.

In George’s words, ‘we weren’t the best quartet in Cambridge, but we stuck at it’: they performed regularly in their colleges and for the University Music Club and spent their summers together learning new repertoire. From the outset, that repertoire included Shostakovich. Dowding, Phillips and George had been profoundly affected by playing the Tenth Symphony in the National Youth Orchestra, and Davies had discovered the Eighth Quartet by borrowing the score from a library in Llanelli, so the group responded positively to Phillips’s bold suggestion of programming that piece for their professional debut in 1969 at the Arts Festival in his home town of Sheffield.

Although the Eighth was performed quite often in Britain, the other eleven quartets then in existence were much less familiar. All were composed after the crisis of 1936, when Shostakovich’s opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, was notoriously castigated in Pravda as ‘muddle instead of music’. He turned increasingly to chamber music, perhaps in part to explore feelings too risky to express in the ‘public’ forms of symphony and opera.

Fired by their success with the Eighth, the Fitzwilliam players explored several of the other quartets during their time in Cambridge. Perhaps surprisingly, the sheet music was readily available in the UK: some quartets were published by Boosey and Hawkes, others by Musica Rara, no.3 by the Moscow-based State Music Publishers.

It was only in 1971, however, as the quartet members were about to graduate, that George discovered the existence of a Thirteenth Quartet. He came across an LP by chance in the Anglo-Russian music shop that operated at that time in west London: when he listened to its single 20-minute movement, he found it ‘mind-blowing … quite unlike any of the previous quartets’. Shostakovich had composed the Thirteenth the previous summer during a period of treatment at a hospital in the Urals; the Beethoven Quartet premiered it in Moscow in December 1970.

When violist Alan George listened to the Thirteenth Quartet he found it ‘mind-blowing … quite unlike any of the previous quartets’

As a violist, George must have been particularly struck by the work’s dedication to Vadim Borisovsky, the Beethoven Quartet’s original viola player, and the unusual prominence of the viola part, which begins with an unaccompanied complete twelve-tone row, and ends with a keening, stratospheric solo. But he could not check his impressions against the score: the sheet music was not available outside Russia.

Immediately after graduating, the Fitzwilliam Quartet took up a residency at the University of York. The University itself was less than a decade old, and the new department created by Wilfred Mellers, David Blake and Peter Aston was dynamic and focused on new music; the residency, with ample time allocated for rehearsal and learning new repertoire and concert opportunities across the region, was the sort of opportunity of which young British quartets today can only dream.

In summer 1972, George became aware that Shostakovich was visiting the Aldeburgh Festival, so he wrote to him care of the Soviet Embassy in London to ask for parts for the Thirteenth Quartet and permission to perform the work. Shostakovich replied immediately, not only granting George’s requests but also expressing the hope that he might be able to hear the Fitzwilliam Quartet perform the work in person.

Shostakovich’s return to Britain that November for the UK premiere of his Fifteenth Symphony had already been announced, so the quartet planned two performances of the new quartet in Harrogate on 11 November and at the Jack Lyons Concert Hall on the York campus five days later. However, it was only a few days before the Harrogate performance that Shostakovich’s availability for the York concert was confirmed.

George was deputed to meet him, his wife Irina and their interpreter at York station, having borrowed his father’s Ford Cortina for the occasion: he was surprised to encounter ‘a much bigger man than I had expected, yet physically very frail on account of his poor health.’ Even in an era before social media, and notwithstanding Shostakovich’s determination to avoid unnecessary publicity, York University’s press office disseminated the news of his arrival far and wide.

Extra capacity at the concert was created by allowing audience members to sit around the quartet on the platform: some so close, Phillips recalls, that they could read the music from the players’ stands. Clearly anxious throughout the performance – listeners behind him noticed him jittering – Shostakovich was visibly overwhelmed by the warmth of the audience’s response and the length of their ovation as he linked hands with the players on stage.

Shostakovich was visibly overwhelmed by the warmth of the audience’s response as he linked hands with the players on stage

His reaction is testimony to the humility and generosity that all the players remember as dominant characteristics. Earlier that afternoon, conscious of the quartet’s nerves – ‘I don’t know how I got the bow on the string!’ says Phillips – Shostakovich encouraged them to play the piece through to him in private. His eyesight was so poor that he held the score almost against his trademark spectacles before peering over it to make occasional comments through his interpreter. Any mild dissatisfaction was directed only at himself, for having not got his dynamic markings quite right: he adjusted some pizzicatos towards the end of the piece from piano to forte.

