Syntho has been quietly building a name for itself in electronic-music production circles with its service providing courses in mixing, mastering, sound design and arrangement.

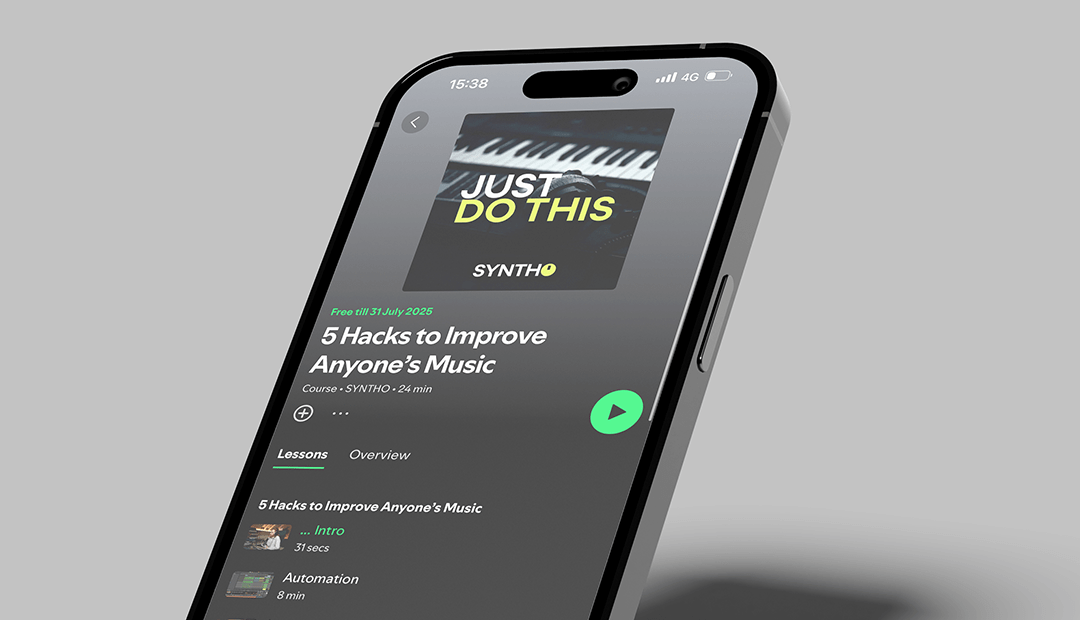

Now the UK-based startup, founded by musician Josh Baker, is taking some of those courses to an even bigger platform: Spotify. The ‘bite-sized’ lessons are part of the streaming service’s ‘Courses’ hub in the UK, which launched in March 2024.

Syntho is the second dedicated music-edtech provider for the hub, following PlayVirtuoso (since rebranded as Whatclass), although another of the partners – BBC Maestro – has some music courses alongside other topics.

A curated selection of Syntho courses – described by CEO Hazel Savage as “a highlight reel” of its full archive – can be accessed by Spotify Premium listeners as part of their subscription, for no extra cost.

“Spotify already have 15 million UK subscribers. Literally, a better go-to-market plan could not have landed in my lap!” Savage told Music Ally ahead of the launch. “Being able to put our content in front of that volume of people is incredible.”

Savage joined Syntho as CEO in February this year, but has a long history in music-tech that includes roles at Shazam, Pandora and BandLab before founding AI-metadata startup Musiio in 2018, then selling it to SoundCloud four years later.

She spent nearly three years as SoundCloud’s VP of music intelligence while also angel investing in startups including AudioShake, un:hurd Music, Masterchannel, Flossy and AI|Coustics, before taking the Syntho job.

“This is a company that did $700k in revenue last year, yet a lot of people haven’t heard of them. Anything that puts us more in the public spotlight is exciting,” said Savage.

“We will be able to bring people back from Spotify into the Syntho ecosystem as well. They’re very non-restrictive: the Syntho brand and the clickback to our website will be there. They’re not trying to gatekeep the content, so it works well for us.”

While the terms of the agreement are confidential, Savage said that the Spotify deal does generate revenue for Syntho – it’s not pure promotion – nor does it rely on the startup charging Spotify users to watch the courses.

“We already have 700 videos of paywalled content on Syntho, so I didn’t feel the need to paywall it on another platform. For me it’s a shop window,” she said.

On its site, Syntho charges £69.99 a month for an all-you-can-eat subscription, although the price falls to £43 a month and $33.33 a month for people who pay quarterly or annually respectively.

