Marshall Bruce Mathers III is a man of many names. But no matter what you call him — Marshall, Slim Shady, or the name by which he’s best-known, Eminem — he’s undoubtedly a household name. In fact, he’s the top-selling hip-hop artist of all time, and in turn, one of the most popular artists of all time, in any genre.

He’s no slouch when it comes to awards, either. Eminem has 15 GRAMMYs, and a total of 47 nominations. His latest album, The Death Of Slim Shady (Coup De Grâce), earned three nods at the 2025 GRAMMYs, including his eighth for Best Rap Album — a Category he’s won six times.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of one of those GRAMMY-winning albums, The Marshall Mathers LP. After breaking through with his second set, 1999’s The Slim Shady LP, Eminem’s third album put the rapper into the dead center of early-2000s media and discourse. During that era, Eminem inspired protests, sold a now-unthinkable amount of albums, and inspired seemingly endless amounts of cultural criticism.

The Marshall Mathers LP also saw Eminem reacting to the expectations brought on by the massive success of The Slim Shady LP, beginning a chain of albums that react to the previous album that continues to this day.

Em’s 12 studio albums are just one component of his sprawling discography — which, along with several deluxe or extended versions of his LPs, include two separate greatest hits collections, mixtapes, collaborative and group projects, and movie soundtracks. And that’s not to mention guest features, unreleased tracks and other rarities.

There’s much more to Eminem than what many consider his classic period, which started with The Slim Shady LP and ended right before the release of his fourth album, Encore, in November 2004. But it is that season — where a white rapper from Detroit teamed up with Dr. Dre and rocketed to the peak of popular culture — that is at the center of the rapper’s discography and persona, and that he has in some ways been reckoning with since.

The best way to understand Eminem’s catalog is to break it down into several eras: his pre-fame output, where he was not yet fully artistically formed; the aforementioned classic period; the fall and subsequent rise that followed; a look back at his classic period, but with mature insights and fresh eyes; and, over the past few years, a reaction to the changed world around him.

Now, dig into each one of these eras, and how they all contributed to making Eminem one of rap’s greats.

The Pre-Fame Period (1996-1998)

Eminem’s first album, 1996’s Infinite, is a project he still seems slightly embarrassed by. It is, notably, not available anywhere online (at least not legally), and only the title track can be found on streaming services.

But it is worth hearing in order to understand Em’s whole story. It was recorded before he came up with the Slim Shady persona, and sounds like what it is: the earnest work of a talented mid-’90s underground rapper with an AZ obsession and a chip on his shoulder.

The dense rhyming that would characterize his mature work is there, as are hints of the troublemaker personality that would soon take over the world. All of that is mixed in with the odd cringe-worthy punchline (“I’ll run your brain around the block to jog your f—ing memory”) and resentment towards local radio stations for ignoring him — stations that, only a few short years later, wouldn’t stop playing his records.

That project is followed by the debut of his Slim Shady alter ego on the appropriately-named Slim Shady EP. This is where Em first finds his footing.

Slim Shady is the device Em used to say things you’re not supposed to say (one song begins: “Slim Shady, brain-dead like Jim Brady“), while providing a complicated artistic and philosophic out. The character gave Em permission to be extreme, and also room to claw back some of what he was saying, and question whether he really meant it.

The intro of the Slim Shady EP goes into this head-on, featuring tropes Em would use throughout his career. The demonic-sounding Shady tells him, “You’re nothing without me,” in a skit that could appear verbatim on his most recent project, The Death of Slim Shady.

Musically, Eminem has discovered that evil sells. Letting his most deranged thoughts loose makes him sound far more energized than on Infinite, and already, even before meeting with Dre, he has a unique voice and style.

One other project happened during this era that’s worth mentioning: a single with Royce Da 5’9″, “Nuttin’ to Do”/”Scary Movies,” which they released in 1998 under the group name Bad Meets Evil. It is a stellar piece of work, and even at that early stage Shady and Royce have a notable chemistry — one it would take them over a decade to fully explore.

