Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2025.

The US dollar assets and liabilities of euro area banks arise mainly from their capital market activities. Capital market activities are often characterised by short maturities and require daily marking to market and margining. These features may pose a liquidity risk to banks in the event of abrupt market movements. US dollar funding and hedging instruments provided by banks are also important for euro area corporates and non-bank financial institutions, especially when exchange rates move rapidly. This box presents the business rationale for euro area banks’ US dollar activities and aims to assess the associated financial stability risks.

US dollar activities are concentrated among euro area global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), which intermediate US dollars to other European parties. In contrast to other major currencies, US dollar activities relate almost exclusively to wholesale business.[1] The breakdown of euro area banks’ US dollar assets and liabilities reveals the high weight of capital market activities relative to loans and deposits from the non-financial sector (Chart A, panel a). Other financial assets and liabilities, which include primarily the positive fair value of derivatives, are the largest balance sheet position denominated in US dollars. They are followed by repo borrowing, debt securities funding, holdings of debt securities and deposits taken from banks and other financial institutions.

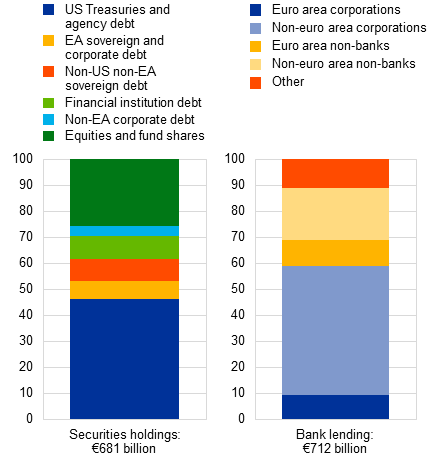

Banks’ dollar-denominated credit exposures are largely limited to holding high-quality debt securities and lending to the non-financial corporate sector. Euro area banks’ debt securities holdings denominated in US dollars consist mainly of US Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities, followed by debt issued by non-US governments and financial institutions. These securities qualify as high-quality liquid assets. Euro area banks’ dollar-denominated lending is estimated to be close to €700 billion at the least (9.2% of the total loan book), with most of this going to non-euro area corporate and non-bank financial clients (Chart A, panel b).[2]

Chart A

Capital markets business dominates in euro area banks’ US dollar activities

|

a) Dollar-denominated assets and liabilities of 48 euro area significant institutions, by bank type |

b) Dollar-denominated securities holdings and bank lending of euro area banks |

|---|---|

|

(Q4 2024, € trillions) |

(Q4 2024, percentages) |

|

Source: ECB (supervisory data, SHS, AnaCredit) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: based on annual funding plan reports by 48 banks, including five global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), for which US dollar-denominated liabilities account for over 5% of their total liabilities. The share of these banks in the total assets of significant institutions supervised by the ECB amounts to 56%. The data on repos use the liquidity coverage ratio template and capture only transactions with a residual maturity up to 30 days, while the data on reverse repo lending to financials use the net stable funding ratio template. “Other financial assets/liabilities” mainly includes trading assets and liabilities such as derivatives, equity and fund shares, and repo borrowing with a residual maturity of more than 30 days. “Other banks” includes, among others, euro area subsidiaries of US banking groups. Panel b: covers all euro area significant institutions, meaning numbers are larger than in panel a. Data exclude subsidiaries of non-euro area banks in the euro area and loans held in the foreign subsidiaries of euro area banking groups. The debt of supranational issuers is included in non-US non-euro area sovereign debt. Lending data are based on the AnaCredit dataset and exclude retail loans to households, loans to banks, reverse repo transactions and intragroup exposures. EA stands for euro area. “Non-banks” refers to non-bank financial intermediation entities.

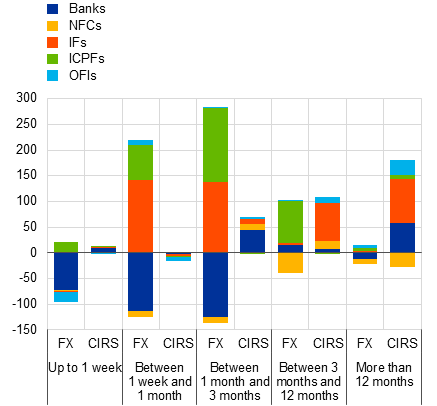

The US dollar activities of euro area banks in capital markets represent a diverse set of financial services to the economy. Euro area banks, especially some of the G-SIBs, are present in US money markets, where they act as intermediaries by sourcing funding from money market funds and lending the proceeds to hedge funds on a secured basis.[3] Euro area investment funds, life insurers and pension funds invest in dollar-denominated assets, despite their euro-denominated obligations to fund-shareholders or policyholders. Euro area banks facilitate these counterparties’ needs to mitigate the resulting currency risk by engaging in FX swaps, effectively receiving US dollars and paying euro to investment funds, insurance corporations and pension funds. Euro area banks partially hedge this currency risk by taking opposite positions with global banks (Chart B, panel a). These US dollar liabilities are not visible on bank balance sheets.[4] Euro area banks also provide currency hedges to euro area exporters and importers, although such hedging trades are on a smaller scale than those associated with euro area financial investors. For instance, as of July 2025, banks are facilitating US dollar payments to non-financial corporations via currency swaps, primarily to stabilise such corporations’ import costs rather than to manage dollar-denominated revenue flows.