The courses are presented by working artists and producers, with Baker joined by Liquid Earth, Sweely, Alisha and a growing number of other musicians on its roster.

“The majority of Syntho users on our platform are on web. We must be the only music-tech company who are not mobile-first!” said Savage.

“If you’re sitting down to do Ableton or music production, you’re going to be at a desktop or a laptop, and probably multi-screening with two monitors. We do have iOS and Android apps, but we massively skew towards web. Spotify massively skews towards mobile, so it’s a complementary platform for that reason too.”

Savage thinks Syntho is part of a tech trend that isn’t being talked about much in public yet: of investors starting to move away from investments in AI startups in favour of “things that cannot be replicated by AI, which they see as a safer bet in retaining value”.

This may sound counterintuitive at a time of fears in all sorts of industries that AI is coming for people’s jobs. But as Savage points out, AI is also commoditising itself to some degree. When she started Musiio, building proprietary AI models was hard work. Now, with open-source and off-the-shelf models “there is not so much core IP around AI that’s investable”.

“Investors are putting a thesis around ‘how do we shore up our investments so that they’re profitable in the long run?’ I see this in other music verticals too. What are the hyper-specific, hyper-personalised, cannot-be-replicated [by AI] elements of our industry?” she explained.

“You can fake some things with a chatbot, but the minute people figure it out or it falls over, it’s worth less than nothing. You could type into ChatGPT ‘How do I use Ableton?’ and it will churn out a lot of text. But is it accurate? Will it really help you?”

“Or you can learn from someone like Josh Baker who’s doing a million streams a month on Spotify. That experienced, authoritative voice is what’s valuable… VCs are starting to spend their money in stuff that’s very specifically not AI, and not replicable. And investors are always two years ahead of where everyone else is…”

That’s not to say that Syntho is a not-AI company. Savage said that it’s looking for sensible ways to use AI technologies in its business: for example dubbing its courses into other languages. And as AI finds its way into more electronic musicians’ workflows, Syntho may well provide some courses about that.

Savage has followed the recent news of GenAI music firm Suno’s acquisition of browser-based DAW WavTool with interest – “So they made creation as easy as possible, and now they’re going to make it harder again?” – but thinks there’s a question that isn’t being asked loudly enough about Suno, Udio and their peers.

“The court cases are so huge, the raises of 100-mil plus are so big, we’ve never actually addressed the real question with Suno and Udio: is there any actual traction? Who is using those platforms,” she said. “Would anyone pay for this, and if so, are they actually going to use it?”

However, Savage’s priority is building more traction for Syntho, and plotting a careful course for its expansion both geographically and in terms of the content it offers.

“As CEO I’m looking at what does this ecosystem look like in 12-24 months. Is it a white-labelled Syntho? What does it look like if we want to roll out D’n’B (drum’n’bass) and techno? I’m looking at all of this,” she said. Over-expansion will be avoided: for example rushing to move beyond electronic music at too breakneck a pace.

“I’ve seen a lot of other music-tech platforms. If you try to do too much too quickly, what you are and what you do becomes confusing. You can throw in 20 features and suddenly people are like: ‘I don’t know what any of this is’,” she said.

“You see so many platforms do this and that. Now they’re a distributor. Now they do mastering. Now they’re also a label. Jesus, what IS the product?!” continued Savage.

“As much as I’d love to grow Syntho at lightning speed and become the biggest platform and branch out into all the genres, I want to do it in a way where we never lose the core of who we are, and who our community is. How do I grow this without losing what was good about it in the first place?”

Syntho is not actively raising funding right now, although Savage is “always open to conversations”. Her experience with Musiio, which raised $2m over its lifetime, taught her that there is a value in only raising money when you need it – and not raising more than you need to.

“There are some companies out there who’ve raised so much money, an exit is almost impossible. Recorded music is a $29.6bn market globally. It’s small compared to pharma or finance, and in an industry this size your chances of a billion-dollar exit are slim,” she said.

“Companies who’ve raised $10m or $20m need an exit of $100m to make anything they do worthwhile, and. the number of exits out there at that scale is very small. You either do it the Musiio way, and raise a little bit and sell at a good price, or you go full Kobalt and you’re a $1.2bn exit. There’s very little happening in that space in between.”

“Don’t get me wrong: I’m a big believer in this industry. I’ve personally invested in nine companies, all in music-tech. But you can really screw yourself over if you raise too heavily. You price yourself out of the market.”