The Classic Era (1999- Early 2004)

This was the time when Em could not miss. Pretty much everything he put out during this period was both artistically and commercially successful. Even seemingly throwaway efforts like his appearances on DJ Green Lantern’s Invasion mixtapes (three volumes of which were released between 2002-2004) were both memorable and newsworthy.

All of this began with Em’s discovery by Dr. Dre and the subsequent album The Slim Shady LP. Along with its influence on hip-hop, this album put its maker at the white-hot (pun intended) center of popular culture. Everything Eminem did or said got a reaction, which in turn inspired him to act out, which inspired more outrage. It was a cycle that ultimately led to burnout (more on that later), but for a few years it created something close to magic.

Read More: 4 Reasons Why Eminem’s ‘The Slim Shady LP’ Is One Of The Most Influential Rap Records

The Marshall Mathers LP showed Em at his provocateur best, playing in the sandbox of his newfound stardom and the outrage it inspired. The record has, as of this writing, sold over 11 million copies in the US alone, which should give you some idea of its astronomical impact. Eminem was reckoning with the fact that he moved from overlooked and ignored to multi platinum seemingly overnight — and he didn’t seem to be having an easy time of it. All of his grievances with fans, family and pretty much anything else he could think of were given the largest canvas imaginable.

Its follow-up, 2002’s The Eminem Show, was just as provocative, but had a wider focus. Slim Shady’s name was now being spoken in the halls of power, and he had some thoughts about that (and about America’s post-9/11 terrorism obsession) — as well as some jokes about then-VP Dick Cheney’s heart problems.

