Lucy is already well on its way to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. But that doesn’t mean that it can’t make some improvements to its trajectory along the way. A new paper suggests it might be possible to nudge Lucy into a slightly different orbit, allowing it to pass an as-yet-undiscovered asteroid sometime during its exploration of the L5 cloud of Trojan around Jupiter. If completed, it could lend an entirely new research target to Lucy’s repertoire and further define the differences between the two Trojan clouds.

The cloud at L4 is already Lucy’s primary target, with four of the mission’s planned five asteroid visits occurring in that leading grouping. The one exception is the Patroclus-Menoetius binary, which is a large binary in the L5 grouping – the group of asteroids traveling behind the planet on its orbital path. In both groups, Lucy will only be visiting a tiny fraction of the total number of asteroids thought to populate the space.

Lucy’s orbital flight path is…complicated to say the least. It will use several gravitational assists from Earth and the Sun to complete its journey out to Jupiter’s orbit two separate times, and one of the primary goals of the paper was to calculate what would be needed to slightly nudge its orbit to pass by a much smaller asteroid, even if that asteroid hasn’t officially been discovered yet.

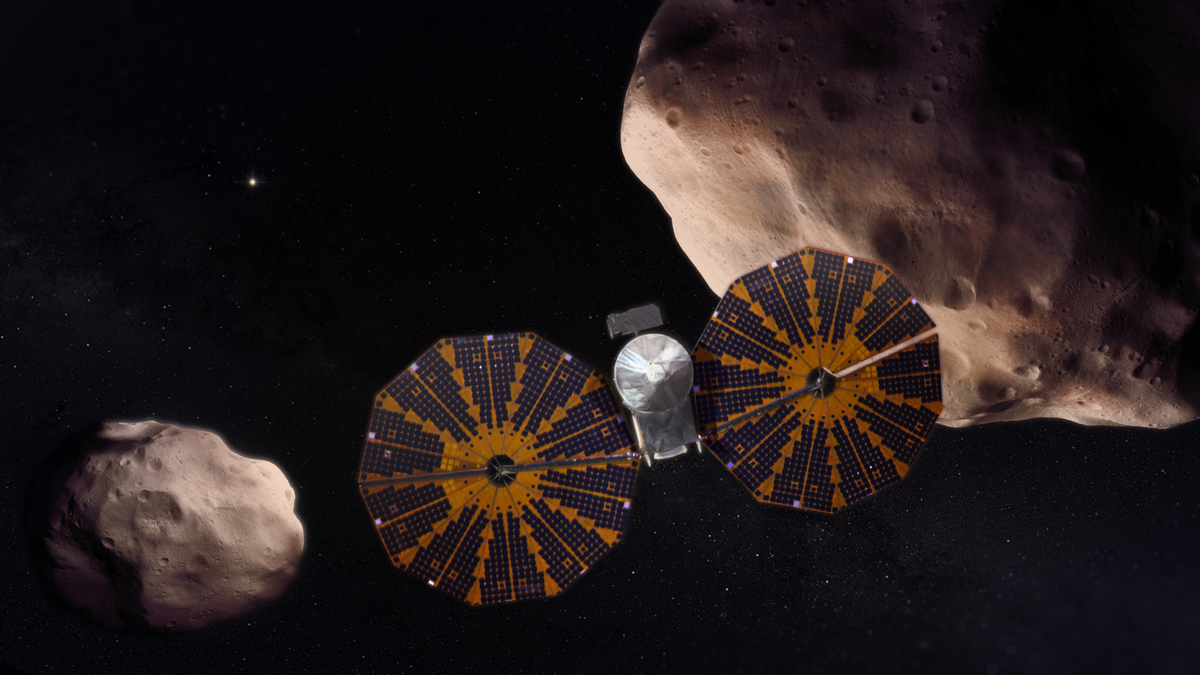

Flight path for Lucy going by both L5 and L4 Trojan clouds. Credit – NASA

The logical first step would be to actually discover what asteroid Lucy would be trying to approach. Most larger asteroids in the L5 group (i.e. those with diameters more than 10km) have already been discovered. However, there are known to be plenty of undiscovered ones that either haven’t had enough observational time or a strong enough observatory pointed at them.

Asteroid diameters are also known to follow a power law, with significantly more asteroids of smaller diameters than those of larger ones. Since we already know the numbers of larger asteroids, the researchers could then make estimates of the total numbers of smaller asteroids in the system. They then modeled the approximate positions using statistical distributions for their latitude, longitude, and heliocentric distance.

Those results were then used to plan an observational timeline in late 2026 when the trojans are in opposition from Earth. According to the paper, if one of the larger telescopes, such as Subaru or the Vera Rubin Observatory, would observe only the area where there is likely the highest density of asteroids, they would likely find potential flyby candidates around 700m in diameter in only one night of observational time. A smaller asteroid of only 500m would take a few nights, and both would require a “stacking” technique that would track faint objects over time. However, if that observational campaign was dedicated to finding another target for Lucy the authors left little doubt it would be able to find one.

Fraser discusses Lucy’s mission and why it is so important for our understanding of asteroids.

But how close would Lucy already have to be to it? Any course correction would take energy, and too much of one could endanger the rest of the mission objects. To make that estimate, first the authors, who include Lucy’s Deputy Principal Investigator and Deputy Project Scientist as well as researchers from various American universities and NASA, had to calculate a maximum amount of “delta-v” that could be used for the purpose of changing the craft’s trajectory. They settled on a “moderate” course correction of around 50 m/s, which is manageable with the fuel reserves Lucy is already carrying.

They also calculated there were two potential times when that delta-v shift might be viable. The spacecraft could adjust its course after its third gravity assist from Earth, which is aimed at angling it towards the center of the L5 cluster. However, if it does adjust course using the gravitational assist, it would still need to course correct after the flyby with the new asteroid to ensure it can still reach its target binary in the L5 cluster. Doing the change during this window has the advantage of being more likely to be able to pass by an asteroid closely, as they are more tightly packed in the center of the L5 cloud, but it has a limited amount of time to make the adjustment.

Another window would be “post-Patroclus”, when the spacecraft is sailing out toward the outer edge of the L5 grouping. This option would allow for a larger volume to be reached with a quick change in velocity and a much longer time window to reach a potential target, even if there are fewer of them to reach.

To execute this plan, the mission team will need to get observational time on a sufficiently large telescope during that end of 2026 window. If they don’t, it isn’t likely they will be able to find an additional asteroid for Lucy to visit. Given the potential new science that could come from visiting an asteroid in that size range, especially with the relatively limited cost of a slight trajectory change to an already operational mission, it would seem a waste to not take that opportunity. But, observational time is in high demand across the board, so for now the asteroid community will just have to wait and see if the intrepid Trojan explorer will be the support it needs to be even more groundbreaking.

Learn More:

L.E. Salazar Manzano – Prospects of a New L5 Trojan Flyby Target for the Lucy Mission

UT – Lucy Sees its Next Target: Asteroid Donaldjohanson

UT – Lucy Adds Another Asteroid to its Flyby List

UT – Lucy Has its First Asteroid Target in the Crosshairs