Louis Naidorf, the visionary architect behind the iconic Capitol Records Building, died Wednesday night of natural causes. He was 96. His death was confirmed by his longtime friend Mike Harkins. Naidorf’s distinctive approach to architectural design, blending logic with creativity and function with feeling, helped define the Los Angeles cityscape.

Though best known for the enduring Los Angeles landmark, which opened its doors in 1956 and was officially designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 2006, Naidorf’s legacy spans far beyond the legendary circular tower, which was the world’s first round office building.

His notable body of work includes the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, the now-demolished L.A. Memorial Sports Arena, the Beverly Center, the Beverly Hilton hotel, and the Ronald Reagan State Building. Beyond Los Angeles, he led the six-year restoration of the California State Capitol in Sacramento, and designed the Rancho Mirage residence of former President Gerald Ford and First Lady Betty Ford.

Naidorf’s architectural oeuvre also extends outside California’s borders. He designed Phoenix’s Valley National Bank building (now Chase Tower), the tallest structure in Arizona; and the Hyatt Regency Dallas and its adjacent Reunion Tower, a defining feature of the city’s skyline.

Born Louis Murray Naidorf on Aug. 15, 1928, in Los Angeles, he shaped his future with the same purposefulness and tenacity he brought to his buildings. His parents, Jack and Meriam Naidorf, both worked in the women’s clothing industry and often struggled financially. But young Naidorf, who was already sketching towns by age 8, was too busy dreaming about architecture to notice.

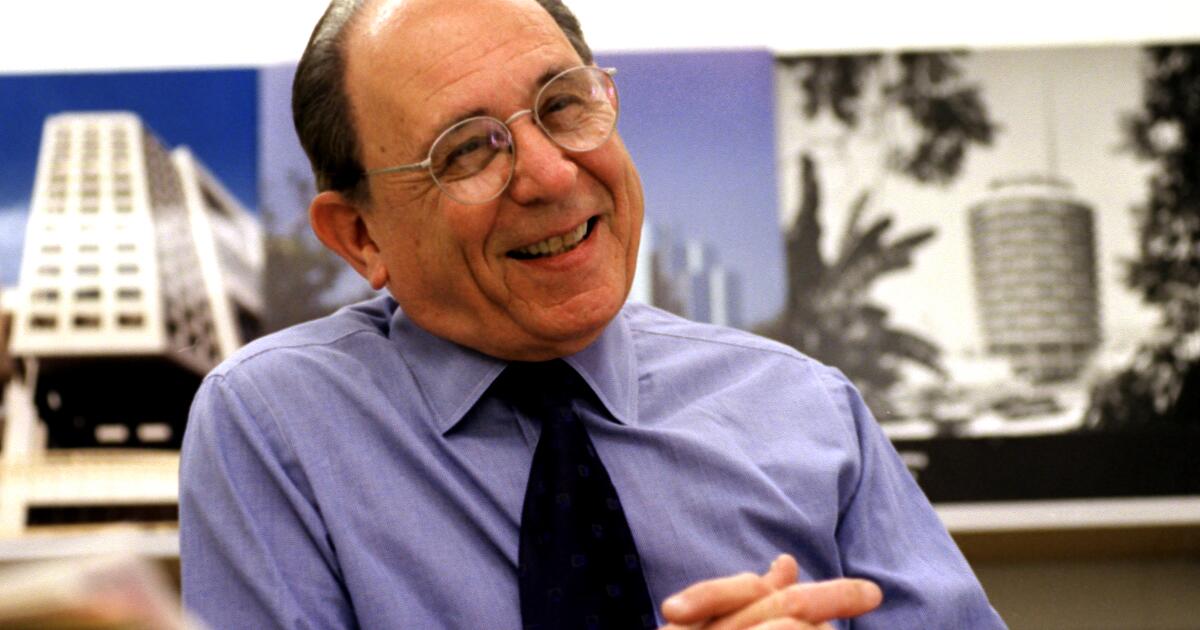

Lou Naidorf in front of the Capitol Records building, one of several Los Angeles landmarks he designed, to illustrate story on his retirement after 10 years as dean of architecture at Woodbury University.

