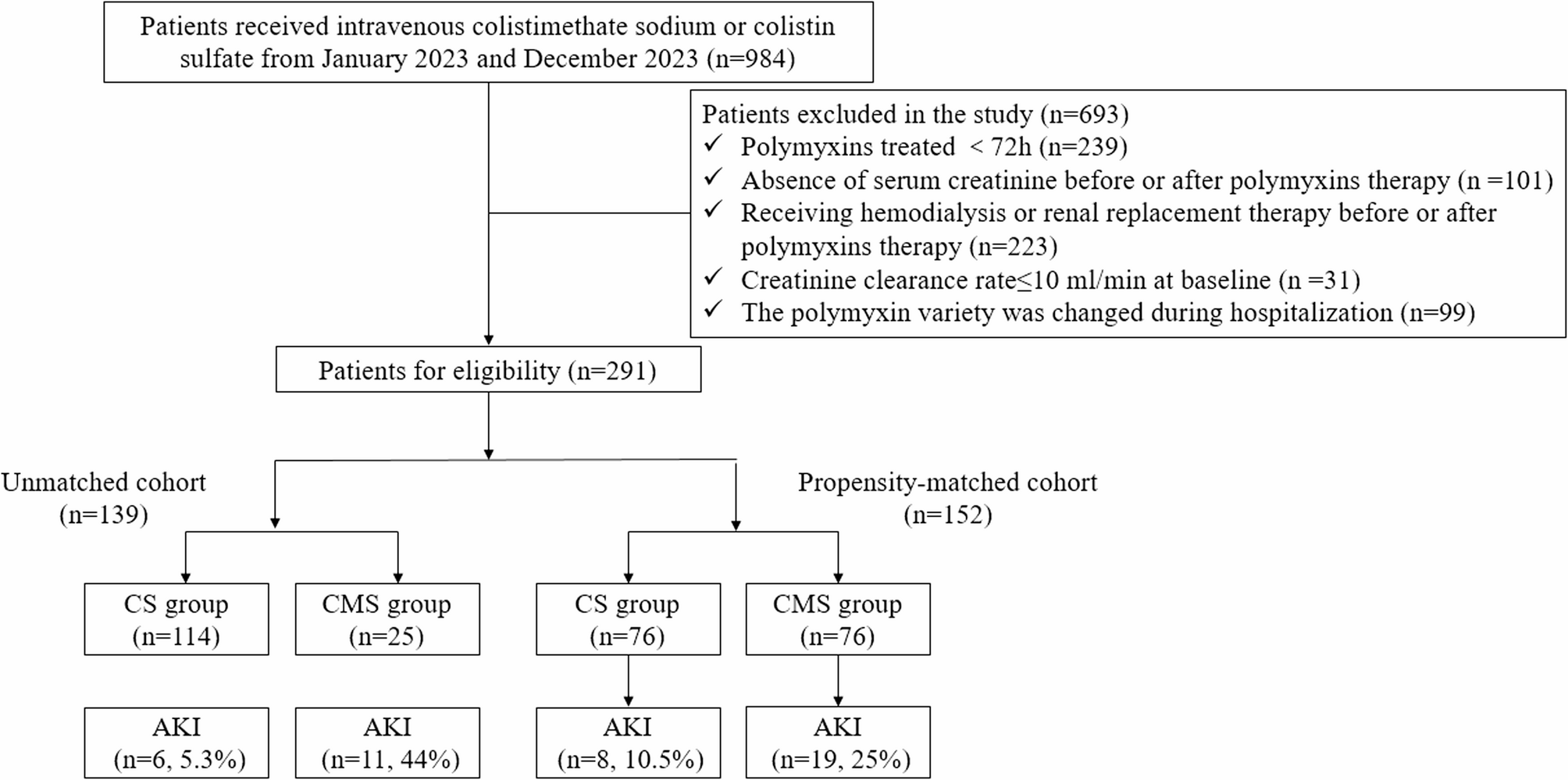

To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate the nephrotoxicity and mortality difference between CS and CMS. The incidence rates of any-stage and stage 3 AKI were significantly lower in the CS cohort than in the CMS cohort. After AKI occurred, 13.64% of patients reduced the dose of polymyxins. 40.91% of patients discontinued polymyxins after developing AKI. 18.18% and 50% of patients demonstrated complete and non-recovery of renal function, respectively.

Past studies have shown that PMB is more toxic to the kidneys than CS. However, the two groups had similar mortality rates [5, 10]. Nevertheless, two retrospective studies found no significant difference between PMB- and CMS-induced AKI [5, 10, 15, 16]. and mortality was similar in patients treated with either agent [6, 9, 17]. To my knowledge, no real-world study has yet compared the nephrotoxicity of CS and CMS. In our studies, the CMS group had a higher incidence of AKI than the CS group, but a lower mortality rate. CMS therapy, along with a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate, was an independent risk factor for AKI. However, AKI occurrence is not a risk factor affecting mortality rate increase by multiple Cox regression analysis.