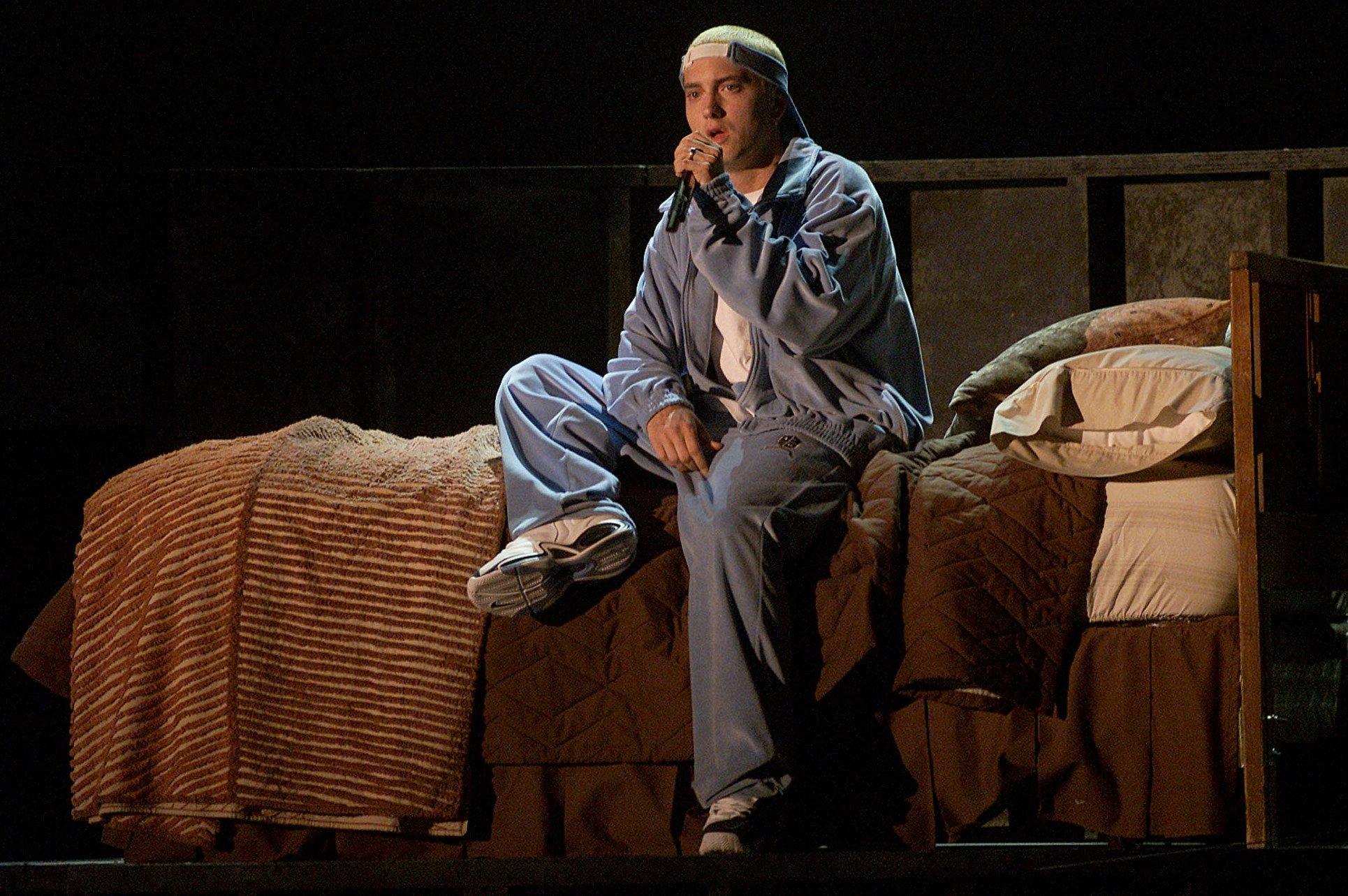

It wasn’t just the music that made this season so pivotal for Eminem’s career, either. He also starred in 8 Mile, a sort of fictionalized version of his battle rapping come-up, which proved that he was a big enough star that he could be at the center of a massively successful and compelling film. Naturally, he contributed a few songs to the film’s soundtrack, including the one that arguably solidified him as a global superstar: the chart-topping and GRAMMY- and Oscar-winning “Lose Yourself.”

He also, alongside Dre, discovered and signed 50 Cent, and produced and rapped on Fif’s monster 2003 debut, Get Rich or Die Tryin’. There were other major features during this period as well: virtuosic raps on songs by Missy Elliott, Jay-Z, Xzibit, and more. He even appeared on one of the very few worthwhile posthumous Notorious B.I.G. songs, “Dead Wrong.”

In addition, he somehow managed to find time during this period to release two albums from his group D12, both of which went platinum.

The Fall & Rise (Late 2004-2010)

Eminem himself summed up this period the best. “Them last two albums didn’t count,” he rapped on Recovery‘s “Talkin’ 2 Myself.” “Encore I was on drugs, Relapse I was flushing ’em out.”

The rise to megastardom began to take its toll. Em became trapped by the demands of celebrity, and by his own drug use. And it began to show in his work.

Encore contains a number of extremely juvenile songs with titles like “Ass Like That” and “Big Weenie” that would have been better left on the cutting room floor. There are also several tracks that simply retread concepts he had already done on his previous albums (“Mockingbird” is, for example, essentially “Hailie’s Song” redux).

That said, there are also occasional great moments: a mature look at the costs of rap beef (“Like Toy Soldiers”), and a glance back at his childhood that, in its seriousness and thoughtfulness, avoids the exaggerated, comic tall tales of his first album (“Yellow Brick Road”). The deluxe version of Encore contains several of his best songs of this era, “We As Americans” and “Love You More,” which were inexplicably left off the album proper.

Following Encore, fans would have to wait over four years for Eminem’s next release — and the result, Relapse, was a divisive record. Many heard it as a largely sub-par collection of serial killer stories, celebrity insults, pill addiction stories, and bad accents (the last of which he would apologize for later). But it was produced almost in its entirety by Dr. Dre, which has won it no shortage of fans over the years. And those same serial killer tales would become influential on a new generation; it is, notably, an album that Tyler, the Creator has repeatedly and publicly championed.

Recovery marked, well, Eminem’s recovery. It also set the template for a sound and a style he would use in future years. Sound-wise, there’s a heavy rock and roll influence: drums, guitars and organ that wouldn’t sound out of place on a classic rock station (not for nothing, Black Sabbath is sampled on “Changes”). Stylistically, he adds heavy amounts of puns to his repertoire for the first time, a device to which he would return again and again.