(Al Seib/Los Angeles Times)

At 12, he began collecting architecture books, paying for them with his part-time job earnings. After receiving drafting tools for his 13th birthday, he approached local architect Sanford Kent and asked for a job. Impressed by his initiative, Kent mentored Naidorf, paying him out of pocket.

Naidorf later studied architecture at UC Berkeley. In his 1950 master’s thesis, Naidorf imagined a future in which computers would proliferate and become compact, eliminating the need for sprawling offices. To optimize space, he proposed a bold new concept — circular office buildings — unwittingly foreshadowing what would later become his most iconic project.

After graduating at the top of his class, and earning his master of architecture degree a year early, Naidorf skipped his commencement ceremony to interview at powerhouse architecture firm Welton Becket and Associates. He was hired on the spot.

Aerial drone view of the iconic and historic Capitol Records Building in Hollywood.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Three years later, at 24, he was entrusted with his first major assignment, the mysterious “Project X.” Shrouded in secrecy, Naidorf was given scant information other than the building’s dimensions and location. He had no idea that it would become the headquarters of Capitol Records. Yet struck by parallels between his thesis and the project’s relatively modest size, he applied the round shape to the building. He also aimed to design a “happy building,” both for its inhabitants and passersby.

Throughout his life, Naidorf often refuted the myth that the building was designed to resemble a stack of records. Even so, guided by his core principle of bringing joy to people, he would say, “If it makes people happy to think that, so be it.”

Known for his humor and humility, he would joke that Capitol Records-shaped birthday cakes inevitably collapsed because of a “structural flaw,” playfully suggesting a weakness in the building’s design, and he was endlessly amused by the building’s repeated destruction in disaster movies.

Devoted to mentoring the next generation of architects, Naidorf served as a guest professor at UCLA, USC, Cal Poly Pomona and SCI-Arc. In 1990, he became a full-time academic, starting as chair and later becoming dean of Woodbury University’s School of Architecture, where he earned multiple distinctions, including teacher and faculty member of the year honors.

He encouraged students to be well-rounded and curious about the world so they could connect with future clients on a human level, and to develop unique perspectives that would inform their designs.

Even as he rose to vice president, director of research, and director of design at his firm — and earned numerous honors including the AIA California Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009 — he remained grounded, often saying real life happens outside buildings: sitting at cafés with friends or enjoying a day at the park.

An early photograph of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, another iconic building designed by Naidorf.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Naidorf’s deep humanity, reflected in the title of his now out-of-print 2018 memoir, “More Humane: An Architectural Memoir,” extended to all living things, including doting on his 13-year-old cat, Ziggy Starburst, with whom he shared a birthday — and even small creatures in distress, like a dying bee that he found on his kitchen floor that he carried outside to die, as he put it, “with dignity in nature,” and a snail with a broken shell in his yard that he gently tended to.

A voracious reader, Naidorf was especially fond of science magazines and pondering the cosmos. He also enjoyed classical music. A lifelong traveler, he visited Canada, Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan, and made more than two dozen trips to Europe.

In 2000, drawn by Northern California’s beauty, Naidorf relocated to Santa Rosa, where he worked as a campus architect for Woodbury University and collaborated with City Vision Santa Rosa to enhance the downtown.

Though he retired at 87, he kept his architecture license active, taking his renewal exams every year. Holding the oldest active license in California, issued in 1952, he vowed to be buried as a licensed architect — and so he shall be.

Twice divorced and twice widowed, Naidorf was married four times, and overcame cancer twice. He is survived by his daughter, Victoria, from his first marriage; four stepchildren from his fourth marriage, all of whom called him Dad; 11 grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.