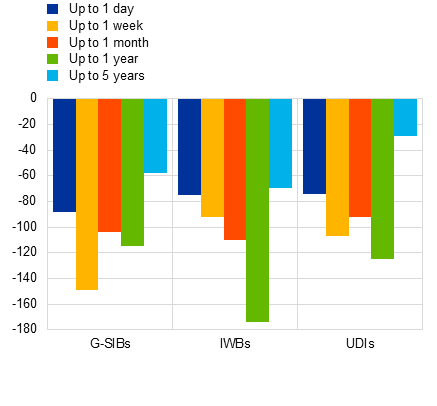

While asset-liability mismatch appears to be limited in extent, banks are nonetheless taking liquidity risk due to mismatches between counterparties providing and receiving funding. Some banks mitigate liquidity risks further by running maturity-matched repo books and do not use volatile short-term repos to fund illiquid long-term assets. However, these strategies do not fully eliminate liquidity risk. While banks hold sizeable quantities of high-quality liquid assets, dollar outflows in an extreme scenario could exhaust their capacity to raise cash through repos, FX swaps and the sale of such assets.[5] The value of liquid assets may also decline in these circumstances, exacerbating liquidity pressures.[6] Although net outflows of US dollars could be covered by US dollar liquid assets in the long term, the net outflows are concentrated in the short term. Some banks may require additional funding in US dollars or rely on inflows of US dollars from maturing short-term assets to remain liquid during financial stress (Chart B, panel b). However, collecting these cash inflows would imply that they reduce US dollar funding to counterparties.

Chart B

Euro area banks’ US dollar intermediation activities

|

a) Euro area banks’ net dollar-denominated FX swap and CIRS positions |

b) Cumulative contractual gap between US dollar inflows and outflows to/from euro area banks |

|---|---|

|

(Q2 2025, € billions) |

(Q4 2024, percentages of US dollar HQLA) |

|

|

Source: ECB (EMIR, sector enrichment based on Lenoci and Letizia*, supervisory data) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: foreign exchange (FX) swap and cross-currency interest rate swap (CIRS) positions of euro area banks with other counterparties, netted within maturity bucket. Within the same maturity bucket, euro area banks’ derivatives positions with the same counterparty sector are netted against each other. A positive net position indicates that the euro area banks are committed to receiving US dollars and paying euro with a specific time bucket. “Banks” includes net derivatives positions with banks that are not supervised by the ECB. NFCs stands for non-financial corporations; IFs stands for investment funds, including money market mutual funds; ICPFs stands for insurance corporations and pension funds; OFIs stands for other financial intermediaries. Panel b: the periods denote the residual maturity of the contractual inflows and outflows. The net contractual gap is calculated as the sum of the net contractual outflows (gross inflows less gross outflows) scheduled over a given horizon and presented as a share of dollar-denominated HQLA. G-SIBs stands for global systemically important banks; IWBs stands for investment and wholesale banks; UDIs stands for universal and diversified institutions, which include universal banks and diversified lenders; HQLA stands for high-quality liquid assets.

*) See Lenoci, F.D. and Letizia, E., “Classifying Counterparty Sector in EMIR Data”, in Consoli, S., Reforgiato Recupero, D. and Saisana, M. (eds.), Data Science for Economics and Finance, Springer, Cham, 2021.

Maintaining adequate balance sheet capacity is necessary to enable banks to act as shock absorbers. If euro area banks reduce their dollar intermediation, their counterparties could face difficulties funding or hedging dollar-denominated investments and may need to sell such assets. Capital and US dollar liquidity buffers provide the balance sheet space required by banks to offer financial services in US dollars to their counterparties in times of financial stress. Capital headroom could be needed to absorb the increase in capital requirements associated with higher currency volatility and counterparty credit risk. Although liquidity risk may not materialise in banks’ own balance sheets and there is no regulatory requirement for banks to match the currencies of liquid assets to the currencies of liabilities, banks should hold liquid US dollar assets to counterbalance outflows and act as a stabilising intermediary.