Read More: GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Eminem Show Love To Detroit And Rihanna During His Best Rap Album Win In 2011

The project aimed for hits, and it succeeded. Biggest of all, of course, was “Love the Way You Lie,” a ballad with Rihanna on the hook that was No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for seven weeks. This is yet another formula that Em would return to, as we shall see.

The Reflective Season (2011-2017)

By the time the 2010s began, Eminem began to acknowledge his past. Two projects in a row, Hell: The Sequel and the suitably-named Marshall Mathers LP 2, looked back at different aspects of his career.

The former of these found him re-teaming with Royce Da 5’9″ as Bad Meets Evil, this time for an EP-length project. The pairing hadn’t lost a step since the late ’90s, when they joined up for a fantastic single and a Slim Shady LP collaboration. Here, Em is less focused on his own story and mythology, and more concerned with simply rapping. He sounds happier and more free, more interested in wordplay than narrative.

Even his by-now-long running ultraviolent worldview is more palatable in tandem with Royce. It also sounds good to have Eminem rapping with someone else (his own records are notably short on guest verses). Hell: The Sequel is largely not thought of as a high point of Em’s discography, perhaps because it wasn’t released under his name. But in this writer’s estimation, it’s his best project outside of the classic period.

The sequel to the Marshall Mathers LP also looks back, but in a different way. Em is thinking about the people affected by the often-scattershot insults he hurled at the height of his fame, and treating at least some of them with nuance and empathy — including the frequent villain of many of his early tracks, his mother.

Sonically, the rock-influenced material is still there. And so is the Rihanna duet, repeated on “Monster.” There is also perhaps the best-known and showiest example of Em’s virtuoso rapping, “Rap God.”

This idea of legacy — the album literally has a song by that title — continues on 2017’s Revival. He’s concerned with how hard it is to live up to the expectations set by his own past work. He also continues to look back on his early years, but this time with a clear-eyed view of how it affected his daughter, which he looks at on “Castle.”

One other part of this record is a response to modern rap. Em has heard Migos and their then-ubiquitous triplet flow, and he’s got some things to say about it. That will come to a head shortly.

The Response Years (2018-Present)

Revival did not have a great critical or popular reception, which did not sit well with Eminem. Within eight months, he released Kamikaze, a record that was largely about that poor response to Revival. It is shorter and more focused than pretty much any other solo album he’s ever released.

It’s also perhaps the most bitter, which is no small feat. He was angry at the current state of rap and the media that covers it. The only relief comes with the song “Stepping Stone,” in which he examines his culpability in the collapse of his group D12.

That same cycle of an album responding to the previous album’s reviews continued on Music to be Murdered By, which literally begins with the couplet, “They said last album I sounded bitter/ Nah, I sound like a spitter.” He even responded to specific reviews, with this 2.5 star Rolling Stone review of Kamikaze a particular target of ire. He seemed frustrated that neither the seriousness of Revival nor the lashing out of Kamikaze got the acclaim he felt they deserved.

That said, MTBMB does have some standout tracks. There’s the moving “Leaving Heaven,” where Em responds to his father’s death in 2019. And there’s “Darkness,” which reimages the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting. Plus there’s “Yah Yah,” an excellent collaborative display of rapping with Black Thought and, yet again, Royce.

Em’s most recent project, The Death of Slim Shady, is also a reactionary album. But this time, it’s not a response to the reception of a previous album — instead, it’s a reaction to a changed social climate.

Eminem (or, more properly, his never-quite-buried alter ego) sounds like your angry uncle at Thanksgiving, or a “South Park” rerun. Gen Z, pronouns, the “PC police,” opposition to fatphobia — all of these come under fire. One of the songs, “Brand New Dance,” appears to be a slightly reworked 20-year-old leftover, which explains the track’s Christopher Reeve jokes.

The album openly deals with the same question that plagued Slim Shady EP‘s opening: is the bottle-blonde enfant terrible Slim Shady all that Marshall Mathers has to offer the world? He doesn’t appear to have come up with an answer yet. But the struggle to figure that out has led to a quarter-century of frequently compelling music, with the promise of a lot more to come.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos