Artificial intelligence is slowly entering the world of reserve management, but not in the way outsiders might assume. A new report by OMFIF’s Global Public Investor Working Group shows central banks approaching AI with caution shaped by years of market shocks, cybersecurity incidents and the hard lessons of operational risk. Behind the interest lies a simple tension. AI can make reserve management faster and more efficient, but it also expands the attack surface, accelerates market dynamics and exposes institutions to mistakes they cannot afford.

The working group, made up of BNY, Bridgewater and Capital Group, brought together 10 central banks through bilateral exchanges across Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America. Their discussions revealed a pattern that cuts across mandates and regional tensions. The technology is coming, but central banks want control before capability. They are not willing to let algorithms set the pace.

Adoption is happening, but mostly at the edges

Most institutions are experimenting with AI only in low-risk processes: scanning market news, flagging anomalies and summarising reports. According to OMFIF’s Global Public Investor 2025 survey, 61% of central banks say AI is not yet supporting their operations in any meaningful way (Figure 1.1). Those dipping their toes in describe it as a practical convenience rather than a strategic tool.

A European participant of the working group discussions noted that AI can help unclog routine bottlenecks, easing the burden on small teams. Others see potential in automated data processing or environmental, social and governance data screening. AI may accelerate workflows, but it is not allowed near decisions that carry financial, reputational or political consequences.

Figure 1.1. Adoption of AI is limited

How is artificial intelligence supporting your operations? Share of respondents, %

Source: OMFIF Global Public Investor 2025 survey

Those furthest ahead are also the most uneasy

A striking insight from the working group conversations is that the institutions with the most advanced use of AI are also the most concerned about its risks. They understand the potential, but they also see the limitations. Model reliability remains a top worry, especially given how often AI tools misinterpret unusual scenarios. Central banks, whose work revolves around rare but disruptive shocks, have little tolerance for such risks.

Cybersecurity is the bigger fear. One policy-maker warned that a breach involving reserves data would not just be an operational problem but a political one. In their words, prudence is credibility. Central banks are keenly aware that adopting AI without airtight governance could endanger both.

AI may make accelerate crises

One of the most interesting working group exchanges came from a central bank already testing AI-driven analytics in market monitoring. Its concern was not about errors in calm times, but about what happens when markets are stressed. Broader use of AI in trading could accelerate how quickly liquidity disappears, turning crises that once unfolded over days into minutes.

This concern is grounded in how these systems are built. Models trained on comparable datasets often respond in similar ways, which can help steady markets during quiet periods, though it also raises questions about how they might behave when conditions turn volatile. For reserve managers who rely on liquidity to defend currencies or stabilise markets, this poses a profound challenge.

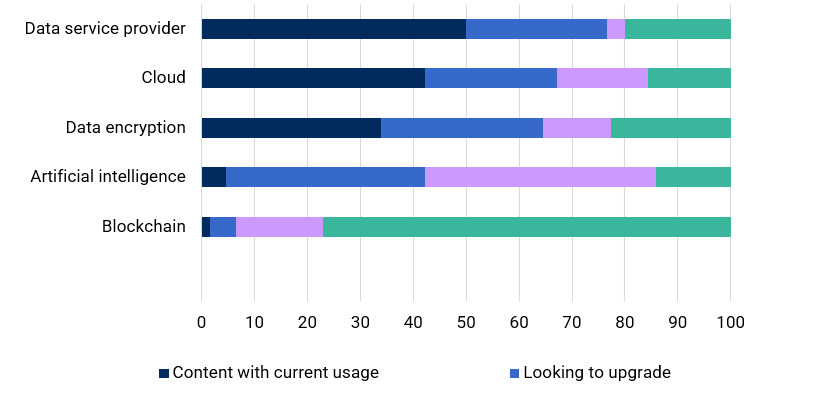

Figure 1.2. Central banks prioritising digital capacity

Are you looking to introduce or expand your use of the following digital technologies? Share of respondents, %

Source: OMFIF GPI 2025 survey

The working group’s conversations showed that the divide between central banks on AI is not about enthusiasm but about capability (Figure 1.2). Some institutions have in-house data scientists and secure enterprise environments. Others have small teams, limited budgets and governance structures that make experimentation slow.

A participant said: ‘We lag, but we cannot lag forever’. For these institutions, AI is less a choice and more an inevitability. But they need training, digital infrastructure and peer support before it becomes safe to bring AI closer to core functions.

The next phase will be about control

Central banks have no interest in outsourcing judgement to machines. The working group report makes clear that human oversight is the anchor. AI can summarise, filter and accelerate, but decisions remain with people.

The question is not whether AI will enter reserve management. The question is how central banks manage the risks it brings. The institutions that move carefully but deliberately by strengthening cybersecurity, investing in skills and building internal capacity will be best placed to employ the technology without being overwhelmed by it.

AI can sharpen decision-making. It can also destabilise markets. Navigating that tension is becoming one of the defining tasks of modern reserve management.

Yara Aziz is Senior Economist at OMFIF.

Download ‘Redefining resilience in reserve management’.

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.