Neanderthals in central Germany 125,000 years ago employed an advanced method of food preparation, according to a recent study: systematically stripping fat from the bones of large animals using water and heat. The practice, uncovered at the Neumark-Nord 2 archaeological site, shows that Neanderthals had a much more advanced conception of nutrition, planning, and resource management than previously believed.

The research, published in Science Advances, was conducted by international researchers from MONREPOS (Leibniz Centre for Archaeology), Leiden University in the Netherlands, and the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt. The study indicates that Neanderthals, in addition to smashing bones to access the marrow—a behavior shared by their earliest African ancestors—also crushed them into fragments and boiled them to obtain bone grease, a nutrient-rich resource.

“This was intensive, organized, and strategic,” said Dr. Lutz Kindler, the study’s lead author. “Neanderthals were clearly managing resources with caution—planning hunts, transporting carcasses, and rendering fat in a task-specific area. They understood both the nutritional value of fat and how to access it efficiently.”

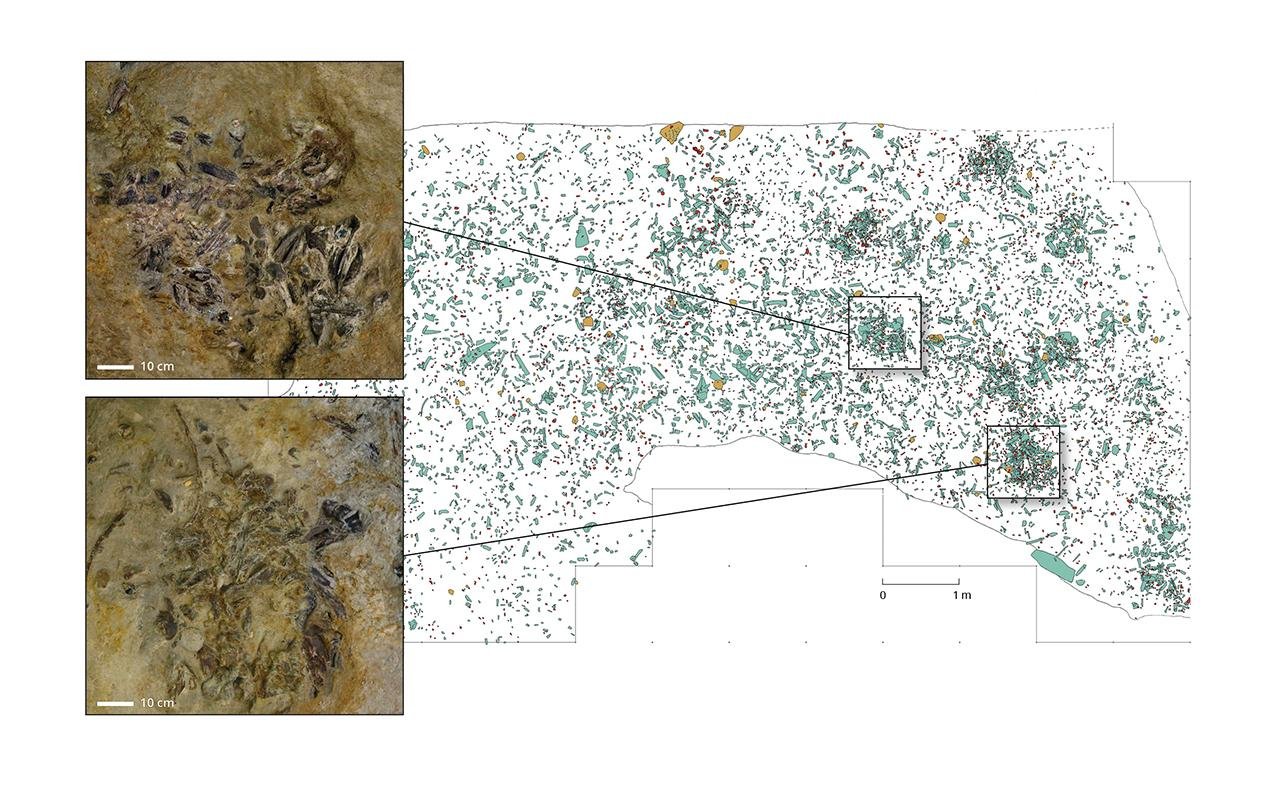

At least 172 large mammals, such as deer, horses, and aurochs, were butchered here. The production of bone grease, which required huge quantities of bone to be worthwhile, was previously considered to be something limited to Upper Paleolithic modern humans. This find pushes back the timeline by thousands of years and represents a fundamental shift in our knowledge of Neanderthal diet and adaptation.

The Neumark-Nord complex, discovered in the 1980s by archaeologist Dietrich Mania, is a full interglacial ecosystem. Excavations from 2004 to 2009 revealed several zones with various Neanderthal activities: deer hunting and light butchering in one, straight-tusked elephant processing in another, and fat removal in a third, specialized area. Remarkably, cut-marked remains of 76 rhinos and 40 elephants were also discovered at nearby sites like Taubach.

“What makes Neumark-Nord so exceptional is the preservation of an entire landscape, not just a single site,” said Leiden University’s Prof. Wil Roebroeks. “We are seeing a range of Neanderthal behaviors within the same landscape.”

The activities of the Neanderthals at Neumark-Nord not only demonstrate high sophistication but were also likely to have long-term environmental impacts. Prof. Roebroeks warned that their mass hunting of slow-reproducing species undoubtedly left a significant impact on fauna in the region during the Last Interglacial period.

The finds depict the Neanderthals as more capable and more intelligent than the stereotype of the brutish caveman. The “fat factory” at Neumark-Nord reveals a species that could plan for the future, manage its environment, and maximize nutrition in resource-poor environments.

More information: LEIZA