In the ICU-subgroup, CMS therapy, a lower baseline eGFR and concomitant treatment with ACEI were strongly associated with AKI. However, CMS administration and the combination of hypertension were significantly correlated with the AKI occurrence in the non-ICU subgroup. Multivariate analyses of CMS subgroup revealed that a lower eGFR and concomitant treatment with ACEI were independent risk factors for AKI. Several past clinical studies have associated CMS-induced nephrotoxicity with old age [18, 19], history of chronic kidney disease [19], Charlson score [18], baseline creatinine level [18] and concomitant treatment with vasopressor [19]. In the CS subgroup, multivariate analyses revealed that a lower baseline eGFR was an independent risk factor for AKI. However, CS-induced AKI was associated with advanced age [8, 20,21,22], high serum bilirubin [8], high APACHE II score [22], septic shock [23], diabetes mellitus [22], heart failure [22], higher baseline Scr level [20, 24, 25], low serum albumin [21], blood trough concentration [20], concomitant treatment with other nephrotoxic drugs [8, 21], vasopressors [25, 26], diuretics [25] and inotropes usage [22].

The incidence of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity varied among previous studies. This variability is due to heterogeneous patient populations, different definitions of nephrotoxicity, ranges of doses used, differences in the severity of illness, and the presence of potential confounders such as the concomitant use of other nephrotoxic agents [13]. Most reported nephrotoxicity was mild, and renal function gradually recovered after discontinuation of polymyxins administration [9, 27]. CMS is mainly eliminated by renal excretion, and the urinary excretion involves renal tubular secretion [28]. Colistin and polymyxin B have similar chemical structures and mechanisms of action, exert their therapeutic effect directly and are mainly eliminated through non-renal pathways. Colistin binds to megalin on the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells, triggering its reabsorption into these cells. Intracellular accumulation of colistin causes mitochondrial damage, death receptors activation, and cell apoptosis. Additionally, colistin enhances the permeability of the tubular epithelial cell membrane, leading to the influx of cations, anions, and water, which results in cellular swelling and lysis [29, 30]. Polymyxins are well known to be nephrotoxic to renal tubular cells. It is suggested that the differences in the pharmacokinetics and renal handling mechanisms of polymyxins may lead to higher colistin toxicity than PMB in humans [9]. Published theories have shown that the use of loading doses and the duration of treatment can lead to acute renal injury due to the cumulative effect of the dose [7, 8, 18, 31,32,33]. This has also been associated with higher plasma drug concentrations in some studies [34, 35]. Furthermore, a total dose of colistin > 5 g was an independent predictor of progression to chronic kidney disease [36].

In our study, the overall 30-day all-cause mortality rate was 23.37%, which is lower than in most previous reports on polymyxin drug therapy [5, 6, 9]. Moreover, the 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in the CS cohorts than in the CMS cohorts regardless of propensity matching. The CS group exhibited a higher proportion of hematological system comorbidities, with more severe infection severity. In vitro studies have shown that even at the maximum tolerated systemic dose, PMB cannot achieve effective bactericidal activity. Given the structural similarity between CS and PMB, and that fAUC/MIC is the PK/PD index most closely related to efficacy, it is speculated that CS cannot achieve good bactericidal effects [37]. A systematic review showed that the blood drug concentration in the CS group is lower than that in the CMS group, and the peak time is later than that in the CMS group [38], which is one reasons for the higher mortality rate in the CS group.

In our study, multivariate analyses revealed that CS administration, ICU admission, and a polymyxin loading dose were independent risk factors for 30-day mortality. Unlike previous reports, mortality was associated with polymyxins-induced AKI [5, 8, 18, 19, 22, 24, 25], age [18], septic shock [8, 9], combination with lymphoma malignancy [8], SOFA score [39], extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment [39], hematologic malignancy [8], hypoproteinemia [8], mechanical ventilation [9], presence of a central venous catheter [9], higher baseline creatinine levels [18] and Charlson comorbidity index [9, 18, 19], concomitant use of vasopressors [19]. This may be related to the different patients enrolled and the types of polymyxins used.

However, our study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective study conducted in a single center with a limited sample size, and it included patients from a tertiary hospital. Despite employing propensity matching, there may still be an undisclosed quantity of residual unmeasured confounding and bias present in this observational study. Secondly, drug concentrations of colistin sulfate were not monitored during treatment and the correlation between nephrotoxicity and blood drug concentrations was not investigated. Thirdly, the majority of patients were treated with colistin sulfate alongside other drugs due to polymyxin’s heterogeneous resistance, meaning colistin sulfate may not be solely responsible for the ultimate effectiveness. Furthermore, considering the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of drug use, clinicians may not fully comply with international guidelines when selecting colistin dosing regimens, particularly with regard to loading doses and dosing intervals. This has also caused research bias. This could explain why the results of this study differ from those of previous studies. Therefore, future multicenter, randomized, controlled, prospective trials are needed to better assess the efficacy and safety of colistin sulfate.