During that session and the unscheduled playthrough of movements from his other quartets he invited them to give in his room in York’s Station Hotel the morning after the concert, Shostakovich did not ‘coach’ the quartet or try to change the way they played: he simply told them that ‘you play very beautifully and it will be wonderful’, in Davies’ recollection. They might have wondered at the time whether the composer was making allowances for their youth and inexperience, but his admiration was genuine.

Shostakovich did not ‘coach’ the quartet: he simply told them that ‘you play very beautifully and it will be wonderful’

Many years later, George discovered that Shostakovich described the Fitzwilliams to Benjamin Britten as his preferred interpreters of his string quartets, and encouraged him to book them to perform the Fifteenth Quartet in Aldeburgh. Sadly, both Shostakovich and Britten died before this invitation could be issued.

Following his visit to York, Shostakovich maintained a correspondence with the Fitzwilliam Quartet for the remainder of his life, entrusting them with the Western premieres of his final two quartets (‘I shall be very glad if this work interests you and you include it in your repertoire’) and inviting them to play for him in Moscow. That visit was scheduled for September 1975, but Shostakovich’s death from heart failure at only 68 prevented it from happening – and cut short the composer’s plan to complete a cycle of string quartets in each of the 24 major and minor keys.

Nonetheless, Shostakovich remained central to the Fitzwilliam Quartet’s repertoire. With new violinists Christopher Rowland and Jonathan Sparey, they recorded a cycle for Decca that was the first to include all 15 quartets, and remains one of the most highly regarded interpretations on disc. The quartet was invited to perform Shostakovich all around the world, including in Russia, and as all three musicians I spoke to agreed, it was usually their Shostakovich that audience members wanted to discuss when speaking to them after concerts.

Davies left the quartet in the 1980s, subsequently playing in two piano trios (the Debussy and the Bohemia), but he continued to explore the Shostakovich quartets in his capacity as a teacher at the Wells Cathedral and Menuhin Schools. His view of them has changed – he is now much more aware of their intellectual rigour and architectural strength than he was when he first played them – but he remains struck by their immediacy of communication: ‘the music cried out at us, and all the young quartets I’ve taught have been drawn into it immediately.’

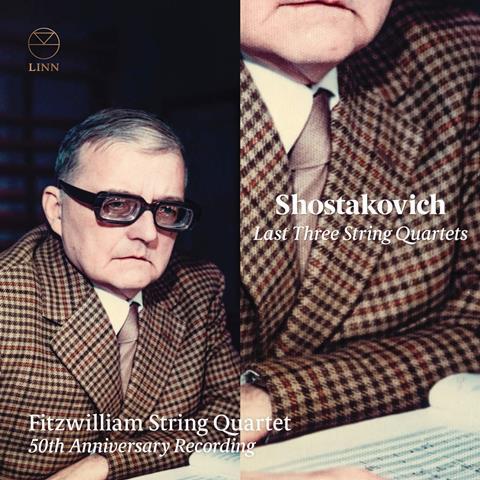

George, meanwhile, remained as the Fitzwilliam’s violist until late last year, his 56 years with the group making him the longest-serving quartet player in British musical history. One of his final recordings was a disc for Linn of Shostakovich’s final three quartets, made with violinists Lucy Russell and Marcus Barcham Stevens and cellist Sally Pendlebury, and praised by Gramophone as ‘performances born of honesty and of love: a deeply moving document’.

It is obvious from speaking to George that his emotional connection with Shostakovich’s music is stronger than ever. During his 24 hours in York, Shostakovich overcame barriers of language, politics and illness to establish a bond with the young Fitzwilliam players that nurtured their entire careers. Fifty years after his death, his quartets continue to speak to audiences with a directness that few works can match.

Michael Downes is director of music at the University of St Andrews. His recent book, Story of the Century: Wagner and the Creation of The Ring, is published by Faber.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

In the second volume of The Strad’s Masterclass series, soloists including James Ehnes, Jennifer Koh, Philippe Graffin, Daniel Hope and Arabella Steinbacher give their thoughts on some of the greatest works in the string repertoire. Each has annotated the sheet music with their own bowings, fingerings and comments.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.