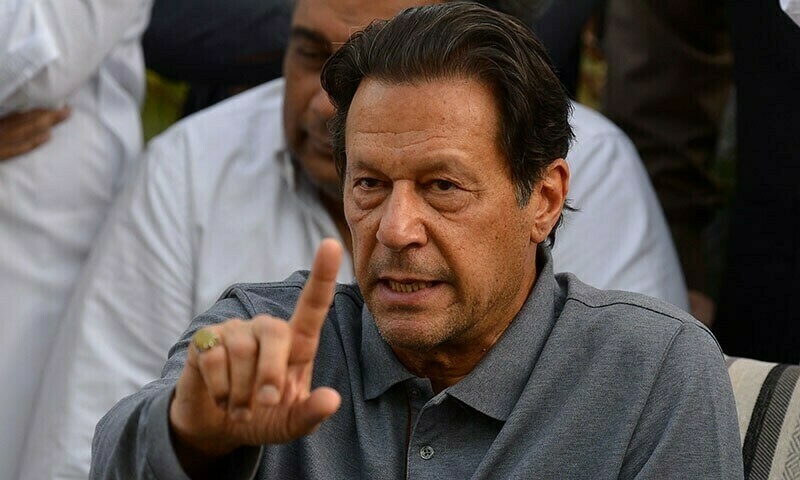

ISLAMABAD: The Supreme Court will resume on Aug 12 the hearing of a set of appeals moved by ex-premier and PTI founding chairman Imran Khan against the denial of bail by the Lahore High Court (LHC) in cases related to the May 9 violence.

A three-judge SC bench, headed by Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Yahya Afridi and including Justice Muhammad Shafi Siddiqui and Justice Miangul Hassan Aurangzeb, will take up the matter on Tuesday.

The apex court had previously adjourned the proceedings due to unavailability of Salman Safdar, senior counsel for the ex-premier.

In his appeals, the incarcerated PTI leader claimed that the LHC on June 24 denied post-arrest bail to him in eight cases related to May 9 violence, including attacks on Askari Tower at Liberty Chowk, PML-N offices in Model Town, Shadman police station, the burning of police vehicles near the Lahore corps commander’s residence and violence at Sherpao Bridge. The appellant said he moved the LHC after an anti-terrorism court had denied bail to him in the eight cases on Nov 27, 2024.

CJP-led bench put off previous proceedings due to unavailability of ex-PM’s lawyer

He said he was accused of conspiring and abetting violence on May 9, whereas, at the time of the alleged offence, he was in the custody of National Accountability Bureau (NAB). Therefore, his involvement in the May 9 violence was “impossible”, the appeal argued, while reminding that the Supreme Court had already held that the case of an abettor who was not present at the scene of occurrence stands on a lower legal footing than that of a principal accused.

According to the set of appeals, the PTI founder had been subjected to an “unprecedented campaign of political victimisation” since his ouster as prime minister in 2022. The SC was informed that the cases were yet another attempt by the state and the police to “implicate” him in a criminal matter, based solely on “vague and unsupported allegations of abetment” as the prosecution had no “convincing” evidence connecting Mr Khan to the alleged offence.

After Mr Khan’s “unlawful and invalid” arrest from the premises of the Islamabad High Court on May 9, 2023, multiple FIRs were registered in Lahore and Islamabad, it contended, adding none of the complaints contained any specific allegations or details regarding the purported conspiracy.

At a later stage in these cases, the prosecution introduced supplementary statements by police officials in an apparent attempt to “falsely implicate” Mr Khan, it added. If, as per the prosecution’s claim, the police allegedly knew about the conspiracy to orchestrate violence as early as May 7, why did they not take any action to prevent the attacks, the appeal questioned. This was “highly illogical” and further exposed the “malafide and politically motivated nature of the proceedings”, it claimed.

The appeal alleged Mr Khan had been “maliciously implicated” in these cases as part of a “calculated and politically motivated design to prolong his incarceration”, harass him and tarnish his public image.

Mr Khan’s arrest was “never genuinely required” in cases pertaining to May 9 violence, it pleaded, adding that police took no action to arrest Mr Khan for over five months even after his bail applications were dismissed by an anti-terrorism court in Lahore. Despite knowing Mr Khan’s whereabouts — Adiala jail where he was confined — the police “made no meaningful attempt to effect his arrest”, it argued.

“This lack of urgency or interest on part of the investigating agency strongly supports the inference that the arrest was not necessitated by the merits of the case, but rather was a tool of oppression, thereby further justifying the grant of post-arrest bail,” the appeal said.

According to the appeal, the LHC decision to deny bail to Mr Khan was based on “engineered and fabricated evidence” comprising stale, discredited, and delayed statements of police officials recorded long after the occurrence, without any plausible explanation for the inordinate delay.

It argued that the LHC while rejecting the bail plea also failed to appreciate that the prosecution has been consistently shifting its stance like a pendulum, by introducing materially improved versions of the case narrative.

Each new version was introduced only after the preceding one failed to withstand before the courts of law, thereby rendering the prosecution’s case doubtful and entitling the petitioner to the benefit of further inquiry, the appeal pleaded. These material contradictions and afterthoughts clearly made out a case falling within the ambit of Section 497(2) of the criminal procedure code, warranting the grant of bail, the SC was requested.

Published in Dawn, August 10th, 2025